101 Imaginary Nights At The Movies

Eighth in a series of 101 imaginary movies, Cinema of Forgotten Dreams is my attempt to dramatize film history by creating and commenting on a repository of imaginative film viewing. From the earliest days of cinema to the era of blockbusters, my century (plus one) of Movies I Made Up will proceed chronologically through an alternate dimension of films. Will it be allowed? Will anyone read? Though I have no answer to either question, I’m doing it anyway: fortunately, there are no rules in the land of dreams.

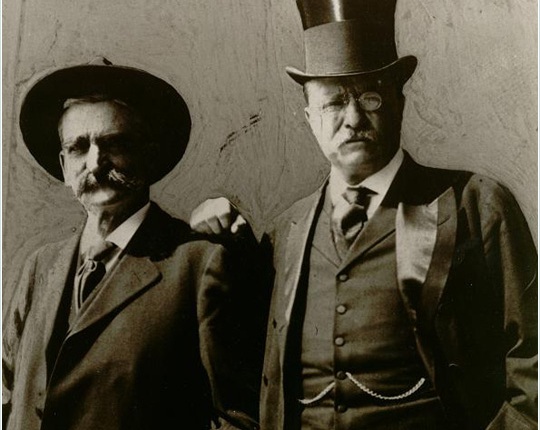

Billy Bitzer (left) and D.W. Griffith (right); 1908

Seth Bullock (left) and Theodore Roosevelt (right); 1908

ROOSEVELT IN THE BADLANDS

(1908, D.W. Griffith)

Possibly the most significant event in early cinema history occurred when the East Coast’s Biograph Company hired failed playwright and actor D.W. Griffith as a crowd and background extra in early 1908. There, shooting films on location in New Jersey, Griffith met film technician and camera pioneer Billy Bitzer and, through a set of converging circumstances, the pair emerged as the first to assume the familiar image of a megaphone-wielding director behind a capable craftsman’s camera. Collaborating on nearly 50 one-reel films in their initial year of production alone, 1908 also saw the filmmaking team’s inaugural foray into popular mythmaking and storytelling legend.

Griffith’s early Biograph days (Bitzer behind camera)

Though the filmmaker’s abiding interest lay in the Civil War era, particularly the period of Reconstruction under which his Kentucky family and forbears suffered greatly, the commercial prospects of such controversial subject matter were then uncertain and, indeed, unproven. As such, his producers suggested a somewhat timelier historical subject for their chief filmmaker eager for the opportunity to make the past live and breathe anew on film. Suggesting The Charge Up San Juan Hill as a possible title and “historical recreation”, Griffith instead recalled the success of The Great Train Robbery (1903) from five years before, connecting that film to a photograph of the later military and political hero he had seen in a newspaper as a boy: particularly, a studio photograph depicting the future US president in the buckskins and fur cap of a frontier hunter.

Theodore Roosevelt; mid-1880s

Subtitled “An Historical Facsimile”, Roosevelt in the Badlands went into production during the final year of the twenty-sixth president’s second term. Anti-corruption legislator, police commissioner, naval diplomat, cavalry hero: Theodore Roosevelt’s career certainly inspired cinematic treatment, though his experiences in the Wild West – particularly the Dakotas of the mid-1880s – were little-known, or at least not as well-remembered, after some thirty years of political Rough Riding. Accordingly, Griffith felt only slightly beholden to actual events: the decision to focus on a little-known episode from the varied exploits of this most adventurous of statesmen stemmed solely from the growing interest in the American frontier just as it was disappearing both geographically and as a way of life.

As Roosevelt in the Badlands would amply demonstrate, a story well-told was of greater value on-screen than slavish attention to the historical record.

stagecoach trail

“On The Trail”

An iris expands from a dusty trail in “Spring 1884”, unveiling the prairie lengths of the recently-completed Medora-Deadwood stagecoach line, which a further intertitle informs us “opened up the Dakotas in an era of growing travel, trade and commerce”. A cloud of dust swirls in front of the stationary camera, a masked figure quickly sweeps past the frame and rapidly rides into the far distance, shooting two pistols into the air all the while. “But the transport and passage of much-needed supplies and goods through the Black Hills also attracted the sinister element known as the Road Agent!”

