Duality and Mystery Dominate Ingmar Bergman’s 1960’s Masterpiece

DIRECTED BY INGMAR BERGMAN/SWEDISH/1966

STREET DATE: FEBRUARY 10, 2004/MGM

This review was written in 2004 as part of a series of Bergman reviews covering each film in a then-newly released six-disc DVD box set from MGM. In March of 2014, Criterion issued an improved dual format Blu-ray/DVD release of Persona. I share this in observation of Ingmar Bergman’s centennial in the current month of July 2018.

*****

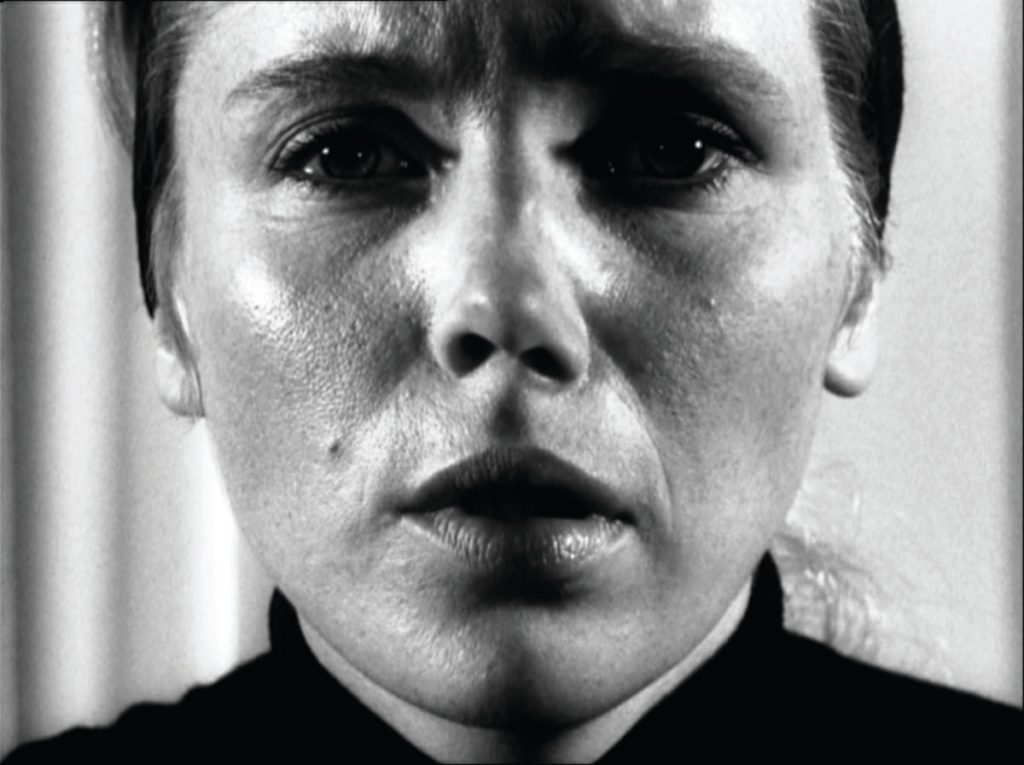

Ingmar Bergman’s Persona is cinematic dynamite. There’s so much to say about the film, I almost can’t talk about it. Which may be the point – the film centers around two women, a traumatized silent actress (Liv Ullmann) and her chatty neurotic caretaker (Bibi Andersson). One says so much the other needn’t talk at all.

Ingmar Bergman’s Persona is cinematic dynamite. There’s so much to say about the film, I almost can’t talk about it. Which may be the point – the film centers around two women, a traumatized silent actress (Liv Ullmann) and her chatty neurotic caretaker (Bibi Andersson). One says so much the other needn’t talk at all.

But the question is, just what is being said? I don’t necessarily mean said by Andersonn’s character, but rather by Bergman himself. Persona stands as one of the great deconstructionist film of the 1960s, with the director frequently pulling the rug out from under the viewer just as the plot is getting interesting to remind us that it’s only a movie. The film opens with a montage of film threading through a projector, images of cartoons and silent comedy, as well as brief glimpses of previous Bergman films.

Accompanied by an odd atonal score, this sequence ranks among the most experimental ever presented in a well-known film. Although the “A-plot” of the two women, who are similar in appearance but remote in other ways, is absolutely involving once it gets going, Bergman tends to stop the flow throughout the film by having a character break the fourth wall, revealing film equipment, or simulating a film breakage. As a testament to the amazing performances, the story of the two women is always able to resume to its full intensity.

Throughout it all Bergman is exploring our own perceptions, as well as relationships, and possibly dualities, among many other things, including his usual wrestlings with faith and life. Masterfully shot in stark black and white (by celebrated Bergman cinematographer Sven Nykvist) on the director’s remote home island of Fårö, the story itself, deconstructionist elements completely withstanding, is subject to several interpretations. What this ultimately means is that we’re dealing with a very, VERY rich piece of cinema; on the level of causing some serious long term cranium aching. While it may prove unwise to divorce the actress’ plot from Bergman’s postmodern tinkering, it can and probably should be done for the interest of brevity. (This is one DVD that could easily inspire a write-up the length of a short book. And it manages to do this in the film’s remarkably short eighty-three minute running time.)

Andersson’s nurse character Alma is assigned to assist Ullmann’s mute actress Elisabeth Vogler who has recently withdrawn into herself as a result of some sort of psychological fit. Alma’s world of stability begins to slowly breakdown as she is compelled to reveal more and more of herself to the leering and silent Elisabeth. Although Elisabeth won’t verbally reply, it is obvious that she is enraptured by every word Alma has to say. But is Elisabeth being a true confidant, or is she merely mentally noting Alma’s own psychology for later theatrical purposes?

Bergman is no doubt fascinated by the notion of the vampire as a metaphor, as Elisabeth is often seen in some very vampiric ways. Considering the director’s shifting personal life at the time this film was being made – leaving Andersson for Ullmann – there is little question that he is studying his own artistic and relational guilt, “sucking the life” from an individual and moving on as he sees fit. One needs not be familiar with this extra level of fact in the making of Persona in order to derive intellectual satisfaction from the film, but this is one case where it certainly helps to know a thing or two about the artist before partaking in his art.

MGM’s DVD of Persona, while not quite being on the level of some of Criterion’s Bergman offerings, is admirable all the same. Nykvist’s photography snaps to life in scene after gloriously shot scene. The English subtitles (translated from the film’s original Swedish dialogue) are always clear and readable, and the sound itself sounds every bit as fresh as it probably sounded upon its release in 1966. Bergman biographer and Jesuit priest Marc Gervais provides a strangely snappy but refreshingly unpretentious commentary on the film. There is also an informative featurette, “A Poem in Images”, and brief modern day interviews with the two stars. It should be noted that this is the original, unrated, uncensored theatrical version of the film, which means it contains certain thematic elements and sexually frank dialogue not suitable children and sensitive viewers.

If dissecting heady films with multiple levels of understanding is your cup of tea, and if you prefer your movies strange and non-traditional, then by all means waste no time in seeing this world cinema classic. Persona, as unique as it is, was right at home in the turbulent 1960s, and although that era is long gone, its legacy still lingers, as will the haunting images of Bergman’s introspective masterpiece once you’ve seen it.