An Anthology of the Fab Four on the Silver Screen

There are only three artistic entities of which I am I die-hard, life-long fan–all of whom arguably reached the apex of their abilities in the 1960s: Stanley Kubrick, Charles Schulz, and The Beatles.

To talk about the Liverpool boys and their effect on music and, indeed, the world, is daunting. It’s easiest to say they changed everything and leave it at that. Part of this mastery came with their command of the cinematic realm and so, with the new release of Ron Howard’s The Beatles: Eight Days a Week (a chronicle of their touring years largely powered by fan-captured film footage), we at ZekeFilm figured this would provide a shot at surveying the band’s film output from inception to solo efforts and, finally, to post-Beatle scrutiny. Not all of these films feature the Beatles–John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. But all are overseen by their influence as immutable musicians and personalities.

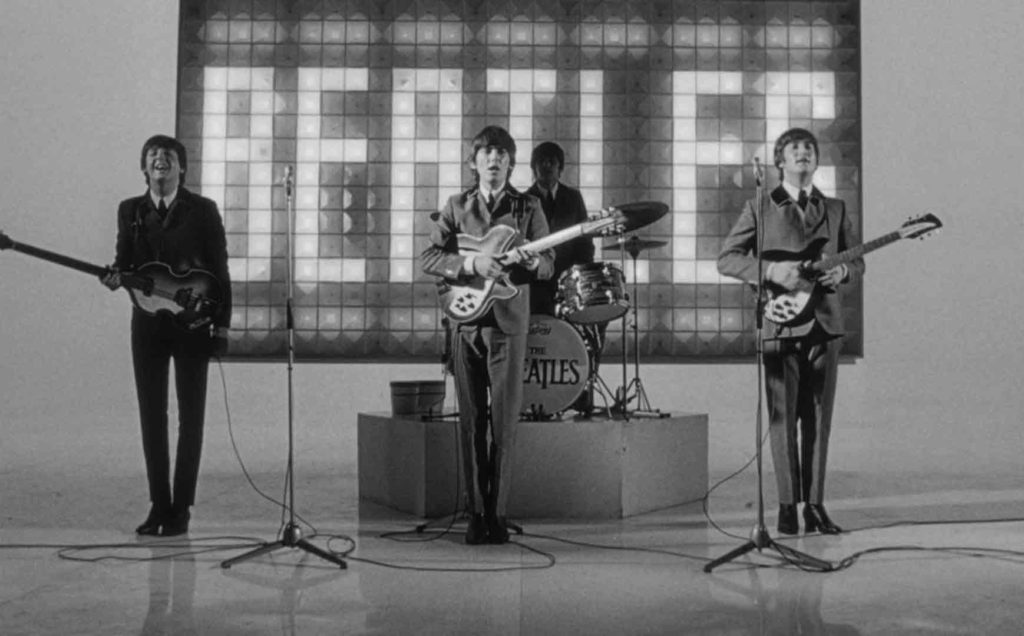

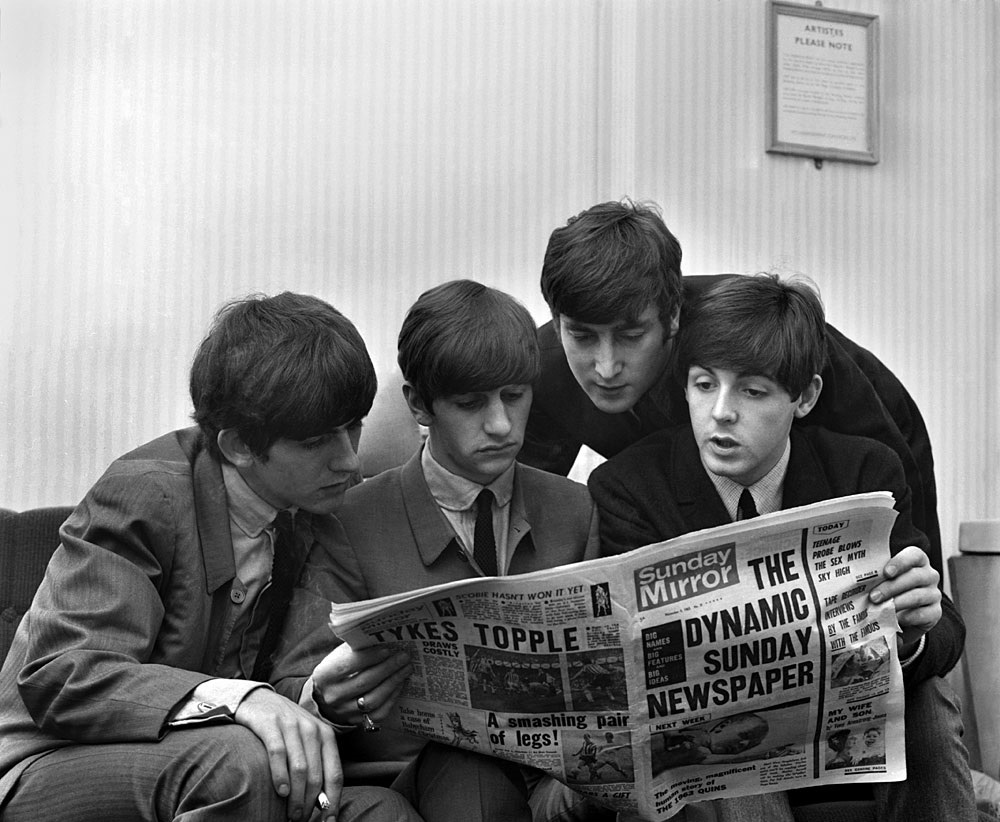

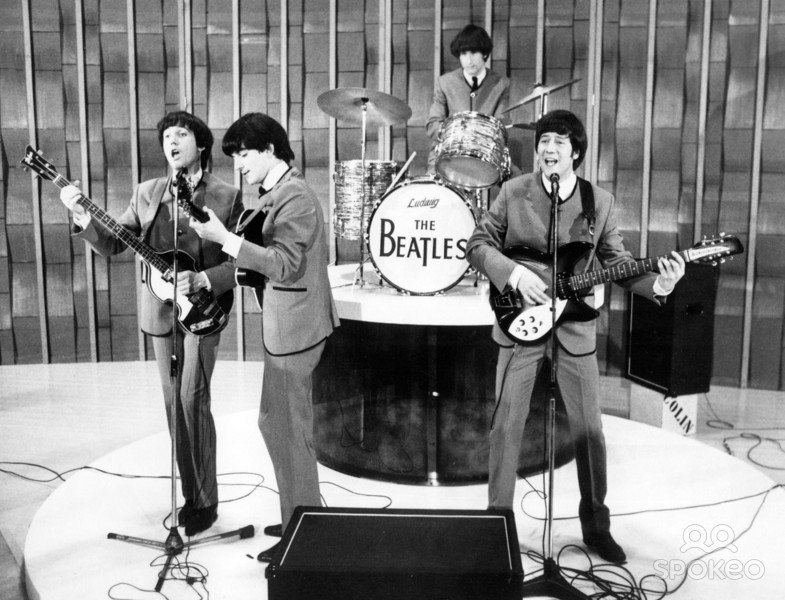

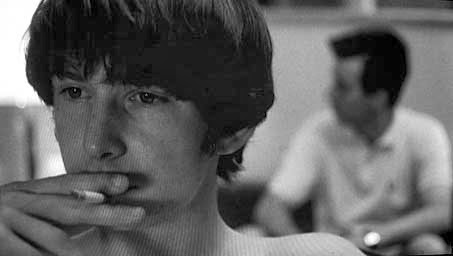

A Hard Day’s Night

(Richard Lester, 1964)  Easily the greatest narrative rock and roll film of all time, A Hard Day’s Night benefits from a perfect match-up of writer (Alun Owen, whose script was nominated for an Academy Award–even now, an unheard-of honor for a film of this type), director (the gifted Richard Lester, an American transplanted to the UK), and stars. Ostensibly a frantic day-in-the-life tale of the Fab Four at the height of their fame, it finds the four walking a gauntlet of screaming fans, snotty handlers, smitten reporters, irritated detractors, and one very clean old man (UK TV star Wilfred Brambell, playing Paul’s mischievous grandfather). Hilarious and incredibly energetic from the get-go, starting with the often-spoofed opening sequence with The Beatles running for their lives as their frantic fandom close in (set to the unforgettable, Ringo-inspired title song) and continuing onto a train, where their hysterical attempts to irritate a stodgy bloke sharing their compartment are among the film’s many highlights.

