Boffo! Catching up with the Biggest Ticket Sellers in Cinema History

June 2016: Vanity Fair runs the article “2016 is on Track to Be Hollywood’s Worst Year for Ticket Sales in a Century.”

December 2016: The Hollywood Reporter writes, “2016 Box Office Revenue Hits $11.17B for Another Record Year.”

So…what happened here? Did Rogue One singlehandedly boost the entire film industry from one of its worst years to one of its best? Jyn Erso and her crew should never be underestimated, but we can only credit them with successfully stealing the Death Star plans and winning the yearly box office. The weird-but-true explanation is that both headlines are accurate.

Here’s the list of the highest grossing movies of all time in the United States:

- Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015)

- Avatar (2009)

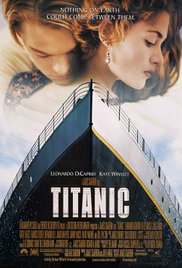

- Titanic (1997)

- Jurassic World (2015)

- Marvel’s The Avengers (2012)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016)

- Finding Dory (2016)

- Beauty and the Beast (2017)

- Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999)

The list is stacked with recent releases, including one that just made the list in the last week. The twist: The Force Awakens actually sold fewer tickets (88 million) than Titanic (94.5 million tickets). The average ticket price has almost doubled in the last 20 years, which means Hollywood still breaks records even while the number of sales declines. When you adjust the list for inflation (a.k.a. ranking movies based on the number of tickets sold), the top 10 looks radically different in reflecting the real number of paying customers who’ve actually witnessed the movies they paid to see on the big screen:

- Gone with the Wind (1939)

- Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope (1977)

- The Sound of Music (1965)

- E.T. The Extraterrestrial (1982)

- Titanic (1997)

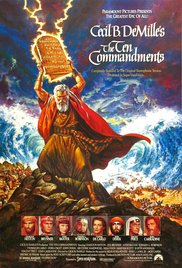

- The Ten Commandments (1956)

- Jaws (1975)

- Doctor Zhivago (1965)

- The Exorcist (1973)

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937)

Without accounting for the numerous re-releases of each of these films (Gone with the Wind was re-released at least ten times, each at differing prices, as were in lesser re-releases Snow White, Star Wars, The Sound of Music, The Ten Commandments, Jaws, The Exorcist, and Doctor Zhivago), the adjusted list skews much older, and shares only one title with the first. Drunk with power in choosing this month’s Film Admissions, I decided this was the list I wanted to focus on. These are the movies the most Americans have made time for in history, which means they have made some of the most lasting impressions on the cultural consciousness. Popularity and artistry, while not synonymous, are not mutually exclusive either, which means we’re left with a list of 100 movies with at least something to admire in each of them. Here’s what the critics at Zekefilm have found to love and loathe in those films in the Top 100 that we have somehow left unseen.

P.S. While my easily-jumpy nature means I may never get around to The Exorcist, I hope to make it through the rest of the list like my fellow critics Paul Hibbard and Dean Treadway (who is now just a Finding Dory shy of all 100.) They are #FilmCriticGoals.

– Taylor Blake

Gone with the Wind (#1)

(1939, Selznick International Pictures, d. Victor Fleming, et al)

by Max Foizey

Arguably the biggest hole in my film viewing history, just hours before this writing I had not seen Gone with the Wind, Victor Fleming and David O. Selznick’s epic adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s “Story of the Old South.” The story takes place during the United States’ civil war and reconstruction, deep in a romanticized vision of America’s South that never really existed. The opening credits include a passage that states this was a time of “master and slave” that is now only a “dream remembered.” In today’s parlance I’d describe this idea as problematic.

Arguably the biggest hole in my film viewing history, just hours before this writing I had not seen Gone with the Wind, Victor Fleming and David O. Selznick’s epic adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s “Story of the Old South.” The story takes place during the United States’ civil war and reconstruction, deep in a romanticized vision of America’s South that never really existed. The opening credits include a passage that states this was a time of “master and slave” that is now only a “dream remembered.” In today’s parlance I’d describe this idea as problematic.

After the opening overture we are introduced to Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) as she’s complaining that all this talk of war is really harshing her mellow. She wants to party and flirt with all the cute guys! Can’t everyone drop all this war nonsense and remember what’s important? Somebody please put that Don Henley song on the record player, because All She Wants to Do is Dance.

