Our Look At The 1932 Best Oscar Winner And Other Matters Costume Drama-ry

DIRECTOR: FRANK LLOYD/1933

The winner for “Outstanding Production” of the 1932/1933 Oscar season (the category went through various iterations before arriving at the term “Best Picture” in 1962) is a film that many may be unfamiliar with today, but whose considerable appeal for contemporary audiences lay in a startlingly new way of portraying recent history. The film in question: Fox Films’ lavish 1932/33 production of Cavalcade.

The winner for “Outstanding Production” of the 1932/1933 Oscar season (the category went through various iterations before arriving at the term “Best Picture” in 1962) is a film that many may be unfamiliar with today, but whose considerable appeal for contemporary audiences lay in a startlingly new way of portraying recent history. The film in question: Fox Films’ lavish 1932/33 production of Cavalcade.

Based on the historical pageant play by Noël Coward, the film follows the rising and falling fortunes of a well-to-do British family as a microcosm of the first third of the Twentieth Century. Opening on New Year’s Eve 1899, the drama unfolds against three decades of political and social upheaval in Great Britain through the Second Boer War, the death of Queen Victoria, the sinking of the Titanic, the first World War, and on through the Roaring Twenties. The aristocratic Marryots – along with their erstwhile servants, the Bridges – are impacted by history in ways both personal and indirect; the “grand march of time” mixing domestic and celebrated events in a realistic and immediate fashion.

…

So why, you might be thinking at this point, have I never heard of this movie? Of the ten pictures nominated for the top award that “distribution season” – including such evergreens as the super-musical 42nd Street, a sublime Katharine Hepburn in Little Women, Frank Capra’s inner-city fairy-tale Lady for a Day, the inaugural social docudrama I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and a hip-swayin’ and innuendo-layin’ Mae West in She Done Him Wrong – Cavalcade has possibly been overshadowed by changing tastes in entertainment (particularly performance-style) and a premise that, well, instantly dated itself upon release.

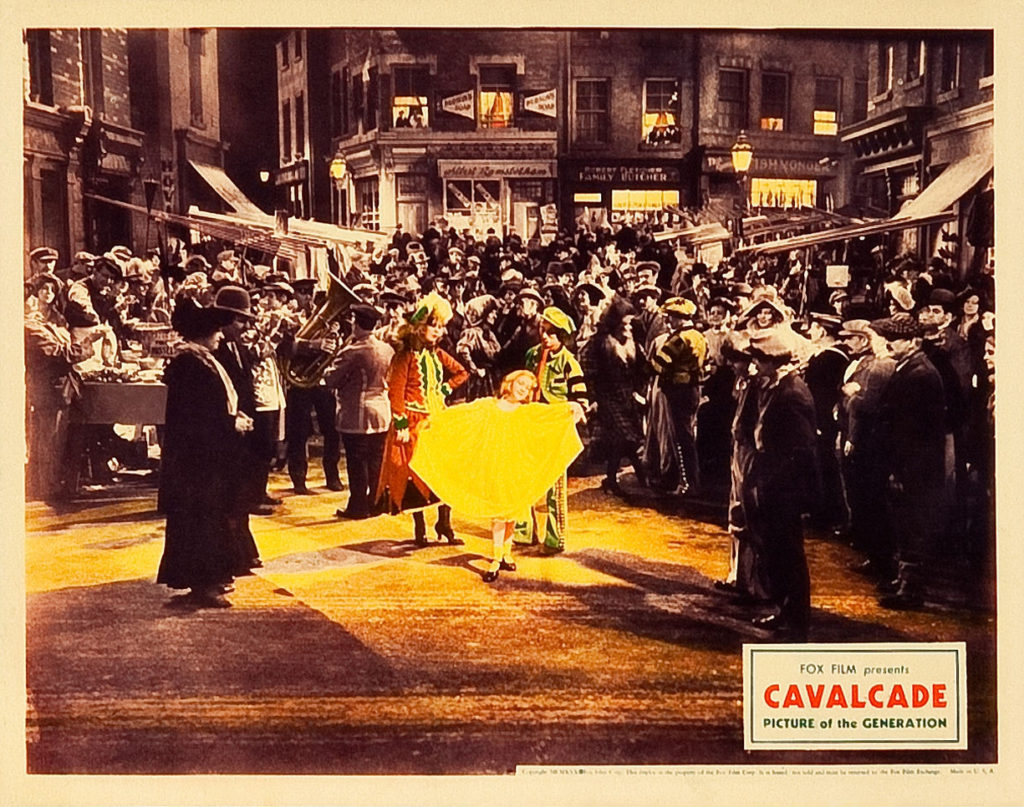

For audiences of the day, though, the recreation of, say, the massive warship leaving the London harbor for South Africa – carrying both the master, Robert Marryot (Clive Brook), and his servant, Alfred Bridges (Herbert Mundin) – was not only a set-piece of pure screen spectacle, employing hundreds of extras and a to-scale side-view of the ludicrously large boat, but also a vivid reminder of an event that was for many audience members still as real as living memory.

The self-proclaimed “picture of the generation” was just that: a screen-sensational attempt to make “history” its audiences had quite recently been through live and breathe anew, now imbued with the dramatic “significance” that became apparent only in retrospect.

