His Career Is Like A Box Of Chocolates

“Do you think he knows that this is by far his most important work, that it will go on to outshine everything else he’s ever done or will do?” That was by brother’s question to me about Tom Hanks, just after seeing Toy Story 3. In that animated instant classic, Hanks once again voiced Woody the vintage toy cowboy. And yes, I suspect Hanks has in fact come around to understanding this. This is not to say that the entirety of Hanks’ considerable career is paltry in the face of a long-running voice acting gig. Rather, it’s a testament to not only the deep, essential power of the Toy Story films, but in a way, to the very scope and resonance of the rest of filmography.

“Do you think he knows that this is by far his most important work, that it will go on to outshine everything else he’s ever done or will do?” That was by brother’s question to me about Tom Hanks, just after seeing Toy Story 3. In that animated instant classic, Hanks once again voiced Woody the vintage toy cowboy. And yes, I suspect Hanks has in fact come around to understanding this. This is not to say that the entirety of Hanks’ considerable career is paltry in the face of a long-running voice acting gig. Rather, it’s a testament to not only the deep, essential power of the Toy Story films, but in a way, to the very scope and resonance of the rest of filmography.

But before Hanks achieved other immortality as Forrest Gump or broke ground playing an AIDS sufferer in Philadelphia, he was a comedy actor. Hailing from television situation comedy (specifically the straight-dudes-in-drag series Bosom Buddies), semi-lowbrow, then mainstream comedy was how the actor spent much of the 1980s. I vividly recall when he scored his first Best Actor nomination for the 1988 smash Big. As a comedy actor, I suppose he had no chance of winning, and knew it. In the very moment of his name not being read, Hanks leaded over to give his wife a kiss. (the Oscar went to Dustin Hoffman for Rain Man).

In that moment, one that I assumed would be that “comedy actor’s” one and only shot at the Oscar, Hanks’ genuine nature shined though, as he understood that some things were more important than winning an award. It’s moments like these that have earned him a reputation as one of Hollywood’s nicest guys. However true or untrue that reputation is, we certainly have little trouble buying into it. Indeed, in Julie Salomon’s absorbing chronicle of the making and unmaking of Brian De Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, The Devil’s Candy, Hanks is one of very few to emerge from the book unscathed. In 1995, he would make his directorial debut with the beloved That Thing You Do! Other major acting work includes Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, Ron Howard’s Apollo 13, and Frank Darabont’s The Green Mile.

All these many years later, Tom Hanks continues to impress us with his resonant, relatable performances. His careful choices have become ever so much riskier (Cloud Atlas, The Ladykillers), even as his established reputation takes greater root in the cultural soil.

His “Toy Story” work may outshine all the rest of it, but the rest of it is certainly nothing to sneeze at. Tom Hanks remains one of our biggest and most well respected stars, and will be remembered. He’s done a very rare thing for a Hollywood superstar: He’s earned our trust.

Charlie Wilson’s War

(2007, Universal Pictures, dir. Mike Nichols)

by Erik Yates

Tom Hanks’ “late” period has had some solid entries, but nothing that is as known as his classic period films of the 1980’s and 90’s, with everything from Splash to Big, and of course Philadelphia, Forrest Gump, Apollo 13, Saving Private Ryan, and A League of Their Own. The later period has some good ones, such as Road to Perdition, and it also has Hanks doing his best to keep the Dan Brown novels respectable with The Da Vinci Code and Angels & Demons.

Tom Hanks’ “late” period has had some solid entries, but nothing that is as known as his classic period films of the 1980’s and 90’s, with everything from Splash to Big, and of course Philadelphia, Forrest Gump, Apollo 13, Saving Private Ryan, and A League of Their Own. The later period has some good ones, such as Road to Perdition, and it also has Hanks doing his best to keep the Dan Brown novels respectable with The Da Vinci Code and Angels & Demons.

