A Latter Day Look At Scorsese’s Last Temptation

DIRECTED BY MARTIN SCORSESE/1988

“If you look inside me you see fear, that’s all. Fear is my mother, my father, my God.”

–The Last Temptation of Christ (movie)

“What is ‘truth’? What is ‘falsehood’? Whatever gives wings to men, whatever produces great works and great souls and lifts man’s height above the earth—that is true. Whatever clips man’s wings—that is false.”

–Nikos Kazantzakis, The Last Temptation of Christ (book)

“It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God.

–Matthew 4.4

Another trip down memory lane…

Another trip down memory lane…

When I was about 10 the small town Presbyterian church my family had attended for 3 generations got a new minister, our first female minister in the church’s 100 year history. This was a church where families still held more or less “reserved” pews, the hymnals held no hymn that was less than 50 years old, and most of the deacons and elders of the church had held their positions for 20 years or more. In other words, this was a church that was not one to break with tradition, but for some reason in the late ’80s decided this was exactly what they should do.

Rev. Julie was an interesting choice for this church because, though young, she came from a missionary evangelical background—she had spent several years in a leper colony in the southern part of South Korea where she met her husband, Young-man, a son of the colony’s stewards—and held views, both socially and theologically, that could best be described as “non-traditional.” Progressive, even.

She quickly became known for her “causes.” Early on, she and a few like-minded cohorts decided to protest the ‘beer tent’ at our town’s annual Fireman’s Festival by dressing up as sad clowns and handing out disapproving cartoon pamphlets at the entrance. The following December, she took over the Christmas Play with one she had devised herself—complete with dancing angels, close-harmony singing shepherds, and a grand processional trio of kings leading ‘canopied’ camels (held up by three kids under the canvases—with the tallest kid in the middle being the ‘hump’). Another time, during an Easter service, she performed some sort of Rite of Spring in lieu of a traditional sermon, dancing in the aisles to (recorded) classical music and hurling about crepe paper banners to parishioners with legends like “Rejoice!” and “Believe!”

To a preteen, I must admit, this was all quite amusing–if a little, um, weird.

So when it came time a few years later to start taking Confirmation classes—every Wednesday, I recall—I was both eager and wary to see what Rev. Julie would possibly come up with. I was not disappointed: spaghetti dinners, meditation sessions, ping pong tournaments,… even Friday night slumber parties in that great old barn of a church in which there were, quite literally, bats in the belfry!

But my favorite was, of course, Movie Night. Once a month during the 2-year Confirmation period I think we saw, among many others, Brother Sun, Sister Moon, Romero, The Elephant Man… and, the reason I’m telling you all of this, the one we most emphatically DID NOT see, The Last Temptation of Christ.

But I do recall that Rev. Julie did in fact make the recommendation to us, calling it “the most profoundly spiritual movie ever made,” and even left a VHS copy on the church’s spindle of ‘check-out’ materials should we want to take it home and watch it with our parents. Alas, I never did, but I did catch up with the movie several years later and, after having a little more perspective on the controversy surrounding the film, I was not disappointed.

To this day, it strikes me, privately, as very much a “Rev. Julie movie”: it stirred up a lot of trouble and seemed quite unashamed about doing so!

…

Martin Scorsese’s 1988 film adaptation of the 1953 Nikos Kazantzakis novel, The Last Temptation of Christ, is quite possibly the most controversial movie made within the past 30 years. Condemned upon release by the Catholic church, decried by several Christian fundamentalist groups, its premiere was greeted with picketing, rioting, and a lot of angry press, culminating in the tragic firebombing of a movie theater in Paris, France that was showing the film. Years following the release of the film, major distributors refused to carry it, several theaters refused to show it, and one major home video rental chain, the now-defunct Blockbuster Video, refused to put it on their shelves.

So what was all the furor about, anyway? In preparing for this particular write-up, not only did I re-view the film (twice), but I also read, for the first time, the novel on which it was based. Screenwriter Paul Schrader (who had previously written Taxi Driver and Raging Bull for director Scorsese) liberally adapted the 500 page Kazantzakis novel, condensing and re-structuring the narrative where it seemed appropriate, but retained the core elements of the author’s reinterpretation of the Gospels which had then-similarly infuriated church leaders, resulting in the author’s excommunication from the Catholic church, and which delayed its translation/publication into English until after the author’s death.