A vision in green, Scarlett gives new meaning to the term petulant as she soaks up the adoration of most of the eligible bachelors around her. She has her eyes on Ashley (Leslie Howard), who has fallen for Melanie (Olivia de Havilland) much to Scarlett’s dismay.

We are introduced to Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) at the bottom of the stairs of Tara, the lush O’Hara estate, as he bemusedly exchanges barbs with Scarlett, the girl wearing the largest hat. She dismisses the man from Charleston and they part ways, for now.

On the brink of war, Scarlett makes a snap decision accepting a marriage proposal from Melanie’s brother Charles, a bumbling oaf she doesn’t care for. Scarlett cries her way through the ceremony but has trouble summoning tears months later after Charles dies of pneumonia during his service. Mourning doesn’t suit her.

If this were set in modern day, Scarlett would spend her time taking 1,000 selfies a day in front of her mirror. Hashtag blessed. Are we supposed to like Scarlett O’Hara? Identify with her? O’Hara reminds me a bit of Anna Karenina, another of literature’s self-possessed debutantes.

Rhett and Scarlett’s paths cross time and again, their connection and love story deepening. Soon we’re headed toward an intermission as Atlanta burns with the fires of hell, the years of war soon to make their mark on their lives.

I watched this film over two nights and truly the tone of the film changes after the intermission. Scarlett is, at least for a time, a changed woman and Rhett decides to give their relationship a try. I wonder if they’ll live happily ever after? I wonder if America will?

Clark Gable brings Rhett Butler to life with a charming swagger, sly humor, and toward the end, unexpected tenderness. Vivien Leigh plays Scarlett O’Hara larger than life in every scene. This is a character who is all or nothing; she never has a calm moment. By contrast, Olivia de Havilland’s Melanie is the picture of stoicism. It’s a great performance.

As Mammy, Hattie McDaniel is awesome, referring to the family in her charge as “white trash” and constantly muttering under her breath her frustrations. A good friend of Gable, McDaniel won an Academy Award for her performance, the first African-American actress to do so, something that (ridiculously) wouldn’t happen again until Halle Berry’s win for Monster’s Ball in 2002.

Gone with the Wind completely glosses over racial issues, imagining that African-Americans had no problem with slavery and would choose to continue to be in service of whites even after being offered forty acres and a mule. To a modern viewer, it’s shocking to see depictions of slavery without anyone raging against it. It’s fair to say Gone with the Wind is a more accurate time capsule of the age in which it was made more than the age it depicts.

The focus here is Scarlett and Rhett’s doomed love and the doomed future of the American South. I took Scarlett’s refusal to accept Rhett’s rejection at the close of the film as a metaphor for the South’s refusal to accept the North’s victory. Gone with the Wind is heavy on symbolism and metaphor, a requiem for a period of time that might not deserve one. Frankly my dear, we don’t give a damn.

Gone with the Wind features a story and characters you could dissect for years, an excellent cast, incredible production design, and Max Steiner’s famous score, which you’re no doubt familiar with even if you haven’t seen the film. Steiner’s score is lovely throughout, with “Tara’s Theme” being among the finest pieces of film music ever composed. 1939 stands as one of the best years in the history of film and with scene after scene of breathtaking beauty in vibrant technicolor, Gone with the Wind is one reason why it remains as such.

Titanic (#5)

(1997, Paramount Pictures/20th Century Fox/Lightstorm Entertainment, dir. James Cameron)

by Justin Mory

As might be clear at this point in the feature, this is my reaction to a first-time viewing of Titanic, which I narrowly managed to avoid for our Admissions article on Best Picture Winners last year. And with 3 hours, 14 minutes, and 49 seconds of period costume romance, ship-sinking, and young Leo to sit through, I obviously had not one reaction, but several. Here are a few points, some more obscure or irrelevant than others, but, well, I had to mark the time somehow:

As might be clear at this point in the feature, this is my reaction to a first-time viewing of Titanic, which I narrowly managed to avoid for our Admissions article on Best Picture Winners last year. And with 3 hours, 14 minutes, and 49 seconds of period costume romance, ship-sinking, and young Leo to sit through, I obviously had not one reaction, but several. Here are a few points, some more obscure or irrelevant than others, but, well, I had to mark the time somehow:

- From its first mention, “Titanic” is referred to during the treasure hunting sequence and during its ill-fated voyage in flashback without the speech article “The.” Along with the plot’s bombardment of history trivia, and its bottomless reservoir of minutiae-level detail, my initial resistance to the film’s intimidating running time was effectively overcome as I always enjoy a good grammar lesson.