Sandwiched in between these films, I found a smaller film that seemed to do very little at the box office despite it’s enormous amount of talent. That film is Charlie Wilson’s War. Written by Aaron Sorkin (The West Wing, The Social Network) and directed by Mike Nichols (The Graduate, The Birdcage) in his final directorial effort, the film boasts as much talent on camera as it does off. Starring Tom Hanks, the cast also includes Julia Roberts, the late-great Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, Emily Blunt, John Slattery, Om Puri, Rizwan Manji, and Ned Beatty.

The film is a strong behind-the-scenes look at how in the 1980’s, America was able to get Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan (an impossible political pairing even today) to work together to funnel weapons and supplies to the Afghanistan freedom fighters who were taking on the invading Soviet Union. The Texas democratic congressman who made this all happen was Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks) working alongside CIA agent Gus Avrakotos (Hoffman) with financing and help with political leveraging from Houston Billionaire, Joanne Herring (Roberts). Everyone is perfectly cast and the film has strong humor amidst an intriguing story. Tom Hanks has the near impossible role in playing Charlie Wilson, however, as the congressman was a known philanderer, and was investigated for doing cocaine and other scrupulous behavior. Hanks is up for the challenge, but he seems to be combatting the all-American image he has built up for several decades turning this story more into a white-washed feel-good success story instead of the juxtaposition it really is with a morally flawed man clawing his way to finally use the power he has in Congress to do the only moral thing he seems to have been a part of. On the whole a valuable, yet sadly overlooked, gem in Mr. Hanks’ catalogue.

Saving Mr. Banks

(2013, Walt Disney Pictures, dir. John Lee Hancock)

by Krystal Lyon

Ph: Franois Duhamel

Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

It takes a certain kind of actor to channel Walt Disney, to be playful and curious but at the same time ambitious and driven. So who other than the man who played the pre-teen stuck in an adult’s body, Big, and also the man who helped save Private Ryan, Tom Hanks. In Saving Mr. Banks, Hank’s role is limited, this is really Emma Thompson’s moment to shine as P.L. Travers the writer of Mary Poppins, but when he is on screen he’s pure magic. Disney is magic and so is Tom Hanks! (Who else can make you cry when a volleyball named Wilson floats away?)

It takes a certain kind of actor to channel Walt Disney, to be playful and curious but at the same time ambitious and driven. So who other than the man who played the pre-teen stuck in an adult’s body, Big, and also the man who helped save Private Ryan, Tom Hanks. In Saving Mr. Banks, Hank’s role is limited, this is really Emma Thompson’s moment to shine as P.L. Travers the writer of Mary Poppins, but when he is on screen he’s pure magic. Disney is magic and so is Tom Hanks! (Who else can make you cry when a volleyball named Wilson floats away?)

I believe that Hanks’ story telling ability is what sets him apart and made him perfect as Disney. There is a scene where Disney is telling Travers a story from his childhood. He’s opening up to her so that he can gain her trust and the rights to make Mary Poppins. All along he has tried to handle their relationship as business but he has learned her need to be known before she can trust him with this precious story. He looks at her with understanding and says, “George Banks will be saved. He will be redeemed.” He’s believed and the rest is Disney magic history.

Hanks has always been able to look into the camera and tell a story that is believable. Think of the scene in Saving Private Ryan where he finally tells his men that he is an English teacher from Pennsylvania. He shared the story of losing his wife on a radio program in Sleepless In Seattle and had women from all over the country asking him out on dates. Hanks is relatable and he has a sincere quality that makes him believable, the everyman, a modern day Jimmy Stewart. And I just want to end this by saying I’ve loved him since Splash and The Man With One Red Shoe. Tom Hanks, you are sincerely my favorite!

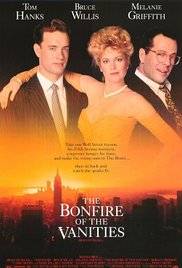

The Bonfire of the Vanities

(1990, Warner Brothers, dir. Brian De Palma)

by Robert Hornak

We’re well into what I’d call Hanks’ “late pre-prestige” period, just before he caught the Spielberg-Zemeckis-Ephron train to Oscars, autonomy, and rom-com immortality. He spent the 80s flexing so many of the same very talented muscles, in comedies and dramas, and in one case (Punchline) demonstrating how the comedy can be the drama, you can understand why he might feel a little envelope-pushy, wanting to yank his resume up a notch, or maybe just shake up an incredibly successful rut. I imagine when he read the script for this movie, a straight-up satire, he saw a chance to shock his persona with a newer, smarter jolt – a mean-spirited, morally ambiguous leap-frog over all the broad, sentimental, and/or melodramatic stuff he’d already reinvented into his lanky image. I also imagine he never guessed it could all go so wrong.

