101 Imaginary Nights At The Movies

Tenth in a series of 101 imaginary movies, Cinema of Forgotten Dreams is my attempt to dramatize film history by creating and commenting on a repository of imaginative film viewing. From the earliest days of cinema to the era of blockbusters, my century (plus one) of Movies I Made Up will proceed chronologically through an alternate dimension of films. Will it be allowed? Will anyone read? Though I have no answer to either question, I’m doing it anyway: fortunately, there are no rules in the land of dreams.

cartoonist and animation pioneer Winsor McCay (c. 1867 – 1934)

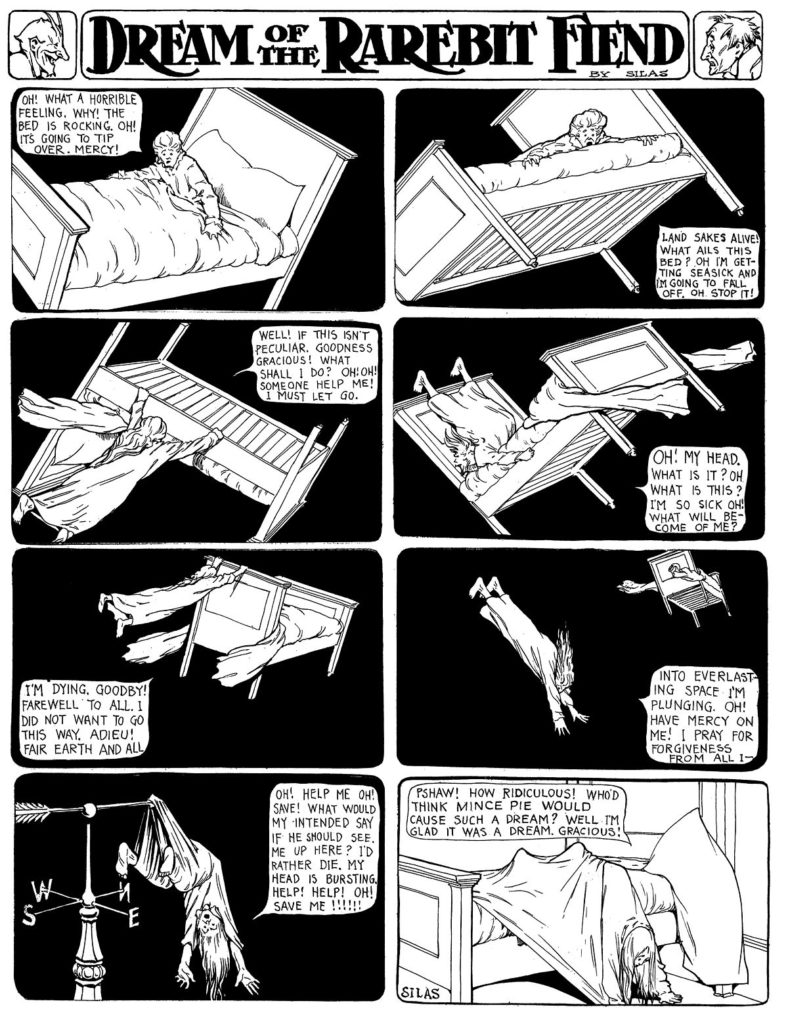

1910 strip of DREAM OF THE RAREBIT FIEND

Rarebit Found

(1910, J. Stuart Blackton[/Winsor McCay])

Animation pioneer Winsor McCay offered this sardonic promotional “recipe” for the New York Phantodrome premiere of a filmed sequel to his comic strip, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend:

Leave bucket of beer on doorstep for neighborhood dogs to lap at on a hot summer afternoon.

Pour remaining contents into boiling vat of very aged (vintage: McKinley administration) cheese.

Add liberal dose of Hungarian mixed spices, complete with crusted remains of grind-miller’s unkempt beard-shavings, just as concoction threatens to explode all over kitchen.

Remove to simmer in the dingiest, dirtiest corner of house.

Flatten two fistfuls of indifferently risen dough into pan-sized shingles, toasting lightly over blue flame until bubbling vaguely congeals into square-ish shape. Wait until no earlier than 9PM, retrieve beer-cheese sauce, and proceed lathering over dough-toast with rusty spoon.

