Hollywood’s He-Man And His Formidable Feet Of Clay

Our Film Admissions subject for the month of November is the athletic, adventurous, animated Burt Lancaster. Often referring to himself self-deprecatingly as “The Grin” (and affectionately parodied as such in Jean-Paul Belmondo’s memorable “impersonation” of the actor in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou [1965]), Lancaster was a star whose boisterous and robust popular image belied a deepening choice of roles, a considerable business savvy, and a persevering staying power throughout his 40+-year film career.

Our Film Admissions subject for the month of November is the athletic, adventurous, animated Burt Lancaster. Often referring to himself self-deprecatingly as “The Grin” (and affectionately parodied as such in Jean-Paul Belmondo’s memorable “impersonation” of the actor in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou [1965]), Lancaster was a star whose boisterous and robust popular image belied a deepening choice of roles, a considerable business savvy, and a persevering staying power throughout his 40+-year film career.

Always a true “performer”, Lancaster’s background in high school athletics, particularly an early interest in gymnastics, lead to his first career as an acrobatic circus and vaudeville entertainer. Partnered with lifelong friend (and later frequent co-star) Nick Cravat, as the first half of the flying trapeze act “Lang & Cravat”, the pair were quite successful performing in circuses and federally-funded “Theatre Project” venues during the Depression until a head-and-neck injury forced Lancaster to leave the profession in 1939. Following service in World War II, Lancaster turned seriously to acting on Broadway, eventually capturing the attention of Hollywood agent Harold Hecht who recommended the actor to producer Hal Wallis for the central role of haunted former prizefighter-turned-crook “’Swede’ Andersen” in his upcoming film of The Killers (1946), based on the short story by Ernest Hemingway. And so, at the age of 31, Lancaster made his film debut in a star-making performance, under the direction of master visualist Robert Siodmak, and opposite the impossibly-sexy Ava Gardner, in one of the key films noir of the 1940s.

With Ava Gardner in THE KILLERS (1946)

After numerous “tough guy” film noir roles — including performances in such classics as Jules Dassin’s grim prison drama Brute Force (1946), the bleak, fatalistic I Walk Alone (1948; his first of seven films co-starring Kirk Douglas), and, reuniting with director Siodmak, the superior, genre-defining Criss Cross (1949) — Lancaster unprecedentedly took control of his professional career as a Hollywood actor. Following his Academy Award-nominated performance in From Here to Eternity (1953), Lancaster embarked on a three-way partnership with Harold Hecht and writer James Hill to form “Hecht-Hill-Lancaster”, an independent production company that made some of the key films of the mid-to-late ’50s. The period saw the depth of Lancaster’s choice in roles increasing, including an anti-heroic role in Robert Aldrich’s Western Vera Cruz (1954) — another “H-H-L” production, in Carol Reed’s romantic circus melodrama Trapeze (1956), gave Lancaster the chance to show off his considerable acrobatic skills — all culminating in his frighteningly-assured performance as the odious, megalomaniac tabloid publisher “J.J. Hunsucker” in Sweet Smell of Success (1957).

ELMER GANTRY (1960)

As the title character of Elmer Gantry (1960), an opportunistic fire-and-brimstone evangelist, in director Richard Brooks’ adaptation of the Sinclair Lewis novel, Lancaster finally won the Academy Award for Best Actor, allowing a considerable range of choices to the always-adventurous actor. Highlights include his acclaimed turns as the Birdman of Alcatraz(1962), Richard Stroud, in John Frankenheimer’s biopic, a faded Sicilian aristocrat in Luchino Visconti’s historical epic The Leopard (1963), a treacherous U.S. General in the political thriller Seven Days in May (1964), and, entering his 5th decade, continuing his action roles in such intelligent (and increasingly socially and politically critical) thrillers as The Train (1964), The Professionals (1966), and Ulzana’s Raid (1972).