Easily the greatest narrative rock and roll film of all time, A Hard Day’s Night benefits from a perfect match-up of writer (Alun Owen, whose script was nominated for an Academy Award–even now, an unheard-of honor for a film of this type), director (the gifted Richard Lester, an American transplanted to the UK), and stars. Ostensibly a frantic day-in-the-life tale of the Fab Four at the height of their fame, it finds the four walking a gauntlet of screaming fans, snotty handlers, smitten reporters, irritated detractors, and one very clean old man (UK TV star Wilfred Brambell, playing Paul’s mischievous grandfather). Hilarious and incredibly energetic from the get-go, starting with the often-spoofed opening sequence with The Beatles running for their lives as their frantic fandom close in (set to the unforgettable, Ringo-inspired title song) and continuing onto a train, where their hysterical attempts to irritate a stodgy bloke sharing their compartment are among the film’s many highlights.

Easily the greatest narrative rock and roll film of all time, A Hard Day’s Night benefits from a perfect match-up of writer, director and stars.

Other bright spots, in a virtual sea of them include: Ringo’s pathetic and moving attempts to make human connections while poutily wandering off on his own (his visit to a pub, which he dutifully destroys, is classic, while his short-lived friendship with a young boy is the film’s most lovely moment); John’s wily manipulation of managerial dunderheads Norman Rossington and Victor Spinetti, including one stupendous gag involving John in a sudsy bathtub; George’s stumbling into a fashion designer’s offices, where he’s mistaken for a model and, in one of my favorite lines in the film, is seen as a possible “early clue to the new direction”; and Paul’s increasingly difficult management of his grandfather, particularly at a posh baccarat table (Brambell does his best to steal every scene he’s in). A Hard Day’s Night is a steamroller of sight gags, witty banter, groundbreaking editing, lush photography, and wild stamina (the Beatles romp on an airstrip, running and smashing into each other, to “Can’t Buy Me Love,” is another unforgettable sequence). Impossible not to adore, with terrific performances for all four Beatles, this movie finally transformed the way rock and roll was seen on camera, and by the world (Lester’s effusive capture of the band’s fans in erotic fervor are also a highlight). Songs include: “A Hard Day’s Night,” “I Wanna Be Your Man,” “I Should Have Known Better” (sung to a group of girls on the train–including big-eyed blonde Patti Boyd, who would go on to marry Mr. Harrison), “Don’t Bother Me,” “All My Loving,” the gorgeous “If I Fell” (sung at as TV run-through, right before the group’s about to perform on an Ed Sullivan-like variety revue), “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “And I Love Her,” “Tell Me Why,” “She Loves You.” The real Fifth Beatle, producer George Martin provides an Oscar-nominated adaptation of many of the Beatles’ tunes, including a plaintive version of “This Boy,” employed as Ringo’s walking-around music.

What’s Happening! The Beatles in the U.S.A.

(Albert and David Maysles, 1964)

Documentary filmmakers David and Albert Maysles seemed to be everywhere anything of note was happening in the ’60s, and so they were granted intimate access to the Beatles as they arrived on U.S. shores. Focused on their frantic arrival at Kennedy airport, their hotel room antics and quick-minded press conferences, and their ratings-busting Ed Sullivan show appearance, this is the premier document of the Beatles’ instant mass acceptance as an incipient salve treating a country recently wounded by the violent death of an adored president. As are all of the Maysles’ films, this is essential viewing.

Help!

(Richard Lester, 1965)

Not as good as their first go-round, but still absolutely entertaining, Help! follows the boys as they’re pursued by religious cultists out to retrieve a sacred ring that’s found its way onto Ringo’s fingers (Ringo remains a superb comic here). With Leo McKern and Eleanor Bron as the nominal villains, Lester’s film loses moxie when it conforming to imposed plot demands, but the colors are vibrant, there are some fine jocular moments (including the opening where the Beatles relax in their massive, conjoined flats), and of course, the music is superb. Songs include: “Help!,” “You’re Gonna Lose That Girl,” “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away” (my favorite sequence in the film, glowingly shot by cinematography David Watkin), “Ticket to Ride” (this film’s equivalent to the airstrip stampede in A Hard Day’s Night, this time taking place in the snowy Alps), “I Need You,” “The Night Before,” “She’s a Woman,” and “Another Girl.“

The Beatles

(Al Brodax, 1965-69)

This cartoon series, launched by King Feature Syndicate and animator/producer Al Brodax in 1965, may not be the most swiftly produced bit of animation out there (in fact, it’s often disjointedly stiff), but the charms still comes through in its recognition of the group’s appeal to even the youngest of fans. Over the course of 48 20-minute episodes, scads of songs are heard (usually two an episode), and it can be implicated as the progenitor of the MTV video days, and certainly an influence on The Monkees who, in ’66, would stake their own claims to the charts and airwaves.

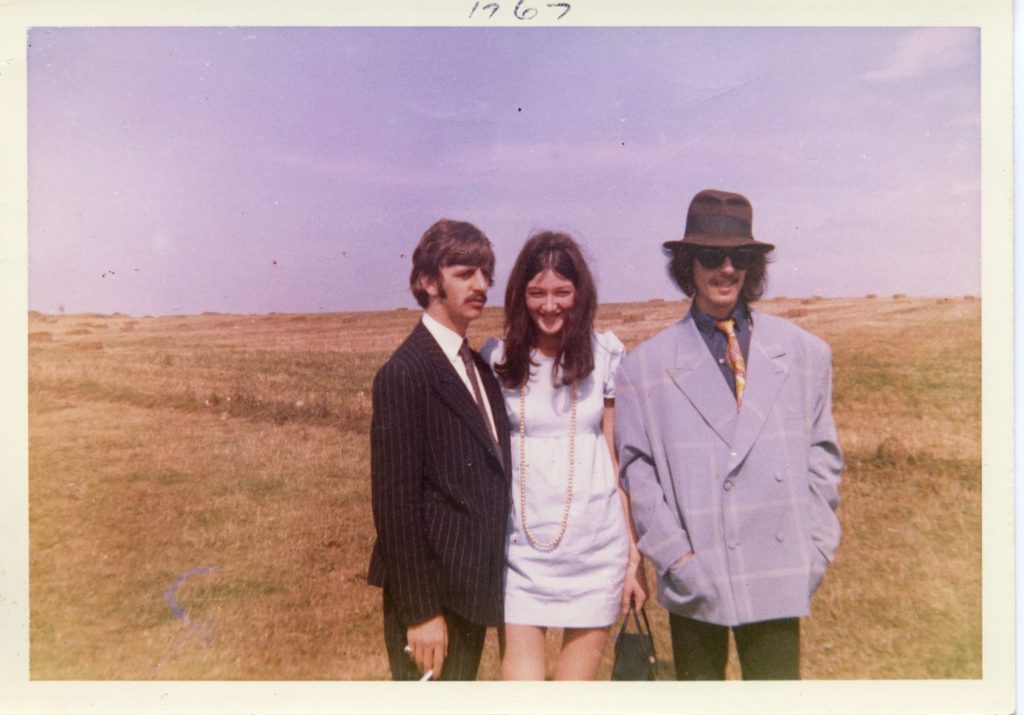

Magical Mystery Tour

(Bernard Knowles and The Beatles, 1967)

Launched after the untimely death of their manager Brian Epstein (he protested the very idea of its production), Magical Mystery Tour is an ugly mess, and largely seen as the first, and maybe the only, chink in their armor (apparently, it was all Paul’s idea). A somehow chintzy-looking hodgepodge of slipshod improv scenes, with The Beatles conducting a packed bus tour of the English countryside, it’s clearly the result of a lot of marijuana and LSD (wait ’til you see John Lennon eating spaghetti with a shovel–pretty revolting). One can easily see why Epstein thought it would be a disaster. Still, there are notable moments, chief among them the wonderfully bizarre sequence with The Beatles dressed in animal costumes while performing “I Am The Walrus.” Other songs include “Magical Mystery Tour,” “The Fool on the Hill,” “Flying,” “Your Mother Should Know” (another good sequence, with the Beatles dressed up in tuxes), and “Blue Jay Way.”

