Acclaimed Documentary Tells the Unlikely Tale of how Film Survived at Earth’s End

DIRECTED BY BILL MORRISON/2017

STREET DATE: OCTOBER 31, 2017/KINO LORBER

1978, Dawson City (near the Yukon Territory). A remarkable discovery was made. Nestled in the forgotten permafrost, preserved well beyond their years and against all odds, they were uncovered. People. Thousands of them. Black and white. Thousands of people from many walks of life, some acting, some playing, some just doing their jobs. Who are they? And why were they hidden away for so long?

1978, Dawson City (near the Yukon Territory). A remarkable discovery was made. Nestled in the forgotten permafrost, preserved well beyond their years and against all odds, they were uncovered. People. Thousands of them. Black and white. Thousands of people from many walks of life, some acting, some playing, some just doing their jobs. Who are they? And why were they hidden away for so long?

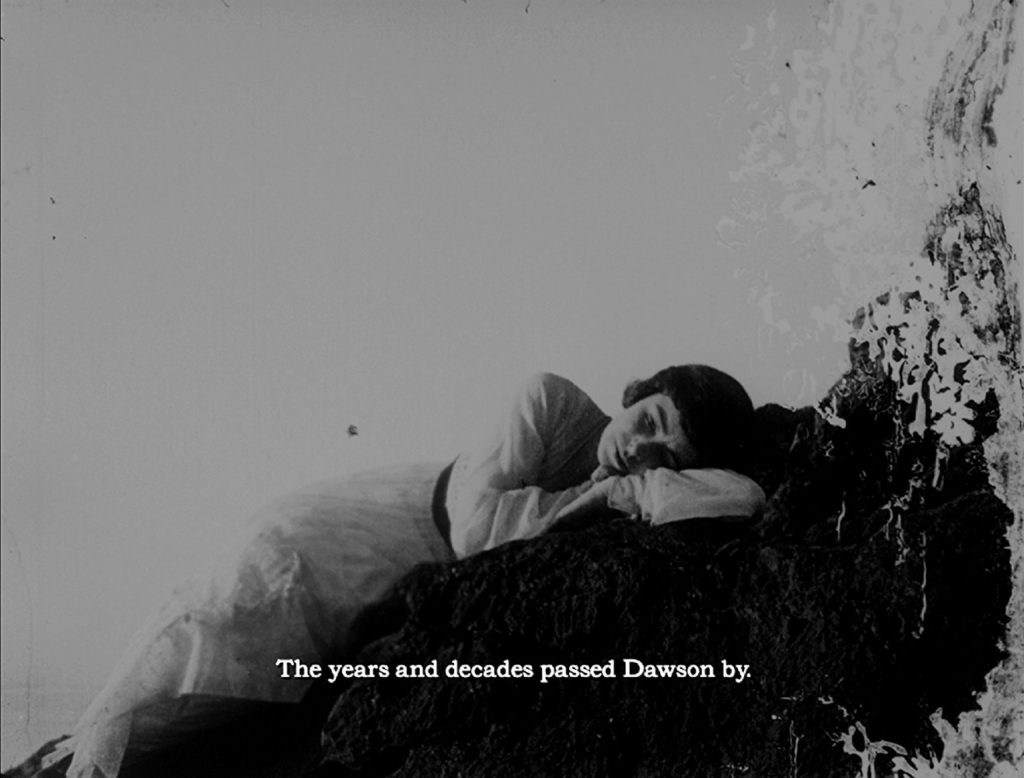

A brutal commonality: They are deteriorating, and their world right along with them. Not “their world”, strictly speaking. Who, when on film, has any say over where or especially when they are seen? A rhetorical question, of course; the answer being none. Not the commoners of the many vintage forgotten newsreels, not the actors playing roles in the earliest of early silent narratives. Not the “actuality” subjects awaiting trains or leaving the factory, not the 1919 White Sox, forever condemned for throwing the World Series. None of them are spared the natural deterioration that eventually eats away their remaining likenesses. The only question is, how long can this certain death-after-death be staved off?

Enigmatic by design, Morrison’s film, chronicling the early years of a desolate Alaskan gold mining town, is nearly silent, with a minimalistic original score by Alex Somers.