Beginning with his “comeback” performance as aging gangster “Lou Pascal” in director Louis Malle’s character-driven piece Atlantic City (1980), Lancaster settled comfortably into character roles for the remainder of his career, and is probably best remembered by modern audiences for his role as “Dr. Archibald ‘Moonlight’ Graham” in Field of Dreams (1989). However, in conclusion, this fan would like to point out two oft-overlooked performances in Lancaster’s vast filmography which equally showcase his unique qualities as an actor: first, as tragically-optimistic suburban he-man “Ned Merrill” in 1968’s The Swimmer and second, as manically-eccentric oil executive “Felix Happer” in 1983’s Local Hero. Skirting some narrow edge between magical charisma and dark dementia in both roles, separated by a distance of 15 years, Lancaster’s still-chiseled physical appearance in the former performance (at the age of 52) and still-overconfident swagger in the latter (at the age of 67) again belies an indelible depth of character and a flawed, all-too-human quality projected beneath the always-impressive surface. Join us, then, as some of our contributor’s record their first-viewing reactions to a whole slew of Burt Lancaster performances below!

Sweet Smell of Success

(1957, Hill-Hecht-Lancaster Productions, Dir. Alexander Mackendrick)

by Sharon Autenrieth

I could go write at length about what makes The Sweet Smell of Success a great film, but for this column I’ll hone in on Burt Lancaster’s performance as bitter, twisted, megalomaniac J.J. Hunsecker. He is a man with the power to build up or destroy, and he does both through his Broadway gossip column. That’s right: this is a movie in which the villain – and he is well and truly a villain – is a newspaperman. This evokes a time when a career could be destroyed through a sexual scandal, a marijuana bust, or rumors of Communist affiliations. It takes far more to alienate us from celebrities now, and perhaps that’s why there is no journalist today who elicits the fear kind of fear and obeisance that Hunsecker does in this movie. There once was, though. The character of J.J. Hunsecker was loosely based on Walter Winchell, a newspaperman and radio gossip commentator who reigned from the 1930s to the ’50s. The Sweet Smell of Success was a poison dart aimed right at Winchell, and he was thrilled when it did poorly at the box office. It wouldn’t be long before he’d see his career decline, though, having unwisely hitched his wagon to Senator Joe McCarthy and his Communist witch hunt. When McCarthy went down, his high-profile celebrity supporters went with him.

I could go write at length about what makes The Sweet Smell of Success a great film, but for this column I’ll hone in on Burt Lancaster’s performance as bitter, twisted, megalomaniac J.J. Hunsecker. He is a man with the power to build up or destroy, and he does both through his Broadway gossip column. That’s right: this is a movie in which the villain – and he is well and truly a villain – is a newspaperman. This evokes a time when a career could be destroyed through a sexual scandal, a marijuana bust, or rumors of Communist affiliations. It takes far more to alienate us from celebrities now, and perhaps that’s why there is no journalist today who elicits the fear kind of fear and obeisance that Hunsecker does in this movie. There once was, though. The character of J.J. Hunsecker was loosely based on Walter Winchell, a newspaperman and radio gossip commentator who reigned from the 1930s to the ’50s. The Sweet Smell of Success was a poison dart aimed right at Winchell, and he was thrilled when it did poorly at the box office. It wouldn’t be long before he’d see his career decline, though, having unwisely hitched his wagon to Senator Joe McCarthy and his Communist witch hunt. When McCarthy went down, his high-profile celebrity supporters went with him.

But back to Hunsecker. Lancaster plays him with the obsessiveness and pride of Othello, and the cruelty and cunning of Iago. When he arranges for a smear campaign against a young musician (Martin Milner) it seems as deadly as a murder for hire. Watching him browbeat Milner’s character into an argument is like watching the proverbial cat toying with a mouse. And when he shames a politician looking for a favor, Lancaster’s every word drips with contempt. Hunsecker’s ego is matched only by his disdain for everyone around him – except for his sister Susan. And poor Susan! To be the love object of a man who is, in fact, incapable of love is a bitter lot indeed.

As I said, there’s much to recommend The Sweet Smell of Success: the smart, spiky script by Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman; the jazz score by Elmer Bernstein; the brilliant cinematography by James Wong Howe; and the central performance by Tony Curtis as a slimy, press agent – Hunsecker’s “trained poodle”. But not least is Lancaster’s truly ugly villain. I won’t soon forget him.