- Dialogue like “So this is the ship that they say is unsinkable?” and “I’m a strong swimmer” does tend to tip a screenwriter’s hand a bit heavily in the foreshadowing and dramatic irony department. However, shots continually emphasizing Titanic’s overwhelming “bigness” receive a nice counterpoint when later dialogue takes a more sophisticated turn over Freudian implications of scale and size.

- That DiCaprio’s character should come from “Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin” is a point of sensitivity for this viewer considering I also hail from Wisconsin; which, as a location, usually suggests through screenwriting laziness that a character comes from “nowhere in particular”. But as the character, Jack Dawson, does mention “ice fishing”, I felt reassured that someone working on the film had at least a general awareness of where Wisconsin is located on a map.

- I also felt reassured that the film’s makeup department did not attempt to bleach Kate Winslet as Rose’s naturally and charmingly off-white teeth but did add a marked yellowish line under the upper lip of Bernard Hill as Captain Smith’s impressive white mustache and beard. Not only did 1912 not share our obsession with teeth-whitening, but a nicotine stain – on the facial hair of a presumed pipe or cigar smoker – could then be worn as a badge of professional honor.

- I appreciated Gloria Stuart’s performance as the elderly Rose up to the point where she perilously climbs the steps of the ship’s railing to throw overboard the Heart of the Ocean necklace – which she had apparently kept 85 years without telling anyone she possessed it. I didn’t object to her dropping the jewel into the ocean or the fact her character kept it so long without telling anyone, but mostly to a 101-year-old doing the centenarian equivalent of gymnastics on the cold prow of a storm-tossed vessel in her nightshirt.

For a further observation, cutting the scene where Leo as Jack teaches Kate as Rose to “properly spit” might have shaved a couple minutes off what some might call the film’s “oppressive length”, but then we wouldn’t have the grand pay off where she so effectively expectorates in Billy Zane as imperious fiancee/financier Cal Hockley’s face. As for the rest, it would take a much (much) longer review to mark every impression, but suffice it to say that with James Cameron and Paramount Pictures making over a billion dollar return on their mere 200 million dollar investment, audiences got their money’s worth: that ship certainly did sink. (Eventually.)

The Ten Commandments (#6)

(1956, Motion Picture Associates, Inc., d. Cecil B. DeMille)

by Taylor Blake

Holy cow, this movie was long—pun intended. I’ve already admitted I’ve yet to complete this Top 100 list, but I already know The Ten Commandments won’t make my personal top ten.

Holy cow, this movie was long—pun intended. I’ve already admitted I’ve yet to complete this Top 100 list, but I already know The Ten Commandments won’t make my personal top ten.

Despite its release in an era more embracing of Judeo-Christian values, I was surprised to find The Ten Commandments followed the Bible’s account about as religiously as 2014’s retelling, Exodus: Gods and Kings—that is to say, not very well. Exodus was met with a meh consensus and made more headlines for its racially-inaccurate casting (another overlapping feature of these two films), and tried to sell itself as an action movie to the general masses. There’s a reason The Ten Commandments made this list instead of Exodus: It knows its audience much better.

While Ridley Scott’s Exodus seemed to prioritize the box office, Cecil B. DeMille tells his story with reverence. Commandments begins with an introduction from DeMille himself explaining that the movie takes some creative liberties to fill in the gaps, citing that some of its plot points come from ancient historians. While it’s an odd way to start a picture, its attention to the most faithful audience members literally paid off.

And this must have covered a multitude of sins for moviegoers in 1956. Because in addition to the Biblical scenes of baby Moses in a basket and the Exodus, DeMille brings us a number of brand new subplots: A romantic triangle between Moses (Charlton Heston), Ramses (Yul Brynner), and Egyptian princess Nefretiri (Anne Baxter); another romantic conflict between Joshua (John Derek), Lilia (Debra Paget), and two greedy Egyptian overlords; Prince Moses’s conquering of other lands; dance tributes from those other lands—much like the movie itself, this list of subplots Never. Seems. To. End.