Specifically, the controversies surrounding the book, and subsequently the film, are narrative and thematic elements relating to “the incessant, merciless battle between the spirit and the flesh” in the physical reality of Christ when he walked on Earth. Kazantzakis’ Christ is one who is unsure of himself, motivated by “pity and fear,” an all-too human, but yet transcendentally divine, presence—conflicted, reluctant; though immensely powerful—who is nonetheless intimately acquainted with what he has come to free mankind from: namely, sin.

In the early scenes, he, the “carpenter’s son,” is shown building crosses for the Romans and assisting them in a crucifixion of a fellow Israelite; later, he embarks on his ministry not entirely certain whether the “voices” and “torments” he receives, “like a great bird of prey clawing into [his] skull” are from the God or the Devil; still later, he begs his strongest (and most faithful) disciple, the Zealot and warrior Judas Iscariot, to betray him to the Romans in order to fulfill his ministry.

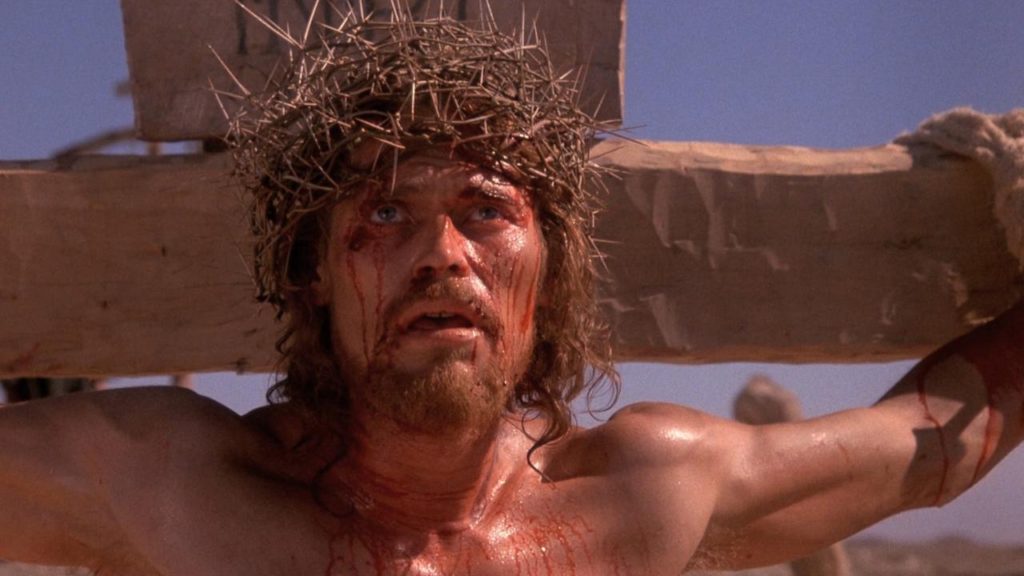

These are departures from the Gospels, which one imagines did not endear itself to its critics, but it is undoubtedly the narrative’s penultimate sequence that represents a complete, heretical break from the teachings of most major Christian sources of authority: Jesus, in a dream or vision of sorts, receives a visit from his “Guardian Angel,” steps off the cross, puts aside his ministry, and lives as a man—marries, has children, works, grows old—before realizing the “Angel” is in fact Satan in disguise, and thus his Last Temptation, and so breaks the vision and returns to die on the cross; his life and purpose now “accomplished,” representing a spiritual victory over the temptations of the flesh.

…

Christ and Magdalene, in Jesus’ Last Temptation dream-vision

Now, it is one thing to read about this, and still another to be shown it.

And that’s where we (finally!) get to the film itself. In preparing for this write-up I also re-read the Gospels and, while reading them, tried to focus very hard on Christ as a living, breathing person wandering about Galilee and its environs. What would he be like?

The consistent point between all four accounts of his life, ministry, death, and resurrection is Christ’s tendency to illustrate his teachings with characters that may or may not have lived, and incidents which may or may not have happened, but which are nonetheless all true. The sower casting seeds in the field. The prodigal son who returns to his father’s house and favor. The faithful steward who wisely (and correctly) sets a table for his master’s coming.