Imbibe with relish – nay, abandon – and surrender to the Welsh Rarebit’s soporific spell.

Dreams of a most unusual character assured.

decidedly more pleasant image of Welsh Rarebit

Accompanied by the vivid image of the strip’s author, signed “Silas the Dreamer”, entering the gooey, twin-sliced mass of this hideous turn-of-the-century repast, which rises up from the dinner table to consume its intended consumer whole, the visual certainly conveys the “unusual character” McCay’s beautifully illustrated excursions into the unconscious afforded early twentieth century Hearst Telegram subscribers.

2007 collection of Winsor McCay’s classic “Saturday” strips of DREAM OF THE RAREBIT FIEND

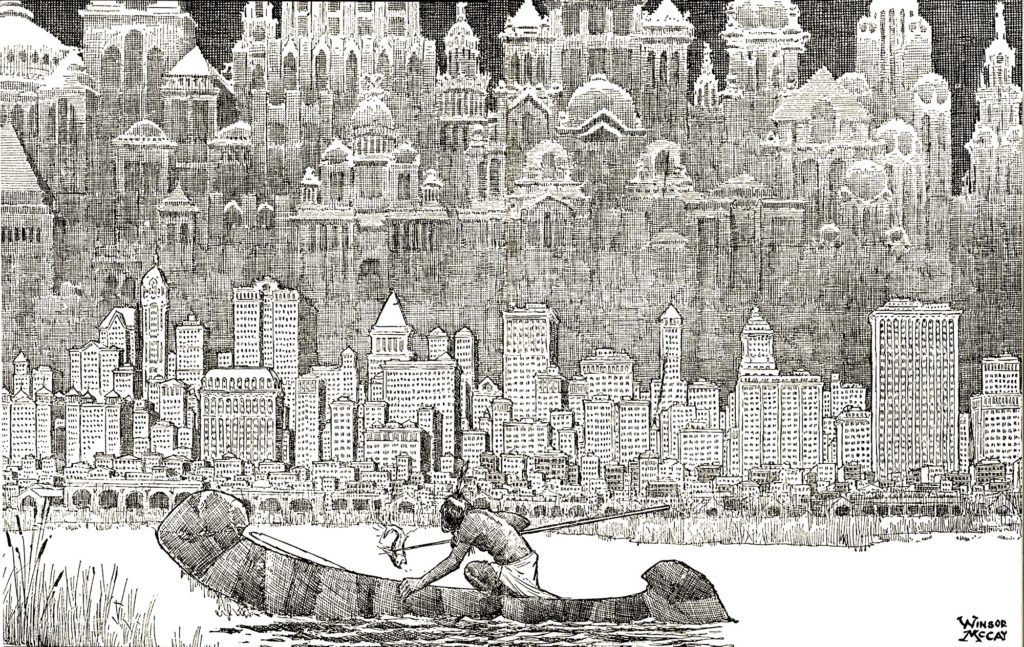

From 1904 through 1913, and opposite its children’s-themed companion strip appearing in the New York Herald — Little Nemo in Slumberland — McCay visualized the wishes, fears, and most of all the irrationalities of its vast readership in exquisitely surreal imagery long before Breton, Dalí, or Buñuel. A man waking on top of the Brooklyn Bridge, the Statue of Liberty climbing down from her pedestal — to ice-skate on the frozen Hudson Bay — a crew of workmen rolling a giant straw hat against the towering height of a skyscraper; these were visionary newspaper panels appearing alongside nightmare scenarios, also vividly realized, of the imaginary near-fatal results of overindulgence: including strips that ended with the dreamer being hung, shot, buried alive, or even falling off the face of the earth…

