A Savory Italian Blend of Pulp Noir and Neo-Realism

DIRECTED BY GIUSEPPE DE SANTIS/ITALIAN/1949

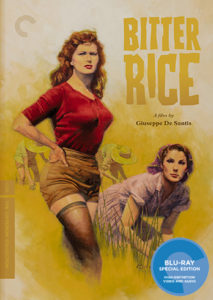

STREET DATE: JANUARY 12, 2016/CRITERION COLLECTION

Cinephiles and historians can (and do) debate about which postwar Italian movies were a “betrayal” of the intentionally cultivated neorealism movement. But more plainly, a case could be made that neorealism got tired of itself. Or, more readily, Italian neorealism had always, in different ways, allowed for more than just soul-searing tales set amid a world of bombed out rubble. How best to go about its mission of humanizing postwar Italy is a question that would fall upon its individual filmmakers.

Cinephiles and historians can (and do) debate about which postwar Italian movies were a “betrayal” of the intentionally cultivated neorealism movement. But more plainly, a case could be made that neorealism got tired of itself. Or, more readily, Italian neorealism had always, in different ways, allowed for more than just soul-searing tales set amid a world of bombed out rubble. How best to go about its mission of humanizing postwar Italy is a question that would fall upon its individual filmmakers.

Giuseppe De Santis, a younger and clearly vigorous filmmaker in 1949 when Bitter Rice (aka Riso amaro) was released, saw fit to infuse the film with a healthy dose of pulpy crime. Specifically, American pulpy crime; lurid, dangerous, kind of sexy. This infusion would be both Bitter Rice‘s calling card and the target of its naysayers.

The combination of an illicit couple’s jewel heist escape and depictions of the needy lives of the Italian common folk – here, mostly women from all professions who go to work in the Po Valley rice fields for 40 days each year – may sound like a precarious mash-up. On the contrary, it is managed expertly.

From the show stopping extended opening sequence, in which our criminals, stolen necklace in hand, attempt to evade the police at their heels by blending into the throng of departing female workers at the train station, it’s obvious we’re in the hands of an energized visual storyteller, one with empathy to spare. Bitter Rice is both a beautiful and respectable black and white neorealist portrait, and a fully functional crackling, sexy crime drama. As it takes its plot to the watery fields themselves for the duration of the story, it becomes apparent that Bitter Rice is at once “a film” and “a movie”.

As Pasquale Iannone’s essay that is included the new Criterion blu-ray details, Bitter Rice was not the first Italian film to attempt such a juxtaposition. Although the neorealist movement, with its painfully raw humanity and insistence on contemporary realism, was considered appropriately vital by many Italians per the country’s need to shed its past alignment with fascism, several filmmakers understood that its power and purpose could be more focused, even intensified, if wrapped up in cinema convention.

In classic Italian crime cinema and beyond, the men are often blunt, the women are often voluptuous, even impossibly beautiful, and their relationships tend to be terse. The main characters and couplings of Bitter Rice are no exception, although per its 1949 vintage, none of it is stale, or even non-organic. It is the core triumph of the film.

The collision of sensibilities is far from a wreck in the hands of De Santis, a director who made tightly timed, intensely framed and choreographed sequences play purely and naturally. In a series of lengthy, fluid dolly shots and geographic precision, Bitter Rice introduces itself thusly:

Ext. Train Station – Day: Dust is swirling in the air as scores of women bustle to the trains. Soon they will be leaving for the rice patties, off to take on difficult temporary harvesting work that we’ve been told (in a clever fourth wall-breaking direct address that turns out to be a live radio address) only women can do. The thieves (Doris Dowling and Vittorio Gassman), loot in hand and closely pursued, attempt to blend into the crowd of this very real annual pilgrimage.

The shear vastness and movement of the flowing masses would scream “epic!” in the hands of other directors, but De Santis, clearly moved by the reality of the women and taken with the idea of a sexy crime story, keeps things decidedly intimate. At no point is the convergence of neorealism and cinema glamour made more overt than the prolonged single shot that moves along the open windows of a train, witnessing mundane life in all its tired normalcy – an old man shaving, a couple bickering, et cetra. Fascinating. Suddenly, the camera is magnetized away from the train by the jazzy music pouring from an unseen record player, we are introduced to the entrancing Silvana (Silvana Mangano). More fascinating! She is dancing, shimmying for fun to the rowdy delight of all around. She soon says that they dance in her village every night. And, we believe her.

What to say about Mangano, anyhow…? Despite strong cases being made for other notable elements, the young actress completely owns this movie. It was her starring debut, even though it was initially supposed to be Gassman and Dowling’s show. But, as De Santis and his producer, one Dino de Laurentiis (who would go on to marry her), quickly realized, the camera just loves Mangano too much. The film was reworked to play upon her obvious virtues, internal and exterior alike.

Mangano.

Although Criterion’s blu-ray of Bitter Rice is one of their less expensive offerings ($30 MSRP as opposed to the usual $40), the company’s trademark care and effort is no less apparent. De Santis’ black and white compositions appear vibrant, deep, and fresh. Likewise, the film, presented in Italian with new English subtitles, sounds great as well.

There’s not as much in the way of extras as one might expect, considering Criterion’s often exaggerated reputation for having a lot of them. But, there are a few morsels provided here that help contextualize both the director and this film. Primarily, there is an hour-long Italian TV documentary about De Santis’ career and filmography. There is also a brief 2002 interview with the film’s writer, Carlo Lizzani, and a vintage trailer.

Thanks to its improved filmic clarity, we viewers are there, amid the backbreaking sun baked labor of the rice fields; we are there alongside of the bedazzled onlookers as Silvana dances her seductive boogie woogie. We are there in the gruesome meat processing room, as the stolen necklace plot plays out with moments that telegraph The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Perhaps most immediately striking is Criterion’s new, exquisitely pitch perfect cover art, painted by Ken Laager. To match, there is a small painted folded poster inside, housing the requisite essay on its opposite side. The sheer beauty of the image of Silvana lazing in the barracks with her treasured phonograph, brush strokes and paint globs ever present, makes the impractical aspect of reading the essay in unfolded roadmap fashion worthwhile.

Bitter Rice, as curated by Criterion, speaks to the strengths of what the company does, and how it does it. Here we have an increasingly obscure career highlight of an important filmmaker, rescued and made available in classy, informative, and entertaining fashion. Not forsaking its politics for its effective dime novel plot, or vice verse, Giuseppe De Santis’ Bitter Rice is something of a masterpiece. There’s something for almost everyone, and it’s a delight to discover.

The images included in this review are not necessarily an accurate representation of the blu-ray, and are intended purely as representation of the film itself. This review was originated for ScreenAnarchy.com, on Janary 12, 2016.