DIRECTED BY RICHARD A. COLLA/1972

STREET DATE: OCTOBER 18, 2016/KINO LORBER

First off, it’s a comedy, and one that happens not to be funny. Ever. It never even seems to be trying (unless you think, as the filmmakers clearly do, the sight of Reynolds and portly co-star Jack Weston going undercover as nuns is a riot). Usually, one can find something in a Weston performance to admire—some tiny mushmouthed line reading or vein-popping meltdown—but not here. He’s bored, and why wouldn’t he be? Though the Evan Hunter screenplay is based on an entry from his 87thPrecinct series (written under kick-ass nom de plume Ed McBain), the script never gears up. It’s tries, and fails, to create an intermingling omnibus of crime stories to torment this shaggy arm of the Boston police force.

It’s a comedy, and one that happens not to be funny. Ever. It never even seems to be trying (unless you think, as the filmmakers clearly do, the sight of Reynolds and portly co-star Jack Weston going undercover as nuns is a riot).

At one early point, with the camera plunked down in a drab, gray, overlit precinct set that makes you miss the shadowy charms of ’50s noir films, we start to notice the faint influence of Robert Altman as many characters wander in and out of the frame, talking over each other. But they’re not saying anything remotely clever, and the Altmanesque whiff is erased by uninventive camerawork and lazy acting. In the end, one is primarily reminded of a dry run for TV’s landmark cop comedy Barney Miller, though that expertly written and cast series did things right.

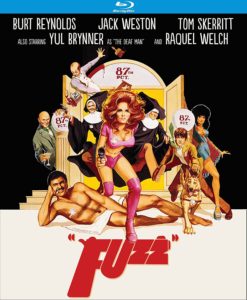

The main throughline here is an assassination/extortion scheme set up by a wealthy crime boss (Yul Brenner, unseen until the film’s more than half done). It’s a plot string that, by a disappointing climax, leaves us thinking “Well, what was that all about?” We also get a running “gag” with two drunk teenagers–one of them American Graffiti‘s Terry the Toad, Charles Martin Smith, slumming it—getting their jollies by setting homeless men on fire (among their victims is an undercover Reynolds, doing his own stunts, of course). By the way, I discovered that a rash of ’70s bum burnings were blamed on TV airings of the film, forcing the subplot to be trimmed in subsequent versions. Anyway, Reynolds is barely in the film. I suppose at this point, his superstardom hadn’t yet taken off. The filmmakers have clearly not gotten a bead on his good humor or charisma, so his presence lands as a meager adjunct to an unexciting ensemble (though the film’s poster cravenly includes a rendition of his controversial Cosmopolitan centerfold).

Same goes for Raquel Welch, an oasis of loveliness here who’s predictably treated like garbage as the new addition to the force, assigned to track down a park rapist in a fumbled yarn clunkily dropped in her brutal final scene (she notably refused to do a nearly nude scene, though the filmmakers shoehorned a glimpse of her shooting a bird at the audience while fixing up in the men’s room). Altman veteran Tom Skerritt, also working beneath his merit, is in the mix as a unctuous detective more concerned with bedding Welch than with solving cases (his literally undercover grappling with her in a park-set sting is painful to witness).

But mostly what we get is a badly-edited parade of lowlifes in that ugly precinct set–everything about this film is ugly–babbling about nonsense (much time is wasted on two grating, wise-cracking government employees assigned to paint the precinct walls; they cackle at the notion of a woman being put on hold during her molestation). There are glimpses of good ’70s-era actors—Bert Remsen, Charles Tyner, Brian Doyle Murray, Tamera Dobson, Dominic Chianese (in a blink-or-you’ll-miss-it appearance as a panhandler), and Peter Bonerz (as one of Brenner’s henchmen)–so at least I was entertained by that. Often, I watch ’70s films to just enjoy the look of the era’s urban settings but, here, the Boston setting is not used to any real advantage.

As for the Kino Lorber Blu-Ray itself, the scrubbed-up imagery is better suited for an overplayed VHS, where the grittiness would actually be enhanced. Included on the disc is a director’s commentary (why would you wanna listen to that?) and a much-too-kind Trailers from Hell segment hosted by screenwriter John Olson. In the end, the only thing I liked about the film is maybe its outrageously deceptive ad campaign and Dave Grusin’s funky title theme, though the rest of the score is strictly bad-TV-movie blather, which pretty much sums up the whole of Fuzz.