A Moving Story of Women Resisting Religious Oppression in Colonial India

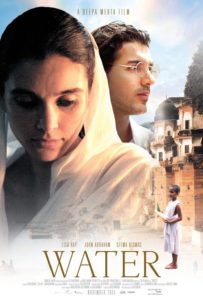

#52: WATER (2005)/HINDI, WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES

DIRECTOR: DEEPA MEHTA

It might have been nice to end this project on a light, fun film, something like Wayne’s World or The Edge of Seventeen. But it’s more fitting, really, to end my #52FilmsByWomen challenge with a movie like Water – a movie concerned with the rights of women and girls, and made by a female director who has had to overcome her share of opposition in filmmaking. What kind of opposition? Deepa Mehta’s 1996 film Fire, which portrayed a same sex relationship between two Indian women, was met with violent protests that included burning down a movie theater. In 2000, when Mehta started work on Water, the third of her Elements Trilogy (following 1998’s Earth), protesters destroyed the film’s sets. Production was shut down and the film was postponed until 2005, with shooting relocated from India to Pakistan.

It might have been nice to end this project on a light, fun film, something like Wayne’s World or The Edge of Seventeen. But it’s more fitting, really, to end my #52FilmsByWomen challenge with a movie like Water – a movie concerned with the rights of women and girls, and made by a female director who has had to overcome her share of opposition in filmmaking. What kind of opposition? Deepa Mehta’s 1996 film Fire, which portrayed a same sex relationship between two Indian women, was met with violent protests that included burning down a movie theater. In 2000, when Mehta started work on Water, the third of her Elements Trilogy (following 1998’s Earth), protesters destroyed the film’s sets. Production was shut down and the film was postponed until 2005, with shooting relocated from India to Pakistan.

Nevertheless, Mehta persisted. Each of her Elements films exposes ways in which religion has been used to exploit, oppress, and deny human rights, particularly to women. Mehta is Indian born but moved to Canada in her 20s. Hinduism is the religious context for her films, but I couldn’t watch Water without drawing parallels to the way that religion has operated in the Western world, and the heavy toll its misuse has exacted on women and girls.

“One less mouth to feed. Four saris saved, one bed, and a corner is saved in the family home. There is no other reason you are here. Disguised as religion, it’s just about money.”

Water follows three female protagonists, although 7 year old Chuyia (Sarala Kariyawasam) is most central to the story. The year is 1938 and Chuyia is already married, although she still lives with her parents. When her husband takes ill and dies, Chuyia finds herself a child widow in a culture in which widows have few rights and limited choices. They can die with their husbands, marry their husband’s younger brother, or live a life of poverty and chastity. Chuyia’s choice is made for her. Her head is shaved, her colorful clothes are replaced by white garments (the traditional color of mourning in India) and she’s placed in an ashram with other widows who survive primarily through begging.

Water follows three female protagonists, although 7 year old Chuyia (Sarala Kariyawasam) is most central to the story. The year is 1938 and Chuyia is already married, although she still lives with her parents. When her husband takes ill and dies, Chuyia finds herself a child widow in a culture in which widows have few rights and limited choices. They can die with their husbands, marry their husband’s younger brother, or live a life of poverty and chastity. Chuyia’s choice is made for her. Her head is shaved, her colorful clothes are replaced by white garments (the traditional color of mourning in India) and she’s placed in an ashram with other widows who survive primarily through begging.

Chuyia is a spirited little girl who doesn’t accept her new circumstances without a fight. She is fortunate to find a few friends among the widows: the ancient “Auntie” Patiriji (Vidula Javalgekar), who still dreams of the sweets she enjoyed at her wedding feast, when she a child like Chuyia; Shakuntala (Seema Biswas), a deeply devout and somber widow; and Kalyani (Lisa Ray), a beautiful young widow who lives apart from the others and becomes Chuyia’s playmate. Kalyani is the only widow whose hair is not shorn, and there’s a grim reason for that, and for her isolation. Madhumati (Manorma), the head of the ashram, pimps Kalyani out to wealthy men in the community. Although the other widows rely on the income that Kalyani provides they also look down on her as unclean.

