Jake Gyllenhaal And Company Pack A Melodramatic Punch

DIRECTED BY ANTIONE FUQUA/2015

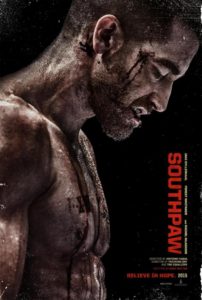

The new boxing film Southpaw is a very good boxing melodrama that thinks it’s a serious drama. Although the film hits hard with tragedy and pain, it is, at the end of the day, a kind of R-rated, deeply bruised hero’s journey, owing more to Rocky than the real world unease of Raging Bull. But more than that, Southpaw is a contemporary take on the Book of Job. Jake Gyllenhaal, impressively beefed and chiseled in another immersive role of physical transformation following his gaunt turn in last year’s Nightcrawler, is heavyweight boxing champ Billy Hope.

The new boxing film Southpaw is a very good boxing melodrama that thinks it’s a serious drama. Although the film hits hard with tragedy and pain, it is, at the end of the day, a kind of R-rated, deeply bruised hero’s journey, owing more to Rocky than the real world unease of Raging Bull. But more than that, Southpaw is a contemporary take on the Book of Job. Jake Gyllenhaal, impressively beefed and chiseled in another immersive role of physical transformation following his gaunt turn in last year’s Nightcrawler, is heavyweight boxing champ Billy Hope.

When we meet him, he is on top of the world, having gone undefeated for 30+ matches. Billy’s strategy, if it can be called that, is to hit hard. He’s very, very good at it. His meteoric success has already landed him an incredible mansion, a fleet of cool cars, and all the friends money can buy. He’s married to a sexy and smart Rachel McAdams, the right woman for him in many ways. She knows how to care for him, his career, and their daughter (Oona Laurence). Indeed, as we meet Billy Hope, it’s safe to say that he has it all. But when life hits back, it becomes quickly obvious that he has no defensive skill. Before long, Billy Hope loses everything. Directed by the visual stylist Antione Fuqua, who not even a year ago gave the world the underrated Denzel Washington lark The Equalizer, Southpaw at times haphazardly balances his Fincher-esque sense of artificial gloss and managed environment with the screenplay’s desired rough and tumble “reality”. But despite an ultimately familiar and predictable story arc in which former glory must be re-attained against all odds, Southpaw works, particularly as an unlikely summer release. It’s stakes may be resting on an exhausting truckload of drummed-up tragedy, but when considered alongside of the multiplex fluff it’s playing alongside of, its greater perceived weight will appeal to many, and not altogether unjustly.

Key to all of this is Gyllenhaal, who plays his character as an unbreakable chump who then finds himself utterly broken with nothing to fall back on.

Although Hope’s story resembles aspects of Rocky V (in which the champ loses everything) and its follow-up Rocky Balboa (the One Last Grasp For Glory), his inarticulate demeanor, unlike Stallone’s, is anything but endearing. Hope is that under-educated raging juggernaut who beat his way to fame and material success despite never learning to communicate without swearing every other word. His personality is already nil when we meet him, making the empathy we feel for the character all the more impressive, a result of Gyllenhaal’s unrelenting performance of raw, damaged humanity.

Hope spends much of the film in a depressive funk, a partially self-made victim of random violence, his own lack of self control, and a system that loves to tell him “no”. By the time he ends up cleaning toilets in a neighborhood gym, it’s all he can do to beg the altruistic once-burned-twice-shy owner Tick Wills, played by Forest Whitaker (sporting a knit hat and one foggy eye) to train him for a return bout. And yet, much of what Billy’s already lost can never be regained.

As far as this type of boxing tale goes, this critic openly prefers a film like Rocky Balboa, a film that for all its formula and inevitability (by design), understands legacy and loss better than this one does. As for director Fuqua, who is taking some off-kilter paths on his journey to respectable name recognition, he remains more at home with The Equalizer, with its stylistic aesthetic reinforcing its subtle detachment from reality.

Hailing from the awards-savvy Weinstein Company, the scuttlebutt on the film has been a mixture of glowing advance acclaim for Gyllenhaal with a dose of Cannes Film Festival drama. Despite its summer release timing, it’s hard to deny an air of hard-to-pinpoint lingering self-importance permeating the movie. Yet, Southpaw manages to come from behind and hit effectively enough to score as an engaging crowd pleaser. In Fuqua’s world in which every trash pile is color managed and harsh yellow pools of light mixed with shadow is visual shorthand for “gritty”, it’s a bit of a pleasure to watch Southpaw, like its imperfect protagonist, transcend the hand its dealt.