“Heroic Pursuit”

A close-up reveals the unmistakable downward curl of the future Rough Rider’s hirsute upper lip, which quickly curls upward as he turns to his dour companion. The stiff composure and sober dress of this second man may suggest a backwoods minister but the bright tin star under his jacket, along with the metal-and-ivory curl of doubled-weaponry hanging at his side, equally and unmistakably reveals the companion to be a frontier lawman. Our first buckskins and breeches-clad Westerner raises his long-range rifle in response and points to a distant point further south on the trail. “We’ll head him off at Belle Fourche!” From precisely the same angle and shot-distance that opened the film, with the outlaw riding furiously down the trail, the pursuing pair horse-gallop at a similarly relentless though more measured pace befitting Territorial Law.

“Central Way Station”

[This sequence, along with its immediate aftermath, is missing from current prints of the film, but, following the intertitle, contemporary reviews place the marauding miscreant – identified as one “Crazy Steve” – at Belle Fourche’s crowded stagecoach inn, where he attempts to find refuge, hiding at a back-gaming table with his tattered collar turned upward. Virtually invisible among his loose-living brethren, Roosevelt and the lawman search fruitlessly for their quarry at the bar, dining tables, and games of chance, before a view of a poker player holding black aces-over-eights catches the lawman’s eye. The further visual detail of dust flaking from the player’s boots – lately from the trail – confirms Crazy Steve’s identity.]

“Speak Softly”

[Following the intertitle, a shot – or possibly two – is also missing. Lacking a strict account of its contents, viewers can surmise that our Badlands hero has picked a wooden truncheon from behind the bar – an Irish walking-stick of heavy oak known as a “shillelagh” – and the lawman, having relieved Crazy Steve of the Wells Fargo payroll, grabs the hapless wrongdoer by the scruff of his neck and thrusts him through the door of the inn and out on to the thoroughfare.] Meeting the business end of the future president’s large cudgel upon his egregious egress of the territorial center, Crazy Steve is the “first”, we are informed, to meet the future fate of “monopolies, trusts, and lawlessness”. Leaning under the doorjamb of the inn’s entrance in observance, striking a match against its gnarled and rickety standing-post, the lawman lights his pipe and blows a contemplative smoke ring out onto the prairie breeze.

western saloon

Stopping just short of hagiography, Roosevelt in the Badlands paints a broadly heroic portrait of its title subject, rather focusing on “authentic” details most reflecting the spirit of the era depicted. The dust, dirt, grime, and grit of the Old West – along with its attending hardness, violence, adventure, and masculinity – is on ample display throughout these 11 ½ minutes of undercranked screen action. From the trail’s diminishing point to the visual framing of the “dead man’s hand”, history and legend coincide with just enough accuracy to capture the casual warmth and unspoken friendship between Roosevelt and the laconic lawman, who is almost certainly modeled on Medora deputy sheriff Seth Bullock (1849 – 1919).

frontier lawman Seth Bullock

That spirit is also evident in the collaboration between D.W. Griffith and Billy Bitzer, the camera and its direction capturing the halo glow of the prairie sun off horse-riders’ heads as well as the kerosene-lit interiors of the frontier barroom. The disposition of an upper lip, the curved grasp of a big stick, or the close striking of a match; minor details, yes, but their careful presentation – lighting, staging, framing – brings the audience ever closer to subjects larger than life on screen.

In short, through the spirit of cooperation, Bitzer and Griffith gave a vanished world, that of the American frontier, new life.

Mount Theodore Roosevelt Monument AKA “The Friendship Memorial”; erected by Seth Bullock on the outskirts of Deadwood, South Dakota in July 1919, shortly after the death of the twenty-sixth US president (and shortly before the lawman’s death later that same year)