Penultimate 2017/18 Duck Soup Cinema Presents All-Time Film Masterpiece

Overture Center’s Capitol Theater

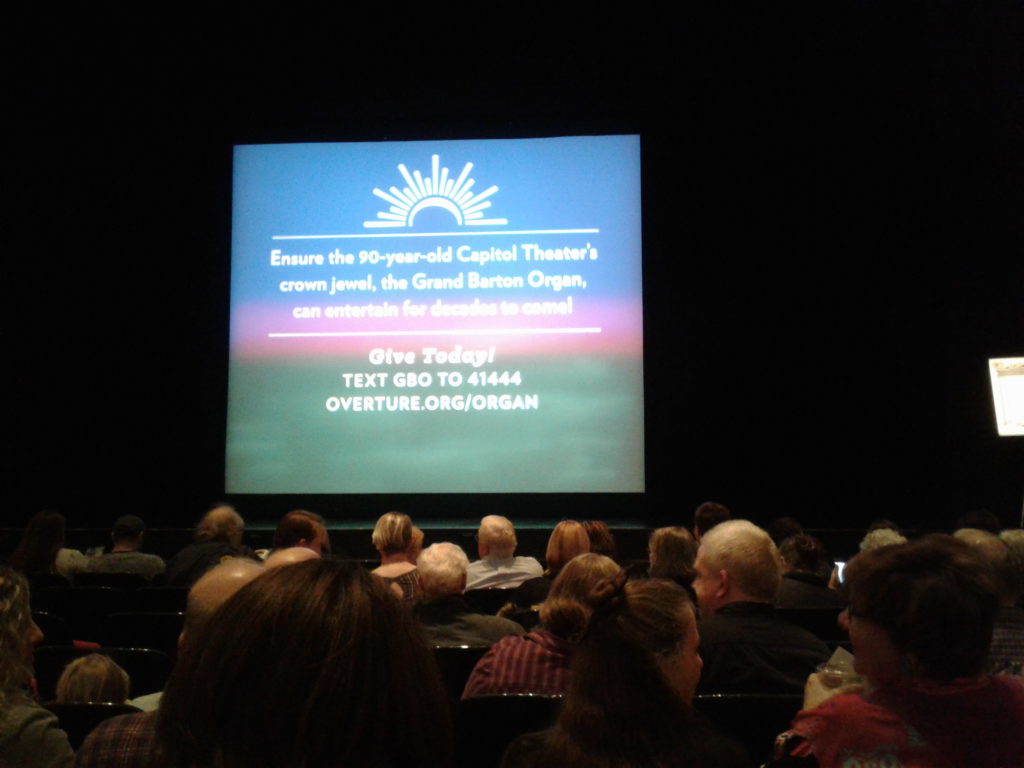

For 31 seasons, Madison, Wisconsin’s Overture Center for the Arts (formerly Madison Civic Center) has offered 2 – 5 showings per year of silent movies in its historic Capitol Theater (formerly Oscar Mayer Theater, rededicated in 2005 under its original 1928 venue name) as accompanied on the theater’s Grand Barton Organ, one of the last theater organs of its kind in the country. Originally known, from 1986 to 1998, as Sounds of Silents, the series was renamed Duck Soup Cinema in 1999. Recreating the movie theatrical experience of 90 years ago, Duck Soup Cinema is now one of the longest-running, continuous silent movie series in the Midwest. Duck Soup Diary is my attempt to both document and advertise this unique and important event combining live performance and historical revival.

DIRECTOR: F.W MURNAU/1927

The second of two special 2017/18 Duck Soup Cinema offerings, presented without vaudeville entertainment but still featuring live accompaniment on the peerless Grand Barton Organ, German Expressionist director F.W. Murnau’s first Hollywood movie, made for Fox Films in 1927, received a sterling Saturday, March 17th exhibition in a theater that opened just a few months after the film’s initial release 90 years ago. Subtitled A Song of Two Humans, Sunrise tells the story of a once happy and prosperous farmer (George O’Brien), from an idyllic riverside homestead, who is tempted by a vacationing vixen of the ‘vamp’ order (Margaret Livingston) into piecemeal selling off his farm and then murdering his loving wife (Janet Gaynor) in order to join his ill-gotten fortune with the evil temptress for a life of sin in the big city. A “simple story, masterfully told”, as I recall the capsule review contained in my youthfully much pored-over copy of Leonard Maltin’s Film Guide, this all-time masterpiece of the silent screen was revolutionary in its visual storytelling technique for its day, utilizing camera movement, lighting compositions, set design, miniatures, and eye-popping process effects (back when ‘effects’ actually were “special”) that remain as impressive and moving as when the on-screen dawn first literally rose on Sunrise’s near-century ago debut.