How I Won the War

(Richard Lester, 1967)

In ’67, John Lennon here struck out on his own in his only non-musical role as a musketeer in a troop of misbegotten World War II infantrymen. An episodic anti-war black comedy released as a commentary on the essential ridiculous bloodiness of combat (and of the questionable Vietnam war), Lester’s film has his inimitable snippiness about it, but it’s obtusely tough going. Yet Lennon, in a relatively small role, is as fine as are his cast mates, including Michael Crawford (the stage’s original Phantom of the Opera and star of Lester’s much better Mod London farce The Knack and How to Get It), Michael Hordern (the narrator of Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon), portly Roy Kinnear, and shambling Jack McGowran.

Wonderwall

(Joe Massot, 1968)

Although Paul McCartney is credited with doing the first solo Beatle film scoring work with the Haley Mills vehicle The Family Way, rumor has it that George Martin really polished that job off, so we give the nod to George Harrison. Another druggy curiosity, this little-seen experiment has Jack McGowran as a weirdo scientist who falls for his gorgeous next-door neighbor, a model named Penny Lane (Jane Birkin). With sets designed by The Fool, the Dutch design team that overtook the Beatles’ Apple headquarters during the latter part of the ’60s, and an unusual, instrumental soundtrack by Harrison in his first solo work, Wonderwall is not an easy watch, but if you’re up for some kaleidoscopic oddness, this is the one for you.

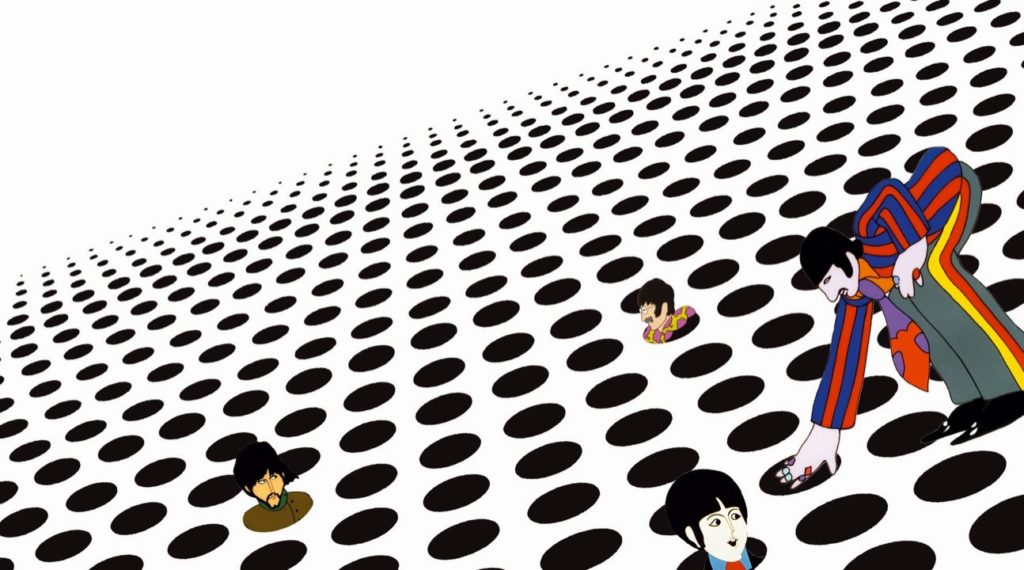

Yellow Submarine

(George Dunning, 1968)

Though their involvement was minimal–they didn’t even provide the voices for their characters–The Beatles finally return to tackling a masterpiece with this surely charming animated film that gives a Peter Max-inspired look to a fantasy world called Pepperland, whose carefree happiness is threatened by the Blue Meanies, a poofy azure band of sneering villains. The Beatles are introduced one-by-one, with Ringo naturally coming first, depressed and alone, and then progressively being joined by prankster John, universally adored Paul, and the loftily spiritual George, who all embark–along with rhyming philosopher thing Jeremy Hillary Boob, Ph.D–in their Yellow Submarine to free Pepperland from the Meanies’ grip.

The Beatles finally return to tackling a masterpiece with this surely charming animated film that gives a Peter Max-inspired look to a fantasy world called Pepperland.

In a major coup, John Clive (as John), Peter Batten (as George), Paul Angelis (as Ringo) and Geoffrey Hughes (as Paul) all convince us that we’re listening to The Beatles proper, which is remarkable unto itself. The film’s endless appeal can also be chalked up to its sure-footed design, yes, but also to its clever, pun-filled screenplay, spearheaded by The Beatles cartoon producer Al Brodax, Lee Minoff, Jack Mendelsohn and Love Story novelist Erich Segal. Songs include “Yellow Submarine” (of course), “Eleanor Rigby” (beautifully rendered in a style that must have influenced Monty Python animator Terry Gilliam), “Love You To,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (adorned with excellent rotoscoped animation–a possible goose to the later work of Ralph Bakshi), “All You Need is Love,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band,” “When I’m Sixty-Four,” “Hey Bulldog” (in a sequence originally cut but later restored), “It’s All Too Much,” “Only a Northern Song” (extremely trippy), and an stirring rendition of “Nowhere Man,” sung as an ode to Jeremy the Boob in the one sequence that always gets me weeping with sheer joy. With a lavish orchestral score by George Martin, this is one of the essentials!

Let It Be

(Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 1970) Long unavailable on digital or even VHS, this revealing behind-the-scenes look at the making of an album meant to get The Beatles back to where they once belonged turned out to be a nightmare and certainly a prime hot-point for the band’s break-up (the film was finally released right around the time they announced their dissolution). We acutely feel the tension in the studio as Paul imperiously dictates the Beatles’ musical performances, with George clearly frustrated by it all, John distracted by the constant presence of his beloved Yoko, and Ringo just sitting there smoking and waiting for the storms to subside. The film luckily ends on a high point, with their final 20 January 1969 rooftop concert over the streets of London (with that other Fifth Beatle, Billy Preston, on keyboards), but the film–while riveting–is a difficult sit, simply because we know this downer is their unfortunate denouement. At any rate, The Beatles won their only Oscars for this film’s soundtrack after a decade of being ignored by the Academy, and so at least that accolade stands as a happy ending. Songs include “Let It Be,” “Two of Us,” “Dig A Pony,” “Get Back,” “Across the Universe,” “I Me Mine,” “Beseme Mucho,” “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “One After 909,” “For You Blue,” “The Long and Winding Road,” and the astounding “Don’t Let Me Down” (which I still think should have been determined the Best Original Song winner of 1969). One thing’s for sure: these guys definitely passed the audition.