These are the people of the Dawson City Film Find. Each and every one of these celluloid ghosts share another commonality, this one not so brutal as it is miraculous: The fact that the nitrate film reels containing them didn’t burn up along the way to their recovery. Up until the early 1940s, all movie film was frighteningly susceptible to such an ashy fate. And even when it works as advertised, not combusting, the brash clickety-clacks of a projector pulling exposed old-time filmstock through its own gate can’t help but evoke fire. This, as the heat of the bulb itself ever threatens to ignite the supremely volatile celluloid. It all very much harkens to an historic truth that’s also the tag line: Film was born of an explosive.

Such fire and ice collide like light and darkness in filmmaker Bill Morrison’s (Decasia) unique documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time. Enigmatic by design, Morrison’s film, chronicling the early years of a desolate Alaskan gold mining town, is nearly silent, with a minimalistic original score by Alex Somers. Along the way, many brief text captions dissolve in and out, briefing we the viewers on the time, place, history and technology that allowed for such a disintegrated and withered cache of early early cinema to survive at Earth’s end, in spite of itself.

*****

1897, France. The Lumiere Brothers premiere the first public exhibition of motion picture technology.

Across the globe, in the farthest corner of Alaska, a gold rush has given birth to the ice-capped town of Dawson City.

Overrun with hopeful prospectors, the real gold soon proved not so much to buried them thar hills as in the nitrate on the reels of celluloid that showed in town. After all, the disheartened and ever-optimistic alike needed, sometimes achingly, for amusement. And if that newfangled photo-chemical process and mechanism of “moving pictures” wasn’t their thing, or if the theater that showed them had burned down, as it did several times, there was also the old standbys: bars, restaurants, gambling joints and prostitution. According to the film, Donald Trump’s grandfather was among the wealthy profiteers of the diggers’ downtime. And as the song never went, “Frozen Time/One last call for alcohol/So finish your whiskey or beer/Frozen Time/You don’t have to go home but you can’t stay here…”

Dawson City, back then.

The newfangled invention of the moving picture, still realizing its place as a narrative entertainment medium, found its way into the icy mix. Being a remote town on the edge of nowhere, Dawson was ruled by the film distributors to be the end of the line for the celluloid reels. The edict was, Do Not Send Them Back. Keep Them. Even the proper owners of the film itself, those who made it their business to make money from this contraption of light and shadow, had no use for old movies. “They’d run their course”.

The recollection that the small, ever-humble Dawson City burned to the ground each year for at least six years, prompting the populace to Rebuild! Rebuild! Rebuild! is a testament to their survivalist perseverance, but perhaps also an unintended rebuke of today’s comfortably disposable society. No condemnation is ever uttered, though the implication that 533 cans of vintage silent movies should be tossed into the Yukon River and forgotten can’t help but resonate with the ugly contemporary default on silent movies, contemporary movies, film history, and history itself. “Old is bad. Forget it.”

And every time a major studio lets a cinematic piece of its own heritage (our own heritage) die, this primitive edict is echoed.

*****

2017, Cinephilia. Made with the intent to entrance, Bill Morrison, this not being his first foray into disintegrating film history, may’ve, may’ve overreached, if only slightly with Dawson City: Frozen Time. There’s little debate that the implementation of clips of the recovered films of the world gone by, in their states of eerie decay, go a long way to cultivate an enigmatic atmosphere. Morrison’s silent narrative is ghostly in its text presence, slowly on and gone while making unlikely connections across time and tide, is never not intriguing. But it’s own prescribed stillness – it’s frozen quality – are just enough to keep one foot in a permafrost all its own. Hence, this is a very good movie, just not quite the brilliant spark Morrison was clearly ruminating to create.

Blu-ray bonus features are plentiful, reflecting Kino Lorber’s rightful pride in this title. There’s an interview with Morrison, a postscript on the film, the trailer, and a decently sized booklet with essays by Lawrence Weschler and Alberto Zambenedetti, well worth reading. The main attraction, though, is an hour-plus of transferred Dawson City film reels. Representative of the find itself, the included short films and fragments range from news reels (some oddly cheeky) to early narrative shorts by still-remembered filmmakers, including D.W. Griffith. To not include any of this material would’ve been tantamount to sin. To actually have included it is a film/history/film history buff’s own little bliss.

Dawson City: Frozen Time is the ever-rare project bold enough to reach far in the interest of uniquely weaving the disparate threads of life’s experiences. And, to some noteworthy degree, it most does. Morrison’s ambitious film admirably reaches out to cinephiles with the radiant allure that film, tactile and fragile as ever a thing could be, is the magical and mysterious key to a certain immorality, even amid much death.

Or, as the song goes, “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end…”