Parables, of course. The Jesus of the Gospels is a master storyteller and, like all storytellers, places thoughts and ideas in an imaginative context, thus spurring subsequent discussion, interpretation, and debate. (Which, obviously, is still going on today.) In cinematic terms, to be shown a challenging sequence of images adds yet another degree of immediacy.

And it is one that this particular director, Martin Scorsese, was well prepared for. In his earlier Mean Streets (1973), Scorsese depicts a low-level Mafia enforcer imagining the fires of Hell while holding his hand over an open flame; in Taxi Driver (1976), a God’s-eye-view (i.e., a tracking overhead shot) on a scene of blood and carnage evokes the suffering and pain which precedes salvation; in Raging Bull (1980), a boxer shadowboxing in a ring becomes an improbably touching metaphor for a weak, troubled man trying, and failing, to effectively fight his own demons. (In Scorsese’s first studio film, Boxcar Bertha (1972), there is even a dream sequence that includes a crucifixion!)

From the blood splashing across Jesus’ face in an early scene as he holds the Zealot’s feet in place, and a Roman centurion nails them to the cross, to the penultimate scene where an aged Jesus drags himself on reopened wounds from his deathbed back across the field to Golgotha, Scorsese’s intimate, sensually detailed style of filmmaking makes for a very different sort of religious epic. So I tend to think of Scorsese, at least in this phase of his career, as a deeply spiritual filmmaker who introduced religious elements to his movies—consciously or unconsciously, and perhaps resulting from his Italian-Catholic upbringing—in a unique and challenging manner.

And all the more value for it. Willem Dafoe, I suppose, is no one’s idea of Jesus, Barbara Hershey is an earthy and sexual Mary Magdalene, experimental theater director Andre Gregory is a raging inferno, a true “voice in the wilderness,” as John the Baptist, pop star David Bowie makes a rather unlikely Pontius Pilate—and the less said about a heavily Brooklyn-accented Harvey Keitel as Judas Iscariot, the better—but it’s all completely unexpected. As is a lush electronic score by former Genesis frontman Peter Gabriel, vivid and heavily-saturated photography from Michael Ballhaus, and sharp, jagged scene-cutting from editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

…

From The Manger To The Cross (1912)

This Slightly Obsessed Moviewatcher has seen many a religious epic depicting the life of Christ—from 1912’s From the Manger to the Cross, through Cecil B. DeMille’s 1927 King of Kings, to the super-productions of the ’60s like the 1961 King of Kings and 1965’s The Greatest Story Ever Told—and, while most have their merits, relatively speaking, very few (or none) manage to convince one that Jesus was a flesh-and-blood person who walked around, told stories, ate and drank with ‘low company,’ or was anything approaching a human being with desires or feelings. Watching H.B. Warner, Max von Sydow, Robert Powell et al., one imagines them floating across the screen, almost as if their feet aren’t touching the ground. (Off-topic, but I’d suggest a 1969 movie, The Milky Way, by that playful surrealist, Luis Buñuel—he of the famous “Thank God I’m an atheist” comment—that contains possibly the very first screen depiction of a more realistic and ‘earthy’ on-screen Christ.)

Perhaps I’ve emphasized the more dramatic instances of Christ’s more human qualities in Scorsese and Kazantzakis’ Christ in this write-up, but I would nonetheless like to make clear that, if I haven’t already, that the Christ of The Last Temptation, precisely because he is so unexpectedly and realistically human, is all the more powerful for his ultimate transcendence of his frail humanity into something quite Other.

…

Once again, in a movie that tends to shock and upset one’s expectations, the impact of such a work of art—whether as a book or film—depends on its readers or viewers being open to the experience of their faith, beliefs, whathaveyou being challenged. The Last Temptation of Christ aims to depict the Gospels in a new and different way, one that may not always be comfortable for its readers or viewers, but which should nonetheless provoke thought, discussion, and debate that will be useful, and ultimately illuminating.

Personally, I will always associate this movie with my confirmation pastor, Rev. Julie, dancing down the church aisles at Easter: it made me super uncomfortable, but it did do something to break down some of those staid and suffocating traditions of the past!