Long unavailable on digital or even VHS, this revealing behind-the-scenes look at the making of an album meant to get The Beatles back to where they once belonged turned out to be a nightmare and certainly a prime hot-point for the band’s break-up (the film was finally released right around the time they announced their dissolution). We acutely feel the tension in the studio as Paul imperiously dictates the Beatles’ musical performances, with George clearly frustrated by it all, John distracted by the constant presence of his beloved Yoko, and Ringo just sitting there smoking and waiting for the storms to subside. The film luckily ends on a high point, with their final 20 January 1969 rooftop concert over the streets of London (with that other Fifth Beatle, Billy Preston, on keyboards), but the film–while riveting–is a difficult sit, simply because we know this downer is their unfortunate denouement. At any rate, The Beatles won their only Oscars for this film’s soundtrack after a decade of being ignored by the Academy, and so at least that accolade stands as a happy ending. Songs include “Let It Be,” “Two of Us,” “Dig A Pony,” “Get Back,” “Across the Universe,” “I Me Mine,” “Beseme Mucho,” “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “One After 909,” “For You Blue,” “The Long and Winding Road,” and the astounding “Don’t Let Me Down” (which I still think should have been determined the Best Original Song winner of 1969). One thing’s for sure: these guys definitely passed the audition.

The Concert for Bangladesh

(Saul Swimmer, 1972)  Sloppily filmed, but with landmark live performances, Harrison’s two 1971 concerts benefiting the disaster-ravaged population of Bangladesh resulted in a lineup that included Ringo, Apple-label stars Badfinger (barely seen on camera), Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Ravi Shankar, Billy Preston, producer Phil Spector, longtime Beatles associate Klaus Voormann (the artist responsible for the Revolver album cover), and drummer Jim Keltner. Perhaps better as a recording than as a film (it landed the Album of the Year citation from the 1972 Grammys), yet still fascinating if only to see the normally shy George step out into the spotlight he deserved (and to see the band of friends that rallied to his side). Harrison songs include “Something,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “Here Comes The Sun,” “Wah-Wah,” “Bangladesh,” “Beware of Darkness,” “My Sweet Lord,” and “Awaiting on You All.”

Sloppily filmed, but with landmark live performances, Harrison’s two 1971 concerts benefiting the disaster-ravaged population of Bangladesh resulted in a lineup that included Ringo, Apple-label stars Badfinger (barely seen on camera), Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Ravi Shankar, Billy Preston, producer Phil Spector, longtime Beatles associate Klaus Voormann (the artist responsible for the Revolver album cover), and drummer Jim Keltner. Perhaps better as a recording than as a film (it landed the Album of the Year citation from the 1972 Grammys), yet still fascinating if only to see the normally shy George step out into the spotlight he deserved (and to see the band of friends that rallied to his side). Harrison songs include “Something,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “Here Comes The Sun,” “Wah-Wah,” “Bangladesh,” “Beware of Darkness,” “My Sweet Lord,” and “Awaiting on You All.”

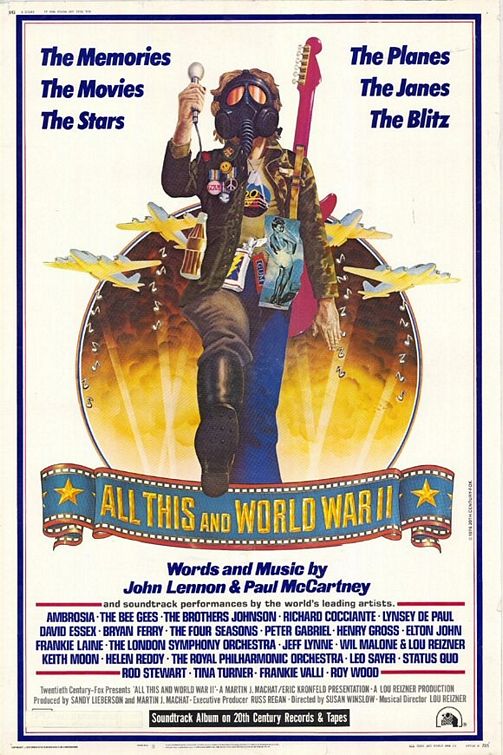

All This and World War II

(Susan Winslow, 1976)

A patently bizarre tribute to the band, this misguided amalgamation of World War II-era battle footage is backed by a motley collection of ’70s stars covering Beatles hits. The one smash that came from this package is Elton John’s respectable version (assisted by Lennon’s backing vocals) of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

A patently bizarre tribute to the band, this misguided amalgamation of World War II-era battle footage is backed by a motley collection of ’70s stars covering Beatles hits. The one smash that came from this package is Elton John’s respectable version (assisted by Lennon’s backing vocals) of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Other curiosities include a high-pitched Peter Gabriel doing “Strawberry Fields Forever,” The Who’s Keith Moon with a suitably distinctive version of “When I’m Sixty Four,” Bryan Ferry assaying “She’s Leaving Home,” false disco god Leo Sayer massacring “I Am The Walrus” and “Let It Be,” ELO frontman Jeff Lynne contributing a credible “With a Little Help from My Friends” and “Nowhere Man,” Helen Reddy with her dull “The Fool on the Hill,” The Four Seasons hitting “We Can Work It Out” (not bad), Ambrosia’s lulling “Magical Mystery Tour,” The Bee Gees portending their future with “Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight,” and Tina Turner soulfully belting out “Come Together.” Not all the performances are terrible–though some, like Ron Wood’s “Polythene Pam,” are absolutely abysmal–but why the WWII connection? I can only surmise this was a cheap way to put visuals to this shipwrecked project which has now justly faded from memory for all but the most devoted.

The Rutles: All You Need is Cash

(Eric Idle and Gary Weis, 1978)

Fueled by the brightly spoofing music of Neil Innes (once a member of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, signed to the Apple label), this Monty Python-flavored bit of wackiness is the best movie the Beatles never made (although Harrison, beginning his long association with the Pythons here, contributes a generous cameo). This immensely funny film–a gut-buster for die-hard Beatles fans especially–has co-director Eric Idle taking us through a decade-long tour with the Rutles–Dirk McQuickly (Idle), Ron Nasty (Innes), Stig O’Hara (Ricky Fataar–a South African in the Harrison role), and Barry Womble (John Halsey)–from their first shows at The Rat’s Nest all the way to their final album Let It Rot. Equally inspired by the success of the then-new Saturday Night Live (for which co-director Weis regularly contributed films), there are cameos by John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, Lorne Michaels, Tom Davis and Al Franken, plus Mick and Bianca Jagger, Paul Simon, Ron Wood, and Idle’s fellow Python Michael Palin. Innes’s songs–all of them targeting specific Beatles hits–include “Hold My Hand,” “Ouch!,” “Number One,” “I Must Be In Love,” “Yellow Submarine Sandwich,” “Love Life,” “Living in Hope,” “Nevertheless,” “Doubleback Alley,” “Cheese and Onions,” “Let’s Be Natural,” “Goose-Step Mama,” “Get Up and Go,” “Baby Let Me Be,” and the amazing ditty “You Need Feet,” which, in parodying the experimental films made by Lennon and Ono, is a particularly delicious jest.

I Wanna Hold Your Hand

(Robert Zemeckis, 1978)

Very possibly the best Beatles movie the Beatles had absolutely nothing to do with (though their music and images are slyly used), this positively chaotic lark follows a carload of Jersey kids as they make their way to the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York City in order to scam a way into seeing the big shoo. Wendy Jo Sperber is a hoot as the most rabid of the girls (the scene where she jumps out of a car to answer a radio trivia question always makes me quake with laughter), while Eddie Deezen is perfect as the goofy, adenoidal superfan with whom she forges an irksome bond at the Plaza Hotel. Nancy Allen is sweet and very sexy as the non-fan who unwittingly gets caught rooting around in the Beatles’ hotel room (in a surprisingly erotic interlude) and Bobby DiCiccio is manically hilarious as a smart-assed Beatles hater along for the ride. Rounding out this superb ensemble, Marc McClure shambles shyly as the team’s love-addled driver, Teresa Saldana is a pip as a girl trying anything she can to get into the show, and Susan Kendall Newman is shakily memorable as a folkie protesting the Beatles’ overtake of the music scene. The freight-train script is written by Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis, making their screenwriting and directorial debuts here in this film produced by Steven Spielberg! By the time we get to the climax (with Will Jordan doing his spot-on Sullivan impression), we’re treated to director Zemeckis’ clever masking the Beatles’ non-involvement by showing their Sullivan performance on television and camera monitors. By this point, we’re nearly exhausted with joyous howls. Don’t miss this one!