Rocket Gibraltar

(1988, Columbia Pictures, dir. Daniel Petrie)

by Justin Mory

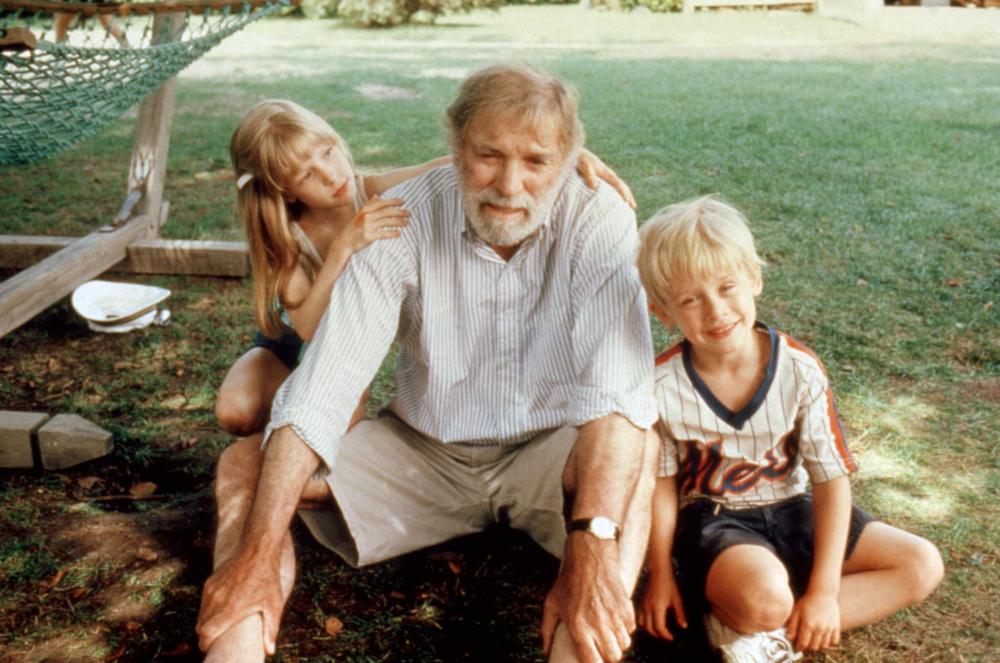

ROCKET GIBRALTAR, Angela Goethals, Burt Lancaster, Macaulay Culkin, 1988

© Colombia Pictures/

Growing up, there were two larger-than-life figures that loomed heavily over my childhood: my uncle and my grandfather. My mother’s older brother edited and published an internationally-known film periodical during the ’70s and later co-founded one of the largest domestic distributors of comic books and pop cultural ephemera during the ’80s to mid-’90s. It’s from him, I think, that I get my obsession with 20th century pop culture; especially the movies. As a teen, my father’s father apprenticed with a former Ringling Bros. clown and acrobat at a circus school in Manitowoc, Wisconsin and, as an adult, became a university gymnastics coach; eventually, in his retirement, my grandfather started his own summer program for local kids in Baraboo, Wisconsin at its Circus World Museum. It’s due to him that I know how to juggle a bit, but, more lastingly, that I have an equally strong obsession with the history of show business and the lives of show business folk.

Growing up, there were two larger-than-life figures that loomed heavily over my childhood: my uncle and my grandfather. My mother’s older brother edited and published an internationally-known film periodical during the ’70s and later co-founded one of the largest domestic distributors of comic books and pop cultural ephemera during the ’80s to mid-’90s. It’s from him, I think, that I get my obsession with 20th century pop culture; especially the movies. As a teen, my father’s father apprenticed with a former Ringling Bros. clown and acrobat at a circus school in Manitowoc, Wisconsin and, as an adult, became a university gymnastics coach; eventually, in his retirement, my grandfather started his own summer program for local kids in Baraboo, Wisconsin at its Circus World Museum. It’s due to him that I know how to juggle a bit, but, more lastingly, that I have an equally strong obsession with the history of show business and the lives of show business folk.