We’re well into what I’d call Hanks’ “late pre-prestige” period, just before he caught the Spielberg-Zemeckis-Ephron train to Oscars, autonomy, and rom-com immortality. He spent the 80s flexing so many of the same very talented muscles, in comedies and dramas, and in one case (Punchline) demonstrating how the comedy can be the drama, you can understand why he might feel a little envelope-pushy, wanting to yank his resume up a notch, or maybe just shake up an incredibly successful rut. I imagine when he read the script for this movie, a straight-up satire, he saw a chance to shock his persona with a newer, smarter jolt – a mean-spirited, morally ambiguous leap-frog over all the broad, sentimental, and/or melodramatic stuff he’d already reinvented into his lanky image. I also imagine he never guessed it could all go so wrong.

The movie gave me plenty of time to also be online, where I learned that a “bonfire of the vanities” is a late medieval “burning of objects condemned by authorities as occasions for sin.” Unfortunately, the movie was an occasion for my sin, if using foul words to rebuke your television is a sin. It takes a perfectly worthy satirical premise (South Bronx hit-and-run by Wall Street hawk becomes cynical leverage for various factions’ political gain), loads it with shrill performances servicing thin dialogue, and spackles it with the least insightful framing voiceover since my own first-year film school project.

But worse than all that is the regular infusion of sympathy for Hanks. Making us care too much for the target of your attack is a recipe for a failed satire. Then, it’s kinda not his fault really – the man still has too much Big on him, and he’s just too earnest for us to believe he’s the cut-throat businessman or the philandering husband. Surely by the time he’s blasting holes in his apartment with a high-power rifle, we’ve left Hanksland for good, and any buffer we might’ve had against all those other widely-lensed ideological mouthpieces is shot away.

Meanwhile, Brian De Palma (who I like) lolls as the director of a broad movie that should’ve been dead-pan, to mirror the m.o. of our allegedly omniscient narrator. If De Palma’d gone all the way with either a bravado or a classical style, it might’ve played. But the intermittent raft of unmotivated De Palma-ish split-screens, shoehorned-in split-focus diopters, an awkwardly executed dolly-zoom and a multitude of conspicuous super-low angles makes it feel like De Palma was assigned the film against his will and only sporadically challenged his own boredom.

So: De Palma’s not engaged, Hanks is adrift, and characters just keep yelling. Maybe I can cynically leverage the terrible tragedy of this movie for my two hours back.

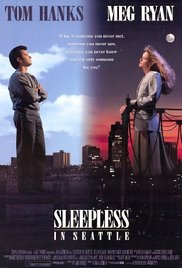

Sleepless in Seattle

(1993, TriStar Pictures, dir. Nora Ephron)

by Jim Tudor

Considering that I’m not the target audience for Sleepless in Seatle, I enjoyed enough of the film to say that enjoyed it on the whole. Director/writer Nora Ephron was no slouch when she was in the zone, and the film is marvelously shot by Ingmar Bergman’s cinematographer Sven Nykvist. These people, along with an even-more-likable-than-usual Tom Hanks, are the primary purveyors of Sleepless‘s pleasures. Yet, my reservations are intact, and are definite.