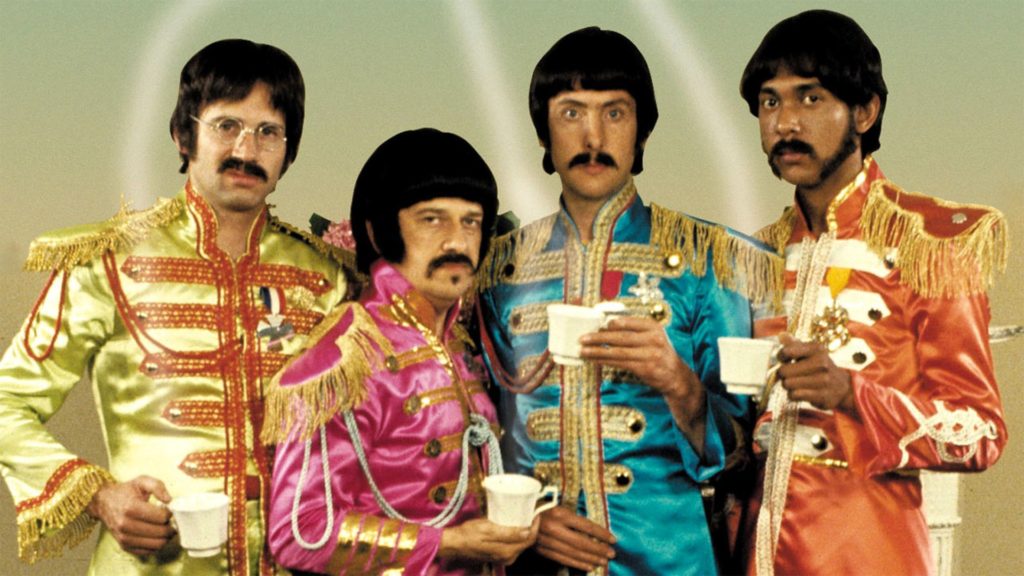

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

(Michael Schultz, 1978)

Infamously awful, this misbegotten interpretation of the Beatles world has Peter Frampton and The Bee Gees playing the titular band and thereby insuring their future near-disappearance from the cinematic landscape (luckily, the Bee Gees were still sailing from their Saturday Night Fever success). Produced by Robert Stigwood, who’d once almost gotten the Beatles in his managerial mitts (he settled for the Brothers Gibb instead), and with a score produced by George Martin, the incredibly odd lineup includes George Burns (improbably talk singing “Fixing a Hole”), Billy Preston (“Get Back”), Aerosmith (“Come Together”), Earth Wind and Fire (a highlight with “Got to Get You Into My Life”), Steve Martin (inevitably funny with “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”), British comedian Frankie Howerd (the sleep-inducing villain of the piece, doing “Mean Mr. Mustard”), Tommy veteran Paul Nicholas, Sandy Farina (as Strawberry Fields), Dianne Steinberg (as Lucy, doing “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”), forgotten nowhere band Stargard, Alice Cooper (“Because”), and Donald Pleasence (with an insufferable “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)).” By the time a band of robots appear with an autotuned “She’s Leaving Home,” you’ll wanna be leaving the movie.

Infamously awful, this misbegotten interpretation of the Beatles world has Peter Frampton and The Bee Gees playing the titular band and thereby insuring their future near-disappearance from the cinematic landscape.

There’s inventive costuming and art direction here (including a gazebo topped by a giant cheeseburger), but by and large, this is a disaster that’ll have you grabbing for some booze to make it all go down without a hitch (it’ll help to have some pals there to assist in an MST3K-style reading of this drek). The best (?) is saved for the end, when a massive number of stars gets together to sing the title song–see if you can spot George Benson, Elvin Bishop, Stephen Bishop, Jack Bruce, Keith Carradine, Carol Channing, Rick Derringer, Donovan, Yvonne Elliman, José Feliciano, Leif Garrett, Heart, Barry Humphries (as Dame Edna), Etta James, Dr. John, Bruce Johnston, Mark Lindsay, Nils Lofgren, Jackie Lomax, John Mayall, Curtis Mayfield, another supposed Fifth Beatle ‘Cousin Brucie’ Morrow, Peter Noone, Alan O’Day, Robert Palmer, Anita Pointer, Bonnie Raitt, Helen Reddy, Minnie Riperton, Chita Rivera, Johnny Rivers, Sha-Na-Na, Del Shannon, Joe Simon, Seals and Crofts, Connie Stevens, Al Stewart, John Stewart, Tina Turner, Frankie Valli, Gwen Verdon, Grover Washington Jr., Hank Williams Jr., Johnny Winter, Wolfman Jack, Bobby Womack, and Gary Wright! What, Liberace wasn’t available?

Birth of the Beatles

(Richard Marquand, 1979)  This TV movie (directed by Marquand, who would go on to helm Return of the Jedi) is a stiff, badly-written retelling of the boys’ meeting in Liverpool and their days as a bar band at the Keiserkellar in Hamburg. I can recall seeing it as a young Beatles fan and being immensely disappointed with it. The songs are performed by a Beatles stand-in band, Rain, and I can hardly remember much about it, except that it put me to sleep. Still, it’s available for all to see now, through the magic of You Tube. For completists only.

This TV movie (directed by Marquand, who would go on to helm Return of the Jedi) is a stiff, badly-written retelling of the boys’ meeting in Liverpool and their days as a bar band at the Keiserkellar in Hamburg. I can recall seeing it as a young Beatles fan and being immensely disappointed with it. The songs are performed by a Beatles stand-in band, Rain, and I can hardly remember much about it, except that it put me to sleep. Still, it’s available for all to see now, through the magic of You Tube. For completists only.

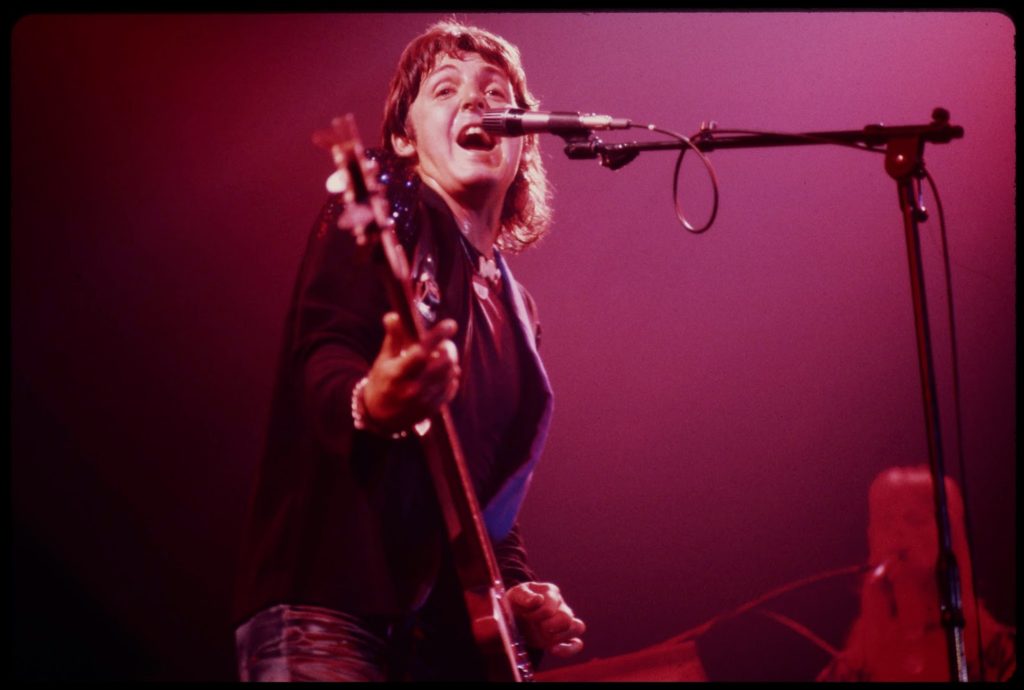

Rockshow

(Paul McCartney, 1980)