It takes hours to even reach the delivery of the Ten Commandments, which is a scene that explodes with countless extras, colorful costumes, and special effects that haven’t aged well. See: the literal explosion when Moses throws the tablets onto the golden idol. Commandments suffers from extreme bloat, which is especially frustrating because its best moments are not the grandiose speeches and stagey set pieces. The true achievements are when it shows the human impact: A woman giving birth in the back of a cart while leaving Egypt, families wailing as the Angel of Death takes their firstborns, slaves’ deaths at work, families tripping across the Red Sea. Commandments tells its story best when individualizing those extras, not maxing the screen out with spectacle.

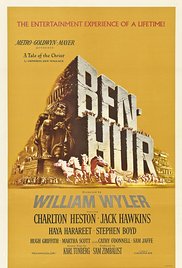

Ben-Hur (#14)

(1959, MGM, d. William Wyler)

by Robert Hornak

Here’s the real admission: I honestly didn’t know this was a Jesus movie. I’d seen the bit where an “anonymous hand” gives thirsty Heston a ladle of water, but I’d no idea the extent to which the movie is really the Gospels from the wings. The breadth of Christ’s manger-to-grave and beyond is seen from the vantage of a popular Jewish prince, Judah Ben-Hur (Heston), as he tangles with the increasingly oppressive Roman government in Jerusalem, occasionally crossing paths with the divine in scenes that play like a biblical Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. Heston, who was Moses only three years before, graduates into the New Testament and brings every bit of his big-toothed gravitas to bear as the de facto leader of the Jews against his own best friend, Messala (Stephen Boyd), a Roman tribune, whose determination to corral the locals into Roman subjugation is as rigid as Judah’s fierce efforts to clip it to the quick, until all comes to horse-drawn blows in a chariot race that’s the template for, you know, every action movie chase scene you’ve ever seen.

Here’s the real admission: I honestly didn’t know this was a Jesus movie. I’d seen the bit where an “anonymous hand” gives thirsty Heston a ladle of water, but I’d no idea the extent to which the movie is really the Gospels from the wings. The breadth of Christ’s manger-to-grave and beyond is seen from the vantage of a popular Jewish prince, Judah Ben-Hur (Heston), as he tangles with the increasingly oppressive Roman government in Jerusalem, occasionally crossing paths with the divine in scenes that play like a biblical Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead. Heston, who was Moses only three years before, graduates into the New Testament and brings every bit of his big-toothed gravitas to bear as the de facto leader of the Jews against his own best friend, Messala (Stephen Boyd), a Roman tribune, whose determination to corral the locals into Roman subjugation is as rigid as Judah’s fierce efforts to clip it to the quick, until all comes to horse-drawn blows in a chariot race that’s the template for, you know, every action movie chase scene you’ve ever seen.

Heston is an effortless Atlas, letting the mammoth production sprawl across his shoulders while still letting slip a believably helpless facet to his usual loping, set-chewing persona. There’s even a couple of times when it actually seems like he’s not aware of the camera, testament perhaps to director William Wyler’s do-over sensibility. Wyler, as we learn again in Five Came Back, had a natural connection to not only the oppression of the Jews (he was Jewish, and his hometown was all-but-emptied by Hitler’s final solution), but to soldiers in the fray, lending a double-edged sword of veracity to Heston’s scenes as a warship’s galley slave. Wyler does some heavy rowing of his own, guiding the melodrama-heavy three-and-a-half hours toward an earned, heart-felt cinch-up of not only Judah’s friends-and-family plan, and not just the more general salvation of the world by the bit-part Savior, but nothing less than the raising of cash-strapped MGM from the dead.

The regal pageantry of the entire afternoon’s viewing is like the finest confection of every Technicolor Bible epic of the ’50s rolled into one, with the Earnest Knob cranked to XI, and pushing a back-bent faithfulness to the source material that’s been spoofed in everything from Life of Brian to Hail, Caesar!, but which here feels sacred enough to be respected without irony, and yet be-robed in its own grandiose bijou mythology enough to be cheered at a basic white-horse/black-horse level. It’s a movie that, for all of my life, made me chafe at the idea of its having won so many Oscars (11!) – but now that I’ve seen it, I can’t understand why anyone would begrudge it an extra two or three awards… forgetting, please, the Pentateuchal irony of best-actor Moses proudly accepting his golden statue.