The second of two special 2017/18 Duck Soup Cinema offerings, presented without vaudeville entertainment but still featuring live accompaniment on the peerless Grand Barton Organ, German Expressionist director F.W. Murnau’s first Hollywood movie, made for Fox Films in 1927, received a sterling Saturday, March 17th exhibition in a theater that opened just a few months after the film’s initial release 90 years ago. Subtitled A Song of Two Humans, Sunrise tells the story of a once happy and prosperous farmer (George O’Brien), from an idyllic riverside homestead, who is tempted by a vacationing vixen of the ‘vamp’ order (Margaret Livingston) into piecemeal selling off his farm and then murdering his loving wife (Janet Gaynor) in order to join his ill-gotten fortune with the evil temptress for a life of sin in the big city. A “simple story, masterfully told”, as I recall the capsule review contained in my youthfully much pored-over copy of Leonard Maltin’s Film Guide, this all-time masterpiece of the silent screen was revolutionary in its visual storytelling technique for its day, utilizing camera movement, lighting compositions, set design, miniatures, and eye-popping process effects (back when ‘effects’ actually were “special”) that remain as impressive and moving as when the on-screen dawn first literally rose on Sunrise’s near-century ago debut.

pre-show organist Glenn Tallar

feature organist Clark Wilson

Bridging that gap of several succeeding generations, both in terms of history and entertainment, Overture Center’s Capitol Theater remains downtown Madison, WI’s best venue for recreating the spirit of the silent film era. And entering the theater from the ornately modern-yet-classical foyer and lobby, the expert exercise of the Capitol’s Grand instrument fifteen minutes before the film’s showing came courtesy of guest organist Glenn Tallar, presently hard at work on the Barton’s on-going restoration, who provided an always welcome medley of popular musical standards from the period. The spell of yesteryear now complete, triumphantly-returning organist Clark Wilson once again assumed the musical reins of the “perfumed twilight of this magnificent electric pleasure dome” with a meticulously researched and minutely transposed film-length organ score, based on Sunrise’s original sound-on-film Fox Movietone score-and-effects track, specially assembled and composed by the preeminent Erno Rappe (1891 – 1945).

A true feast for the eyes and ears unfolded to spellbinding effect over the next two hours, with a brief (and indeed suspenseful) break occurring when the drama’s tidal pull threatened to turn once more towards the tragic. Balancing tragedy and comedy, and then tragedy and triumph, throughout its 100-minute running-time, Sunrise gains immeasurably from both expert theater projection and proper musical setting, making the 35mm print of Duck Soup’s admirable presentation a rare treat to behold.

Reminding this viewer precisely to what Norma Desmond of Billy Wilder’s Sunset BLVD. (1950) was referring when wistfully terming films of the 1920s “BIG”, Sunrise augments its story’s involving yet melodramatic underpinnings to visually accentuate and atmospherically underscore realistic human behavior and emotions. From The Man’s stiffened, stalking gait gradually loosening and gracefully resolving to the mid-film’s delightful Peasant’s Dance, to The Woman From The City’s sensual hip gyrations contrasted with The Wife’s natural and unaffected shyness (all of the characters in screenwriter Carl Mayer’s “photo-play” are referred to by their “types” as opposed to their names, so as to retain their symbolic and universal qualities; though lip-readers may be able to pick out The Wife’s first name when The Man visibly “shouts” it repeatedly over the flooded stream by lantern-light towards the end), the big-screen viewing with an appreciative audience certainly amplifies the humanistic qualities of this light-projected dream of sight and sound.

The oppressive weight of the film’s opening coda, where the husband is driven to contemplate murdering his wife over still-morning waters, gives way to a pressure release of joyous companionship overstream in the big city, where bustling street-scenes (magnificently accomplished by rear-/front-projection) and vivid comic interludes at a barbershop (the husband’s shaggy hair and dissipated overgrowth of whiskers shorn to reveal a rather happy and innocent-looking young man), a portrait studio (a sympathetic photographer captures a romantically-candid moment between husband and wife), and a magnificent carnival-setting dancehall (which besides delightfully featuring the aforementioned Peasant’s Dance, also includes the husband’s clever capturing of a drunken pig!) complete a most memorably eventful day.

The day closing on near-tragedy, as fate threatens to turn the husband’s initial ill-intentions towards fruition — the wife lost in a truly terrifying storm — fortunately resolves to the title vision of a new dawn, as husband and wife symbolically embark on a screen-processed sunray of future wedded bliss.

Like the screen and organ further resolving from light and ambience to suddenly finding oneself among other dazzled audience members, gathering heavy coats and deepened thoughts after a two-hour screen-and-sound reverie, seeing Sunrise at Duck Soup Cinema was certainly among my more personally memorable evenings of theater-going. I sincerely hope everyone reading this last sentence will make it out for Duck Soup’s final season-showing of Buster Keaton in his first film as writer, director, and star, Three Ages: such exhibitions are rare and priceless, but fortunately this one is coming up in less than a week (April 7th, at 2 and 7PM) for a mere 7 bucks; the comedy and terror, the thrills, spills, and chills of yesteryear making your hard-earned, silent-era “nickel” well worth the price of admission!

co-cameraman Karl Struss filming Sunrise (1927)