A chronicle of Paul McCartney’s tour of America alongside his band Wings (including Linda McCartney, Denny Laine and Jimmy McColloch), this straightforward concert film, filmed in Seattle, has recently been given a retouch on Blu-Ray, and it looks great (though some say the sound quality has been reduced by the compression process). Not one of the most vivid concert films, I remember it lacking a certain energy in its direction, though there’s still obvious value in seeing McCartney in his prime and before Wings began its downward slide. Songs include: “I’ve Just Seen a Face,” “The Long and Winding Road,” “Lady Madonna,” “Yesterday,” “Blackbird,” “Jet,” “Live and Let Die,” “Silly Love Songs,” “Let ‘Em In,” “My Love,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Band on the Run,” “Venus and Mars/Rock Show,” “Listen to What the Man Said,” and Denny Laine doing one of his old Moody Blues numbers “Go Now.”

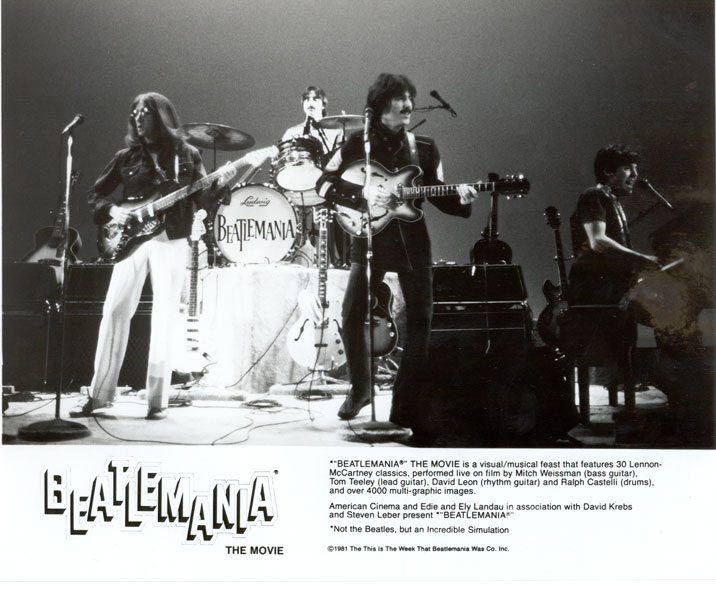

Beatlemania

(Joseph Manduke, 1981)  Best avoided unless you want to pull out what’s remaining of your hair, the cast of the Broadway hit recreate the show for film, with all the familiar tropes you might expect (including, for instance, a solarized freak-out accompanying “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and lots of boring ’60s stock footage throughout). With Mitch Weissman as Paul McCartney, Tom Teeley as George Harrison, David Leon as John Lennon, and Ralph Castelli as Ringo Starr, the performers are accurate and well-coiffed, but the film itself feels like having a weak acid eat away at your skin; it’s radically dull, despite the music being well-performed. Arguably worse than even Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and that’s a valley of achievement if there ever was one.

Best avoided unless you want to pull out what’s remaining of your hair, the cast of the Broadway hit recreate the show for film, with all the familiar tropes you might expect (including, for instance, a solarized freak-out accompanying “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and lots of boring ’60s stock footage throughout). With Mitch Weissman as Paul McCartney, Tom Teeley as George Harrison, David Leon as John Lennon, and Ralph Castelli as Ringo Starr, the performers are accurate and well-coiffed, but the film itself feels like having a weak acid eat away at your skin; it’s radically dull, despite the music being well-performed. Arguably worse than even Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and that’s a valley of achievement if there ever was one.

Caveman

(Carl Gottlieb, 1981)  It’s safe to say that only Ringo Starr emerged from the group as a credible actor, both while with The Beatles and in their latter days. The only problem is, he had terrible taste in movies. With the possible exception of the cult hits That’ll Be The Day (1973’s pretty fine kitchen-sink British drama set in the world of early 60’s rockers) and The Magic Christian, his 1969 teaming with Peter Sellers and the subversive Terry Southern, his output had been pretty poor for a long time. Anybody out there ever tried to get through Candy, Blindman, Son of Dracula, Sextette or Lisztomania? I didn’t think so. So it’s nice that he capped his big-screen career with Caveman. It ain’t no comedy masterpiece, but it’s reasonably fun, with Ringo as a hapless Homo Sapiens battling an alpha caveman (John Mathusak) while teaming with a friendly Dennis Quaid to vanquish dinosaurs, discover marijuana, and win the heart of a luscious Barbara Bach (to whom Starr is still married). With Shelley Long and Jack Gilford co-starring, it’s almost always captivating, largely due to Starr’s likability in the lead, and the lively dinosaur effects by stop-motion master Dave Allen. After this, the ageless Starr was pretty much relegated to TV commercials and Thomas The Tank Engine. But he’ll always have Caveman.

It’s safe to say that only Ringo Starr emerged from the group as a credible actor, both while with The Beatles and in their latter days. The only problem is, he had terrible taste in movies. With the possible exception of the cult hits That’ll Be The Day (1973’s pretty fine kitchen-sink British drama set in the world of early 60’s rockers) and The Magic Christian, his 1969 teaming with Peter Sellers and the subversive Terry Southern, his output had been pretty poor for a long time. Anybody out there ever tried to get through Candy, Blindman, Son of Dracula, Sextette or Lisztomania? I didn’t think so. So it’s nice that he capped his big-screen career with Caveman. It ain’t no comedy masterpiece, but it’s reasonably fun, with Ringo as a hapless Homo Sapiens battling an alpha caveman (John Mathusak) while teaming with a friendly Dennis Quaid to vanquish dinosaurs, discover marijuana, and win the heart of a luscious Barbara Bach (to whom Starr is still married). With Shelley Long and Jack Gilford co-starring, it’s almost always captivating, largely due to Starr’s likability in the lead, and the lively dinosaur effects by stop-motion master Dave Allen. After this, the ageless Starr was pretty much relegated to TV commercials and Thomas The Tank Engine. But he’ll always have Caveman.

Time Bandits

(Terry Gilliam, 1981) Now why is THIS a Beatles movie? Well, it’s the prime example of a picture from George Harrison’s production company Handmade Films, which put out an impressive lineup of films all throughout the ’80s (the company is still around, having produced Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels in the ’90s and 127 Hours in 2010, but the ’80s were its peak years). Starting with Monty Python’s Life of Brian in 1979, Harrison and the company’s co-founder, longtime Beatles associate Denis O’Dell, shepherded such acclaimed films as The Long Good Friday, The Missionary, A Private Function, Mona Lisa, Withnail and I, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, and How to Get Ahead in Advertising. Still, amongst these titles, I suspect that Terry Gilliam’s dark, time-jumping fairy tale remains the most loved of them all. Though there’s no Harrison cameo as in Life of Brian, there is a Harrison song, “Dream Away,” over the closing credits, so that helps cement my claim to this being a Beatles-related film. At any rate, Harrison deserves some credit for pursuing many daring scripts and getting the cash to make them; he turned out to be the one Beatle who really had some filmmaking savvy.