Jurassic World (#24)

by Dean Treadway

I was mildly surprised to learn that, out of the top 100 adjusted-for-inflation moneymakers, there were only two titles I hadn’t seen. I was less surprised to learn they were two of the more recent smash hits: Pixar’s Finding Dory and Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World. Both hail from franchises whose popular charms still escape me, but I was not in the mood to revisit Pixar’s underwater world; Finding Nemo was, for me, a rare Pixar dud—laughless (except for occasional bright moments for Ellen Degeneres’ forgetful fish), preachy, and visually dull, so I reluctantly went with the dinosaur movie, The best I can say is that I didn’t despise it as much as I thought I might.

I was mildly surprised to learn that, out of the top 100 adjusted-for-inflation moneymakers, there were only two titles I hadn’t seen. I was less surprised to learn they were two of the more recent smash hits: Pixar’s Finding Dory and Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World. Both hail from franchises whose popular charms still escape me, but I was not in the mood to revisit Pixar’s underwater world; Finding Nemo was, for me, a rare Pixar dud—laughless (except for occasional bright moments for Ellen Degeneres’ forgetful fish), preachy, and visually dull, so I reluctantly went with the dinosaur movie, The best I can say is that I didn’t despise it as much as I thought I might.

Going by director Colin Trevorrow’s debut feature, the phony-baloney time travel indie Safety Not Guaranteed, I could see nothing that could qualify this nascent filmmaker for the Jurassic World assignment—nothing, that is, beyond Trevorrow’s exuberant grab for the Spielberg crown (versed in goopy sentiment and rushing action, he obviously idolizes the director). So I guess Trevorrow did his job well enough; he steps out of the way and basically lets the film direct itself, in accordance with what the audience wants, which is more of the same.

So, after a series of disastrous results after the resurrection of dino DNA, the team behind this massive, ill-gotten experiment still haven’t learned their lesson, and now the titular theme park is back up and running. The park seems to be packed with ugly Americans who’ve miraculously gotten up off their lazy butts, gotten a passport, and trundled off to Costa Rica (yeah…right) to attend a park that’s definitely had its fair share of stomping. gnashing. bloody problems in the past. Bryce Dallas Howard, as the park’s harsh Operations Manager, is playing Queen Bitch here, in an unfair portrayal of a woman with power and drive. The film got a lot of flack for keeping her in high heels all throughout the antics required, but it’s equally amazing that her sharply coiffed hair and light-colored clothes barely get mussed throughout. Anyway, it’s a thankless, icy role.

Meanwhile, the ever-adored Chris Pratt manages to make an impression as a dinosaur trainer who slowly realizes he’s complicit in reducing his charges to slave labor. This was a part of the film I was rather impressed to see—one that has sympathy for these unique animals rather than just pure dread for them. Pratt adds some much needed personality to the film, particularly in its first half–unfortunately, he gets lost in the havoc-packed conclusion. But I liked that his character reminds us these dinosaurs are sentient beings peeved at being displayed for human entertainment (in this, Jurassic World reminded me both of the anti-Seaworld documentary Blackfish and of the amazing Ray Harryhausen masterpiece The Valley of Gwangi, where cowboys rope a Tyrannosaurus Rex and then lead it to its doom). I was impressed with the movie at least for giving us something substantive to consider amidst all the CGI foofaraw.

As with Jurassic Park, this film goes off the rails when focusing in on the kids that are forced to be part of the story, since this is basically a movie for kids. Here we have Howard’s two annoying nephews, played by annoying actors, who are sent off sans parents on a visit to their famous aunt’s park (yeah…right, again). After the teen brother finishes creepily eying every girl he sees, he’s forced to focus in on bonding with his even goofier and of course brainier younger sibling. In theme park tradition, they break away from the aunt (who, as Queen Bitch, has no time for them) and nab a rolling plastic-ball vehicle designed to roam amongst the free-range lizards. What maniac from the park’s planning team okayed this radically dangerous concept in the first place? The minute we see the kids piloting this lethal device, we absolutely know the dinos are gonna use it as a de facto soccer ball. This plastic prison thing is a lawsuit waiting to happen. The whole scene got my blood boiling not with intrinsic excitement, but instead with its bald implausibility and resultant tedium.