Considering that I’m not the target audience for Sleepless in Seatle, I enjoyed enough of the film to say that enjoyed it on the whole. Director/writer Nora Ephron was no slouch when she was in the zone, and the film is marvelously shot by Ingmar Bergman’s cinematographer Sven Nykvist. These people, along with an even-more-likable-than-usual Tom Hanks, are the primary purveyors of Sleepless‘s pleasures. Yet, my reservations are intact, and are definite.According to rom-com formula, at least one of the two effervescent, adorable leads must be shackled to a stooge. The eventual ditching of the stooge in question is typically a major part of the dramatic tension. In this case, that Meg Ryan is set to marry a boring, sneezy Bill Pullman. We’re meant to view him as the stooge whom she shouldn’t settle for. But here’s the thing – this being a contemporary rom-com, unwilling to go the easy route of making his character, say, a cheater or surly, he remains a completely nice, if sniffling, guy. On the flip side, Meg Ryan spends the whole movie in a heightened state of stalker-like obsession with Tom Hanks’ character she hasn’t met, a widower of a year and a half who’s young son coerces him into sharing his heartbreak on national radio under the guise “Sleepless in Seattle”. His sense of lost love and his arc of returning to dating is the quality half of the story.

Although I very much did enjoy Tom Hanks and many of the supporting players in the film (David Hyde Pierce, Rosie O’Donnell, Rob Reiner), Meg Ryan and her spastically gesticulating Shatter-esque performance was definitely a struggle. I’ve never disliked Ryan in a role as much as I disliked her here. I was rooting for Bill Pullman to dump her.

I could be wrong, but I recall this as the film that popularized the term “chick movie”. Certainly, it is one. And in it, Tom Hanks refers to its own often-discussed classic Hollywood springboard An Affair to Remember that way. Personal biology aside, considering that Affair never did much for me, I suppose it’s a pleasant surprise that Sleepless did not in fact put me to sleep.

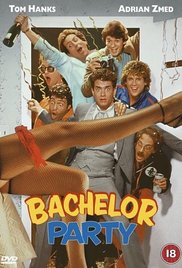

Bachelor Party

(1984, Bachelor Party Productions, dir. Neal Israel)

by Randall Yelverton

BACHELOR PARTY, Tawny Kitaen, Tom Hanks, 1984.TM and Copyright © 20th Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved..

Bachelor Party is a dumb, raunchy comedy with not much to recommend it except for some fun party tunes by Oingo Boingo (who was the official house band for 1980s comedies) and the charm of Tom Hanks which even shines through the film’s low ambitions. (There’s also a shot of donkey snorting lines of coke which is, at least, novel.) Hanks plays a character that accommodates his friends’ wild desires at his bachelor party, but is content to stand back and watch them debauch. He’s committed to his true love Tawny Kitaen, a sweet rich girl who is marrying him even though he is a school bus driver with low ambitions. Her ultra-WASPy parents are not pleased.

Bachelor Party is a dumb, raunchy comedy with not much to recommend it except for some fun party tunes by Oingo Boingo (who was the official house band for 1980s comedies) and the charm of Tom Hanks which even shines through the film’s low ambitions. (There’s also a shot of donkey snorting lines of coke which is, at least, novel.) Hanks plays a character that accommodates his friends’ wild desires at his bachelor party, but is content to stand back and watch them debauch. He’s committed to his true love Tawny Kitaen, a sweet rich girl who is marrying him even though he is a school bus driver with low ambitions. Her ultra-WASPy parents are not pleased.

Bachelor Party, like so many of its contemporaries, is a snobs versus slobs comedy. Hanks and his crude doofus pals face off against the upper crust country club set. The film was written by Pat Proft and Neal Israel who also wrote Police Academy. The film has the freewheeling stupidity of a Police Academy film with Hanks serving in the good-spirited Steve Guttenberg anchor role. While the world goes nuts around them, they face everything with a quip and a smile. Bachelor Party is most notable for demonstrating the ability of Hanks to elevate poor material and to view in contrast to his more weighty and accomplished later roles like Philadelphia which utilized the actor’s ineffable charms to draw audiences into more urgent scenarios.