Water is set against the background of Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for Indian independence, bringing with it a more progressive version of Hinduism. In defiance of the community, Kalyani falls in love with a young political activist, Narayan (John Abraham) and accepts his offer of marriage. Shakuntala has spent her life in irreproachable religious devotion, but struggles increasingly with doubt. As for Chuyia, she retains her bright spirit, but the role to which Kalyani has been assigned hangs ominously over her future.

Water is set against the background of Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for Indian independence, bringing with it a more progressive version of Hinduism. In defiance of the community, Kalyani falls in love with a young political activist, Narayan (John Abraham) and accepts his offer of marriage. Shakuntala has spent her life in irreproachable religious devotion, but struggles increasingly with doubt. As for Chuyia, she retains her bright spirit, but the role to which Kalyani has been assigned hangs ominously over her future.

All three of the central performances in Water are stunning. Kariyawasam gives an emotionally nuanced performance, especially for one so young. Her smile lights up the screen, but Chuyia’s tantrums are as convincing as her joy. Lisa Ray is luminous, and makes us believe that Kalyani has found a way to be “like the lotus, untouched by the filthy water it grows in”. Biswas’s performance as Shakuntala is perhaps the most powerful of all, as a woman who can’t make sense of the suffering to which society has consigned her and her sister widows. Shakuntala begins to rebel in small ways, but eventually takes costly stands against Madhumati for the sake of both Kalyani and Chuyia.

There was a point in Water’s narrative at which I thought the story would have a happy ending, but I was wrong. There’s no cheap comfort in Water, yet the movie is saved from being pure tragedy by Shakuntala. In two potent scenes she asks why widows must suffer as they do. A Hindu priest can only quote the sacred texts which prescribe poverty and chastity for widows. Later, Shakuntala asks Narayan, “Why are we widows sent here? There must be a reason for it.” Narayan offers a damning indictment of the system in which the widows are bound: “One less mouth to feed. Four saris saved, one bed, and a corner is saved in the family home. There is no other reason you are here. Disguised as religion, it’s just about money.” Shakuntala’s doubts and confusion shift to anger and a courage that drives her to an act of true heroism that will, she hopes, save Chuyia from Kalyani’s fate.

There was a point in Water’s narrative at which I thought the story would have a happy ending, but I was wrong. There’s no cheap comfort in Water, yet the movie is saved from being pure tragedy by Shakuntala. In two potent scenes she asks why widows must suffer as they do. A Hindu priest can only quote the sacred texts which prescribe poverty and chastity for widows. Later, Shakuntala asks Narayan, “Why are we widows sent here? There must be a reason for it.” Narayan offers a damning indictment of the system in which the widows are bound: “One less mouth to feed. Four saris saved, one bed, and a corner is saved in the family home. There is no other reason you are here. Disguised as religion, it’s just about money.” Shakuntala’s doubts and confusion shift to anger and a courage that drives her to an act of true heroism that will, she hopes, save Chuyia from Kalyani’s fate.

Water is a gorgeous, gut wrenching film. Lush colors and beautifully shot performances make the painful aspects of the story feel that much heavier. Deepa Mehta ends Water with a statistic on the plight of widows in modern day India. The laws are more equitable, but religious tradition is slow to change. Indeed, as a more conservative Hindu nationalism grows stronger in India, the plight of widows may worsen in the years ahead. But as I said at the top of this review, the use of religion to oppress women is not a uniquely Hindu phenomenon. I’ve spent years studying the history and varieties of my own faith tradition (Christianity) and we’ve got plenty of our own problems with gender inequality.

This was the perfect movie on which to end the #52FilmsByWomen project: a fine film, about things that really matter, from a female director who was willing to face hell or high water (or more precisely, riots and arson) to see her visions on the screen. May Deepa Mehta’s tribe increase.