Of course, there’s a chubby villain here (Vincent D’Onofrio, doing his best with what he’s got) and we know he’s gonna get it in the neck for being pure, greasy evil. There’s also a pathetic, fat security guard who gets the “funniest” demise in the movie (just sitting there helplessly, his torso gets a big, sad chomp). Hollywood hates fat people, you know. Another disgusting aspect of Jurassic World is all of the product placement embedded in it. It’s endless (seriously, it goes on to the very final shots, and I know it’s supposed to be all meta and such, but it’s just irritating). At one shameless low point, the kids are watching a dinosaur show, and after a widely-applauded stunt, the older brother turns to the younger and yells “Now do you wanna see something really incredible?” and the little tyke screeches “Yeah!” We immediately cut to a long, lovingly-lit shot–clearly blueprinted by corporate wonks–of the gleaming white Mercedes SUV Howard drives throughout the film. Arrrgh. Just add a burly Sam Elliott voice-over, why doncha? This was more than enough to make me surely place Jurassic World into my “despise” column. Other than occasional moments (including that one effective jolt where the park’s official Shamu swooshes out of the water), Trevorrow’s test run for Spielberg glory rarely got my heart rate up, but it did make me bond with the once-scary raptors a little more. The humans, though, are still mostly a steaming bowl of wrong. Can we make one of these movies without those pesky varmints?

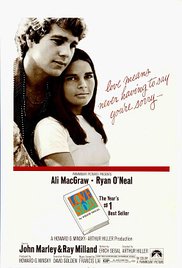

Love Story (#37)

(1970, Paramount Pictures, d. Arthur Hiller)

by Jim Tudor

What can you say about a 47-year-old-movie that died? This is a question that not many people ask anymore, seeing how director Arthur Hiller’s tragi-drama Love Story is, for all intents and purposes, culturally dead at this point. Is there a more obscure, passed over movie on this list of ours? (Never mind the entire top 100…)

What can you say about a 47-year-old-movie that died? This is a question that not many people ask anymore, seeing how director Arthur Hiller’s tragi-drama Love Story is, for all intents and purposes, culturally dead at this point. Is there a more obscure, passed over movie on this list of ours? (Never mind the entire top 100…)

Of course, it wasn’t always this way. A glorified made-for-TV weepie such as this doesn’t reside at number thirty-seven on the All Time Domestic Box Office Earners (Adjusted for Inflation) list without a zeitgeist nudge in its own time. For Love Story, that time was 1970. It’s a tale of a young couple swept up in amour fou, addressing class, broken families, adjusting career expectations in light of marriage, and finally death.

It’s no spoiler to say that Ali MacGraw’s Jennie doesn’t live to the end – the first line of the film is the hopeless inner pondering of Ryan O’Neal’s heartbroken Oliver, “What can you say about a twenty-five year-old girl who died?” The one-time athletic and wealthy Harvard man sits alone at an empty sports field in the melty, grey-snow throes of a typically dreary East Coast winter. The film’s thematic embrace of such tactile atmosphere of its Boston location is one of its great strengths, cementing the universality of the relational ups and downs of this solitary couple.

Another great strength is Ali MacGraw as the female lead. For this film to be effective, we must understand why Oliver falls for her. With her sharp demeanor and no-frills physicality, I admit to being resistant to this, wondering if this is another “manic pixie dream girl”, here and freely available to liberate our sad sack of a male lead. Though the dialogue has plenty of witty snap, Jennie’s supposed blue-collar perpetual swearing is strangely unbecoming when delivered from the mouth of MacGraw. Eventually, though, her famed inner radiance won me over (at least enough), just as it apparently won over so many others in her brief supernova of fame. She got one of the film’s seven, count ’em, seven Oscar nominations that year, and will live on every time her character’s famous and ridiculous line, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry”, is played back.

O’Neal is a different matter. Although he is said to have been the ninth choice actor to play the role, he too scored an Oscar nom and a leading man career, at least for a while. In retrospect, it’s interesting that the two films of his that live on with the most vibrancy are the ones which subvert his aspired-to leading man image that Love Story was utilizing: Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), and Peter Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? (1972). It’s in the comedic button of the latter film that he gets to skewer Love Story‘s famous tagline upon its being recited by Barbara Streisand. His reply of “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life.” is a reference both uproariously meta and increasingly lost to ages.

It’s not cool to like a film as earnest as Love Story, but that’s not why I haven’t warmed up to it. I actually love a good melodrama. But director Arthur Hiller, in adapting the popular novel by Erich Segal (whom actually wrote the screenplay first, only to novelize it when he couldn’t generate any interest for it as film), plays it quick, dour, and sometimes wooden. It’s not a long story (another anomaly on this list!), but it is a pretty bland no-frills time capsule that’s no longer particularly easy to love.