Now why is THIS a Beatles movie? Well, it’s the prime example of a picture from George Harrison’s production company Handmade Films, which put out an impressive lineup of films all throughout the ’80s (the company is still around, having produced Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels in the ’90s and 127 Hours in 2010, but the ’80s were its peak years). Starting with Monty Python’s Life of Brian in 1979, Harrison and the company’s co-founder, longtime Beatles associate Denis O’Dell, shepherded such acclaimed films as The Long Good Friday, The Missionary, A Private Function, Mona Lisa, Withnail and I, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, and How to Get Ahead in Advertising. Still, amongst these titles, I suspect that Terry Gilliam’s dark, time-jumping fairy tale remains the most loved of them all. Though there’s no Harrison cameo as in Life of Brian, there is a Harrison song, “Dream Away,” over the closing credits, so that helps cement my claim to this being a Beatles-related film. At any rate, Harrison deserves some credit for pursuing many daring scripts and getting the cash to make them; he turned out to be the one Beatle who really had some filmmaking savvy.

The Compleat Beatles

(Patrick Montgomery, 1982)

A pretty standard documentary about the band’s history, it was for a while the only film of its type, and so it has historical value there. But its standing has been eclipsed by another documentary series of greater scope, as we will see…

A pretty standard documentary about the band’s history, it was for a while the only film of its type, and so it has historical value there. But its standing has been eclipsed by another documentary series of greater scope, as we will see…

Give My Regards to Broad Street

(Peter Webb, 1984)  An awful, largely incomprehensible comedy that proves that Magical Mystery Tour was no fluke in Paul McCartney’s narrative filmmaking career; this is more of the same, only given a smoky pastel ’80s ambiance. A complete non-event, even the music fails to stick (its big hit was the suitable “No More Lonely Nights”). Ringo, ever loyal and vigilant, shows up for support and brings Barbara Bach along, and of course, Linda McCartney is there as a friendly black hole of charisma (rest her soul). Tracey Ullman, Ralph Richardson and Bryan Brown are in the mix as well, but I can’t recall even laughing once during this lazy, day-in-the-life boondoggle. Actually, I DO remember liking the animated short, Geoff Dunbar’s Rupert and the Frog Song, that preceded it; co-written and produced by Linda and Paul, with Paul providing many of the voices and the music, it was a quaint appetizer for a rancid main course.

An awful, largely incomprehensible comedy that proves that Magical Mystery Tour was no fluke in Paul McCartney’s narrative filmmaking career; this is more of the same, only given a smoky pastel ’80s ambiance. A complete non-event, even the music fails to stick (its big hit was the suitable “No More Lonely Nights”). Ringo, ever loyal and vigilant, shows up for support and brings Barbara Bach along, and of course, Linda McCartney is there as a friendly black hole of charisma (rest her soul). Tracey Ullman, Ralph Richardson and Bryan Brown are in the mix as well, but I can’t recall even laughing once during this lazy, day-in-the-life boondoggle. Actually, I DO remember liking the animated short, Geoff Dunbar’s Rupert and the Frog Song, that preceded it; co-written and produced by Linda and Paul, with Paul providing many of the voices and the music, it was a quaint appetizer for a rancid main course.

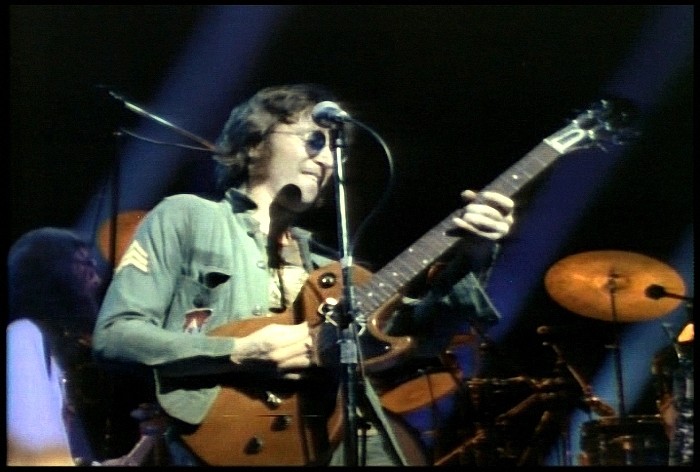

John Lennon Live in New York City

(Carol Dysinger and Carol Gephardt, 1986)  A long-unreleased 55-minute concert film shot in 1972, John Lennon Live in New York City is one of the few opportunities we now have to see the late Mr. Lennon in performance with Yoko Ono and their adopted house band Elephant Memory. Consisting largely of songs from his album Somewhere in New York City, this benefit concert is haphazardly filmed, but it’s all we have of his final full concert. The only Beatles tune delivered is “Come Together,” but his performance of, among others, “Power to the People,” “Woman is the Nigger of the World,” “New York City,” the great “Mother,” “Well Well Well,” “Instant Karma,” “Imagine,” “Cold Turkey,” and “Give Peace a Chance” are all as powerful as one might expect.

A long-unreleased 55-minute concert film shot in 1972, John Lennon Live in New York City is one of the few opportunities we now have to see the late Mr. Lennon in performance with Yoko Ono and their adopted house band Elephant Memory. Consisting largely of songs from his album Somewhere in New York City, this benefit concert is haphazardly filmed, but it’s all we have of his final full concert. The only Beatles tune delivered is “Come Together,” but his performance of, among others, “Power to the People,” “Woman is the Nigger of the World,” “New York City,” the great “Mother,” “Well Well Well,” “Instant Karma,” “Imagine,” “Cold Turkey,” and “Give Peace a Chance” are all as powerful as one might expect.

Imagine: John Lennon

(Andrew Solt, 1988)

Lennon cohort Andrew Solt was given full access to the film output of Ono and Lennon for this moving documentary surveying their lives and careers. Here we get glimpses of Lennon’s experimental films made with Yoko, their white-drenched videos for “Imagine” and Two Virgins, their spirited debates with right-winged artist with Al Capp during their famed Bed-In, and so much more. It’s not a completely successful piece–there is a whiff of sanctimony to it, but that’s to be expected, seeing as how it came only a few years after Lennon’s sad, untimely death. But, for fans of Lennon, and indeed of The Beatles, it’s got to be seen.

The Hours and Times

(Christopher Munch, 1991)

One of the most unusual Beatles-related films is Munch’s black-and-white musing on what happened during that 1963 weekend where John Lennon and Beatles manager Brian Epstein stole away together to Barcelona, leaving The Beatles behind for just a brief while. As Epstein had a mad crush on John (supposedly one of the reasons he fell for The Beatles in the first place), the film grabs hold of the possibility that Lennon gave into Epstein’s amorous feelings just once, and never again (it’s long been posited that “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away” is an ode to his closeted manager and friend). It’s an entrancing film, led by Ian Hart’s accurately abrasive portrayal of Lennon, and David Angus’ depressed Brian Epstein. A very economical 60 minutes in length, The Hours and Times is somewhat hard to find, but worth searching out. I wish more films like this were being made about the Beatle’s most snugly intimate moments.

One of the most unusual Beatles-related films is Munch’s black-and-white musing on what happened during that 1963 weekend where John Lennon and Beatles manager Brian Epstein stole away together to Barcelona, leaving The Beatles behind for just a brief while. As Epstein had a mad crush on John (supposedly one of the reasons he fell for The Beatles in the first place), the film grabs hold of the possibility that Lennon gave into Epstein’s amorous feelings just once, and never again (it’s long been posited that “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away” is an ode to his closeted manager and friend). It’s an entrancing film, led by Ian Hart’s accurately abrasive portrayal of Lennon, and David Angus’ depressed Brian Epstein. A very economical 60 minutes in length, The Hours and Times is somewhat hard to find, but worth searching out. I wish more films like this were being made about the Beatle’s most snugly intimate moments.