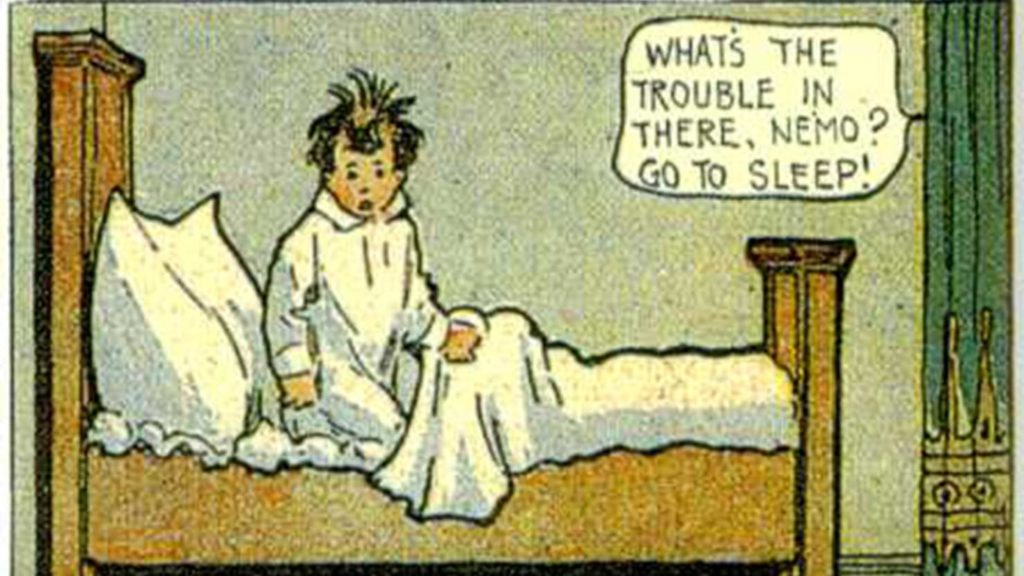

the dreamer awakening (from LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND)

…and of course, waking in a tangle of sheets by the floor of his bed, announcing, “Boy! I’m swearing off that damned Rarebit for good”. Given the intrinsically oneiric subject matter, along with its inherent popularity, Rarebit was a natural for movies, and its first filming, in 1906, produced by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Co., was a hallucinatory delight that still retains much of its after-dinner potency viewed today. (Its movie-dreamer, flying across a city skyline while hanging for dear dream-life off the railings of his bed, in fact provides an overarching image for this entire series.)

Edison Co.’s DREAM OF A RAREBIT FIEND (1906) [credit: MOVIES SILENTLY]

Moving to a better deal with Vitagraph four years later, McCay collaborated with fellow animation pioneer (and company founder) J. Stuart Blackton for the next ten-minute follow-up, resolution, and even conclusion (while the strip was still being published, no less) to McCay’s ptomaine-tinged vision.

unwary, intemperate consumption of rarebit, also from the live-action DREAM OF A RAREBIT FIEND (1906)

Rarebit Found, from 1910, part-documentary and early-animation, defies easy description, but fortunately fits quite well in this continuing rogue’s gallery of forgotten dreams.

Dapper though diminutive Winsor McCay, dressed in slightly oversized coattails, sweeps on stage and removes his silk hat with a flourish, spinning the brim on his outstretched palm and flinging the wobbly lid directly at us, his audience. Directly behind, framing the entire width of the proscenium view, stretches the obsidian reflection, in ebony reversal, of the little man on the big stage. A waving sleight-of-hand reveals a lengthy tube of chalk where McCay’s tar-top formerly lay, and, rolling the drawing instrument across his knuckles, the illustrator spins on his left heel, folding his loose arm behind his back, and, in one motion, sketch-attacks the giant blackboard with the practiced ease of a veteran vaudevillian.

36 seconds of undercranked draughtsmanship follow; the furious back-and-forth between two images rising from the floor gradually reveals the five-foot-high, cartoonist-scaled depiction of a giant ape smoking a cigar leaning against the Woolworth Building. [Eds. Note: Then under construction; completed in 1913.] Imperceptibly, stage and performer vanishing from view, the chalk outlines against the blackboard background now fill the frame, resting on this static cartoon image. A wisping curly-cue of smoke, drifting skyward from the ape’s cigar, signals the viewer’s animated entrance into the Land of Dreams.