According to the otherwise dry commentary accompanying the much-belated 2011 Blu-Ray release of Cavalcade, Noël Coward had apparently seen an old newspaper clipping of the “Relief of Mafeking” and it was this spectacular image of British soldiers departing for the Second Boer War which inspired a popular playwright known previously for light drawing-room comedies (Hay Fever, Private Lives, Design For Living) to try his hand at drama with a big “D”. Its original 1931 staging, with a “cast of hundreds” and hydraulic-revolving sets, was never repeated; so it is solely through this movie that Cavalcade and its legacy persists.

…

from left to right: Herbert Mundin as “Alfred Bridges”, Diana Wynward as “Jane Marryot”, Clive Brook as “Robert Marryot”, and Una OConnor as “Ellen Bridges”

Or is it? Overlooked among other Best Oscar winners, the film version of Cavalcade might, again, be entirely forgotten – consigned to the now-obscure fate of other then-“acclaimed productions” such as Broadway Melody (1929), Cimarron (1931), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), Gentleman’s Agreement(1947), etc. – if, in fact, its “grand idea” had not unaccountably provided shape and substance to many subsequent productions, particularly on British television.

Original 1971 cast of “Upstairs, Downstairs”

The wildly acclaimed 1971 – 1974 ITV series Upstairs, Downstairs, which singlehandedly popularized British costume drama on American television, stretched five seasons (or British “series”) out of the idea, emphasizing the “master/servant” dynamic from its very title. Once again focusing on two “families” – the wealthy and powerful Bellamys, sipping tea in their stately Belgravia townhouse, and their energetic and colorful servants a bustle of silver-polishing and meal-preparing activity below – Upstairs, Downstairs built upon the premise of real history and how it intruded upon, and even overturned, the notions of social class that had been at the heart of British life for centuries.

Third season cast of “Downton Abbey”

Even more recently, the even more ambitious ITV/PBS production of Downton Abbey (2010 – 2015; which will air its final episode on PBS March 6th) has been, from its very first scene, similarly impacted by Cavalcade‘s influence. Whereas Coward’s initial British historical drama used the watery North Atlantic grave of the Titanic as a major dramatic plot point, Downton Abbey turned the event into an instigating avalanche of Drama (again, with a big “D”) that, over the course of six seasons (or, again, British “series”), signaled the weakening influence of the British aristocracy on British social life. Through monstrous “entails”, servant intrigues, swooning romantic interludes, dramatic deathbed scenes, the destruction of war, changing social mores – well, the list goes on – the very apogee of Edwardian-to-Interwar British costumed history has once more paraded its highly-addictive influence (I personally call it “televisual crack”) on the hearts and minds of Anglophiles the world over.

In its various iterations, Cavalcade has proved much more venerable than its single (complete) staging and somewhat obscure (though award-winning) filming would suggest.

While I wouldn’t downplay the surface allure of, say, changing fashions represented by Ladies (and I hope the plural is permissible here) Marryot (Diana Wynyard), Bellamy (Rachel Gurney), and Grantham (Elizabeth McGovern) – particularly how corseted and bustled “ladies” went from looking like upholstered furniture in 1910 to the considerably freer and less restrictive draped gowns of the 1920s – I think the much deeper appeal of period drama lies in the mercurial character of “time” itself: illuminating the present through reflection on the past, Cavalcade and its heirs have invited a deeper popular appreciation of this inherently dramatic era of British social history.

Grim though the time period may seem – and there is a sense that something has been lost, or that “the light has gone out”, as Cavalcade‘s allegorically-linking “procession” moves forth – one can observe with each successive version of Britain’s cross-class, costumed fictional history lesson that, though change is often necessary, there is something of comforting value in nostalgically considering the past. (Plus, as an admitted male fan of costume dramas, I can attest that the changing fashions and décor certainly don’t hurt Cavalcade/Upstairs, Downstairs/Downton Abbey‘s fairy tale-like appeal.)

Finally, a few words on Cavalcade as a film. In viewing, if you can get past the occasional clunky line, the stiff-ish demeanor of some of the characters, and the inevitably stage-bound blocking style of the early sound period, I think you’ll come away quite affected; particularly if viewed with an audience, which is, of course, how these films are meant to be seen.

Still powerful are the overwhelming crowd scenes, the scenes at expansive-looking ports and railway stations, and, in particular, the terrifying (yet strangely beautiful) floating Germans Zeppelins, impressively recreating the first bombing attack on Central London during the first World War. Two key montage sequences, the first showing Britain embroiled in World War and the second clamorously ushering in a “society gone mad” through the late 20s into the 1930s, were devised by legendary production designer William Cameron Menzies (Things to Come [1936]) and are minor masterpieces of rapidly-edited phantasmagoria. “Spectacle!”, you’ll recall, was foremost on author Coward’s conception of the original play and Fox Films (soon to become Twentieth Century Fox) scored another spectacular production on a scale recalling the ever-ambitious studio’s previous Sunrise and 7th Heaven (both 1927).

Overall, even an hour and fifty minutes will whiz by as an audience fast-forwards through three crucial decades of British history. (And, if nothing else, may serve to inspire a Netflix/PBS-site perusal of the British costume dramas it inspired, which I personally think have actually gotten better with each successive “revision”.)

Based on a spectacular British play, lavishly adapted by an American studio, interpreted by (mainly) expatriate performers and (mainly) domestic technicians, contemporary winner of the highest honor an industry annually bestows upon itself – and then re-interpreted and re-adapted over the next 70 years for television audiences on both sides of the pond – Cavalcade is an “entertainment” in the grand-old sense of the word eminently worthy of re-discovery.