The Road to Perdition

(2002, DreamWorks SKG, dir. Sam Mendes)

by Sharon Autenrieth

Road to Perdition is several things at once: a gangster film, revenge film, coming of age story, but perhaps above all a story of fathers and sons. Michael Sullivan is 12 years old and like many young boys wants to better understand his stern, silent father. What does he really do that requires carrying a gun to work? Unfortunately for Michael, his dad is a mob hitman and the son’s discovery of the father’s work will bring disaster on their family. Before long, they have lost the rest of their family and are both on the run from the mob and in pursuit of a killer.

Road to Perdition is several things at once: a gangster film, revenge film, coming of age story, but perhaps above all a story of fathers and sons. Michael Sullivan is 12 years old and like many young boys wants to better understand his stern, silent father. What does he really do that requires carrying a gun to work? Unfortunately for Michael, his dad is a mob hitman and the son’s discovery of the father’s work will bring disaster on their family. Before long, they have lost the rest of their family and are both on the run from the mob and in pursuit of a killer.

Tom Hanks is the elder Sullivan, also named Michael. He is a serious man: watchful and restrained. Beyond his wife and children, his loyalty is to his own father figure, the local mob boss, John Rooney (Paul Newman). There is love between Rooney and the fatherless boy he raised and now employs; but there’s also another son, the Rooney heir (Daniel Craig), who is craven, greedy, and jealous of his father’s affections.

In Road to Perdition the usually open and likeable Hanks is reserved – and often violent – but there is still a basic decency about him ill-suited to his line of work. In fact, if there’s one thing about Michael Sullivan that seems implausible, it’s his naiveté. He expects far more honor among criminals than is reasonable, and seems genuinely surprised that his superiors don’t support his principled quest to kill the man who has murdered his wife and younger child. When Michael pleads with Rooney to turn over the killer, Rooney reminds him that they are all murderers. This is the life they’ve chosen, and they must live by its rules.

Sam Mendes directed Road to Perdition, as a dark, somber, elegiac movie. The supporting cast (including Jude Law as a truly repulsive hitman) is excellent. Watching it is a reminder of what a fantastic actor Paul Newman was, even in his final years. And while it may be a bit hard to buy everyman Tom Hanks as a mob enforcer – simply because he’s Tom Hanks – he delivers a strong performance, particularly in the scenes of father and son discovering each other when everything else has been stripped away.

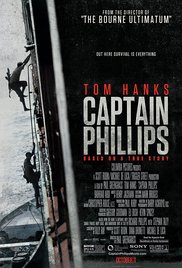

Captain Phillips

(2013, Scott Rudin Productions, dir. Paul Greengrass)

by Paul Hibbard

Captain Phillips (2013)

Tom Hanks, left, and Mahat Ali

Throughout his career, Tom Hanks has done a fine job of threading the line between Hollywood and regular guy. His performance as Captain Richard Phillips seems to be the ultimate culmination of those two skills. Nothing about Hanks in Captain Phillips is unrecognizable to us “regular” people. His slightly slumping demeanor; his anxiety-filled form of leadership; his dad body. He is an average, regular guy.

Throughout his career, Tom Hanks has done a fine job of threading the line between Hollywood and regular guy. His performance as Captain Richard Phillips seems to be the ultimate culmination of those two skills. Nothing about Hanks in Captain Phillips is unrecognizable to us “regular” people. His slightly slumping demeanor; his anxiety-filled form of leadership; his dad body. He is an average, regular guy.

Yet his Hollywood charisma and presence is still there. There’s something real and yet inspiring about Hanks’ performance. He is both someone you could have a beer with at a barbecue and someone who belongs on the big screen.

And that helps bring you into the movie Captain Phillips. He is the key to the film. Even though the film is based on true events, this is a movie that can lose the audience. It can cause them to question how something so spectacular really happened. Yet with Hanks as Phillips, he reigns in the believability without compromising the magic.

This is not at all meant to take credit away from supporting actor Barkhad Abdi or director Paul Greengrass. But Hanks is the heart. And towards the end, when Richard Phillips makes a series of choices that are either incredibly savvy or incredibly stupid (or a mixed bag of both), he personifies heroism. It’s not about doing what’s right. It’s about doing what you think is right, even if you are not positive it is right. Decisions made without questioning yourself, that may lead to a painful end for all involved.