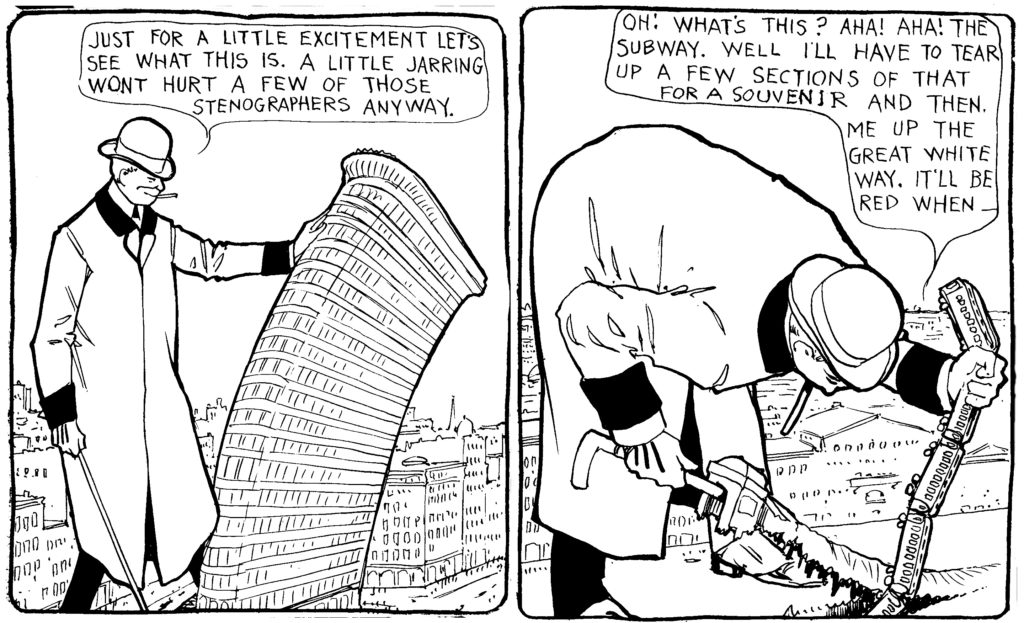

The white-on-black motion-visuals first depicts the gentlemanly simian daintily dropping his stogie ashes over the skeletal steel girders of the half-completed skyscraper. The base of the construction site catches flame, licking the hairy heels of the unwelcome visitor in billowing bursts, and the delicate veneer of the creature’s formerly civilized behavior erupts in a terrifying tantrum of foot-stomping destruction. As the then highest point in the city is reduced to rubble, the fearsome fiend morphs down to size – if not scale – and the familiar form of the strip’s signed author Silas the Dreamer emerges, saluting the viewer with a winsome wink.

Sauntering screen right, over pavement that ends in a grassy meadow, our now fearsome fantasist displays his more thematically-appropriate fiend-tendencies by conjuring up a noontide refection of the strip’s title dish. A long-table visually stretches over the nature scene, and the voracious Silas eagerly seats himself directly under the sun shining its glowing rays upon a bubbling vat of melted cheese, an iron tankard of sepia-shaded ale, and two brightly-buttered slices of toast.

Just as suddenly, the sky darkens, the cheese overflows, the beverage spills, and the toast puffs monstrously into the gaping, waiting, dripping maw of hungry doom. Lightning, torrential rain, and “BOOM!” sound-symbols pour from the formerly idyllic heavens as the overly-yeasty treat swallows poor Silas whole…

…who, with a swirling-dissolve, awakes in live-action as celebrated cartoonist Winsor McCay at his Telegram drawing desk, face downward in a steaming plate of Welsh Rarebit.

a typically virtuosic McCay fantasia; stressing detail, scale, and theme

As much a succession of stream-of-conscious gags as a phantasmagoria of early film tricks and tantalizing transitions, Rarebit Found blurs and erases the boundaries between dreams and reality, fantasy and its fulfilment, and the mind’s eye and chalk’s tip. More than any of his cartoonist contemporaries, McCay whetted the enormous appetite of Telegram and Herald readers for visual delight; but with his first animated films McCay extended the power and scope of that vision towards a sumptuous banquet of pure, unfettered imagination.

“Ambrosia! The food of the gods!”, the final frame of this single-reel informs us. An after-hours snack whose culinary horrors few might contemplate today is nonetheless transformed into the ultimate unattainable; a food grail that can unleash wonders, terrors, and visions alike. But, as the filmed-animated evidence of its “finding” seems to warn, just as long as the Rarebit Fiend doesn’t drown in it.

an unusually dapper Silas wreaking his (un)usual brand of casual destruction