Backbeat

(Iain Softley, 1994)  A big step up from Birth of the Beatles, this early ’90s film more artfully covers the same territory–the small-time Hamburg days of the band’s history. The screenplay is lackluster and cliche-ridden, but at least we have Ian Hart once again playing Lennon with more energy than he did in The Hours and Times. Stephen Dorff is slightly miscast as Stu Sutcliffe, the band’s doomed one-time guitarist and Lennon’s best mate, and Sheryl Lee pops as Astrid Kercherr, the woman who crafted their hair into moptops while chronicling their early days with her photography. It’s not a particularly memorable film, honestly, but it’s still a curiosity not entirely dismissible. The soundtrack–which features Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore on guitar, REM’s Mike Mills on bass, and Nirvana’s Dave Grohl on drums (all bravely endeavoring to preserve the punky feel of the Hamberg-era Beatles)–includes “Good Golly Miss Molly,” “Long Tall Sally,” “My Bonnie,” “Money,” “Please Mr. Postman,” “Slow Down,” “Twist and Shout,” “Carol,” “Road Runner” and “Love Me Tender” (with Henry Rollins on vocals).

A big step up from Birth of the Beatles, this early ’90s film more artfully covers the same territory–the small-time Hamburg days of the band’s history. The screenplay is lackluster and cliche-ridden, but at least we have Ian Hart once again playing Lennon with more energy than he did in The Hours and Times. Stephen Dorff is slightly miscast as Stu Sutcliffe, the band’s doomed one-time guitarist and Lennon’s best mate, and Sheryl Lee pops as Astrid Kercherr, the woman who crafted their hair into moptops while chronicling their early days with her photography. It’s not a particularly memorable film, honestly, but it’s still a curiosity not entirely dismissible. The soundtrack–which features Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore on guitar, REM’s Mike Mills on bass, and Nirvana’s Dave Grohl on drums (all bravely endeavoring to preserve the punky feel of the Hamberg-era Beatles)–includes “Good Golly Miss Molly,” “Long Tall Sally,” “My Bonnie,” “Money,” “Please Mr. Postman,” “Slow Down,” “Twist and Shout,” “Carol,” “Road Runner” and “Love Me Tender” (with Henry Rollins on vocals).

The Beatles Anthology

(Kevin Godley, Bob Smeaton, and Geoff Wonfor, 1995)

A 10-hour documentary on the band’s history, it talks to every major player still living at the time and is utterly exhaustive in its research and execution. It’s basically rendered almost all subsequent documentaries covering these years rather moot, considering McCartney, Starr, Harrison and the Lennon estate gave their full cooperation to its makers. Released in conjunction with the massive 3-volume, multi-disc set that featured a reunion of sorts with the Beatles contributing new singles “Real Love” and “Free As a Bird” using demos John Lennon had recorded in the ’80s–and sending The Beatles to #1 on the singles chart for the last time–The Beatles Anthology is nearly the last word on The Beatles as a collective, as far as cinema is concerned.

The U.S vs. John Lennon

(David Leaf and John Scheinfeld, 2006)

A competent but not exactly memorable piece of documentary reportage, The U.S vs. John Lennon covers those years in the early ’70s where Lennon, recently relocated to New York City while applying for American citizenship, ends up on Richard Nixon’s infamous Enemies’ List and was then targeted by the government for deportation. The story is, of course, compelling, but this is an example of a documentary whose makers already knew all about the tale they were telling, and so a certain level of fresh discovery is abandoned in favor of by-rote full knowledge. That can be the kiss of death for any documentary film, no matter how irresistible the story may be. Still, it’s not a film without value, and certainly it works as well if not better than your average TV doc covering the same ground.

Across The Universe

(Julie Taymor, 2007)  Surely the most successful of those offbeat re-imaginings of The Beatles music, Julie Taymor (Titus, Frida) brings her dazzling feel for inventive camerawork, stunning set and costume design, and notable makeup effects to this amusement-park tour of the ’60s, following the romance between a well-to-do American student (Evan Rachel Wood) and a British artist (Jim Sturgess). From a narrative stand-point, the film doesn’t work, often becoming too precious. But the visuals, including numerous animated sequences and a star-less soundtrack of Beatles tunes (performed in sometimes clever, sometimes not-so-much fashion) is enough to keep one riding with Across the Universe without much complaint.

Surely the most successful of those offbeat re-imaginings of The Beatles music, Julie Taymor (Titus, Frida) brings her dazzling feel for inventive camerawork, stunning set and costume design, and notable makeup effects to this amusement-park tour of the ’60s, following the romance between a well-to-do American student (Evan Rachel Wood) and a British artist (Jim Sturgess). From a narrative stand-point, the film doesn’t work, often becoming too precious. But the visuals, including numerous animated sequences and a star-less soundtrack of Beatles tunes (performed in sometimes clever, sometimes not-so-much fashion) is enough to keep one riding with Across the Universe without much complaint.

Nowhere Boy

(Sam Taylor-Wood, 2009)  A sorely disappointing look at John Lennon’s twin relationships with his guardian, the stern Aunt Mimi (an excellent but underused Kristin Scott Thomas) and his estranged, party-girl mother Julia (the lively Anne-Marie Duff, the single best reason to watch the film). The script isn’t very sharp, revving up when the domestic drama gets heated, and then falling back when it focuses on Lennon himself (played by the unremarkable Aaron Taylor-Johnson). It fares worse when it concentrates on the other Beatles, drowsily rendered. It just doesn’t seem like filmmakers can get this part of the Beatles’ history right; in fact, it just might be too massive a task to expect any filmmaker to deliver a satisfying narrative portrayal of the Beatles. They’re personalities who, to date, are just too well known and loved for us to ever accept anyone else in their shoes.

A sorely disappointing look at John Lennon’s twin relationships with his guardian, the stern Aunt Mimi (an excellent but underused Kristin Scott Thomas) and his estranged, party-girl mother Julia (the lively Anne-Marie Duff, the single best reason to watch the film). The script isn’t very sharp, revving up when the domestic drama gets heated, and then falling back when it focuses on Lennon himself (played by the unremarkable Aaron Taylor-Johnson). It fares worse when it concentrates on the other Beatles, drowsily rendered. It just doesn’t seem like filmmakers can get this part of the Beatles’ history right; in fact, it just might be too massive a task to expect any filmmaker to deliver a satisfying narrative portrayal of the Beatles. They’re personalities who, to date, are just too well known and loved for us to ever accept anyone else in their shoes.

George Harrison: Living in the Material World

(Martin Scorsese, 2011)

Scorsese brings his ear for music, interest in spirituality, and mastery of documentary filmmaking to this, perhaps the best Beatles-related doc to date. With complete access to never-before seen film and photo work shot by Harrison, Living in the Material World is a sonically bright, always eloquent, and often extremely moving look at the one Beatle whose cloistered life we probably know least about. Delving into his film production work as well as his intense quest for the highest planes of existence and gratitude, Scorsese consistently surprises the viewer with his ability to get the best stories out of his subjects, including Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr (whose final moments will bring you to tears), Eric Clapton, Pattie Boyd, Klaus Voormann, Astrid Kirtcherr, George Martin, Neil Aspinall, Yoko Ono, and the entire Harrison clan (including wife Olivia and son Dhani, who can’t possibly look more like his dad). Immensely rewarding, with a three-hour length that speeds by faster than expected, Scorsese’s film is an utter marvel.

Good Ol’ Freda

(Ryan White, 2013)

A totally enjoyable look at the periphery, and yet somehow the very center of The Beatles, with the focus being the former head of their fan club, Freda Kelly, who was later selected by Brian Epstein to be the group’s secretary. It’s particularly fascinating to see a woman–and a die hard fan who saw them countless times at The Cavern Club–so blithe about her connection to the most famous men in the world, and so respectfully tight-lipped about her experiences with them (she’s asked if she ever had a love affair with a Beatle, and she kindly refuses to answer). She’s even kept her Beatles connection away from friends and family (part of her willingness to do the film was to put her experiences down on record for them). Throughout, Kelly has some ripping tales to impart, and a gentle good spirit about it all. As a film, Good Ol’ Freda is just this side of a trifle. But as trifles go, it’s a tasty one.