Our Film Admissions subject for this month, Burt Lancaster, was born the same year as my grandfather, 1913, and shares a similar history as an acrobatic circus performer in his youth who later turned to another profession as an adult. The film I chose for this month, the late ’80s family comedy/drama Rocket Gibraltar, comes off as a sort of career summation for Lancaster and, in the role of elderly writer/producer/professor/comedian “Levi Rockwell,” reminded this viewer very much of what its like to be a young kid very much in awe of an accomplished older relative. As 7-year-old “Cy Blue Black,” played by Macaulay Culkin in his first movie, Levi’s youngest grandkid leads a band of siblings and cousins (with names like “Orson” and “Kane”) at a family gathering in devising a legacy befitting their legendary grandfather: a viking funeral in the titular-rebuilt skiff they mistake for its original name, “The Rock of Gibraltar.”

Watching a slew of other movies in connection with Rocket Gibraltar earlier this month — including the previously unseen Lancaster movies Vengeance Valley (1952), The Kentuckian (1955), The Hallelujah Trail (1965), and Go Tell the Spartans (1978) — I was struck by what a magical figure Lancaster developed into as he aged so gracefully on-screen. Like an older relative one can’t help but idolize, one spends a lifetime trying to live up to the example they set and the legacy they leave.

Atlantic City

(1980, Cine-Neighbor, dir. Louis Malle)

by Robert Hornak

Feels like a 70s movie tilting mournfully toward the edge of the 80s. An Altman title over a Lumet-like, city-centric fable of lost 70s characters watching as their boardwalk neighborhood, as surely as their decade, is demolished with a wrecking ball to make way for bigger, flashier temples of cash. I was prepped by Netflix to expect a straight-up mob drama-slash-romance, but found instead an unassuming little gem of quiet comedy all mixed up with Louis Malle’s warmly detached observations, like de Tocqueville with lens choice, on just where we were in America at the turn of the decade: the crumbling facades seem almost comforting to the gaggle of self-deluded, self-defeating wanderers. By the time Lancaster, walking along the boardwalk, says wistfully to a new friend, “You should have seen the Atlantic Ocean back then,” I knew I wasn’t watching real people, but ghostish icons of brokenness and resigned longing, perhaps waiting for someone to tear them down and build them back up, but better this time.

Feels like a 70s movie tilting mournfully toward the edge of the 80s. An Altman title over a Lumet-like, city-centric fable of lost 70s characters watching as their boardwalk neighborhood, as surely as their decade, is demolished with a wrecking ball to make way for bigger, flashier temples of cash. I was prepped by Netflix to expect a straight-up mob drama-slash-romance, but found instead an unassuming little gem of quiet comedy all mixed up with Louis Malle’s warmly detached observations, like de Tocqueville with lens choice, on just where we were in America at the turn of the decade: the crumbling facades seem almost comforting to the gaggle of self-deluded, self-defeating wanderers. By the time Lancaster, walking along the boardwalk, says wistfully to a new friend, “You should have seen the Atlantic Ocean back then,” I knew I wasn’t watching real people, but ghostish icons of brokenness and resigned longing, perhaps waiting for someone to tear them down and build them back up, but better this time.

Over maybe a dozen Lancaster movies in the last clutch of months, I’ve become fascinated (read: man-crushed) by his unforced combo of staccato-tongued, rock-toothed virility and near-dainty sensitivity, mainly in his hands – the way he holds things, works with things, floats them through the air while describing things – and the whole action, violent or loving, bracketed by his mammoth, 40s-robot shoulders. Sometimes when his face is in closeup, you feel like his jaw could wreck your TV screen. Over his career he filled up that monolith frame with mostly what was worthy of it – in Brute Force, it’s loyalty, determination, in Elmer Gantry, it’s the thick piety of the pseudo-sacred and the full gusto of the profane, in The Leopard, it’s the forsaken memories of an entire nation. So I was surprised to find in Atlantic City a Lancaster made small. He’s so shrunken by self-directed lies (that he was a mob big shot in the old days when he was at best a gofer), so needful of regard that a lie told to him by a swindler (“A guy in Vegas says you’re the man to see”) is absorbed as truth like a man dying of thirst, and so against his heroic type that when gal-pal Susan Sarandon is attacked by a couple of Philadelphia toughs, he coils that big bull frame into a shamed and wincing bystander. The whole movie is a fuzzy-centered affront to the entirety of one actor’s image. But it’s for a good cause, and he’s brilliant even when shrunken – his old Hollywood image is what makes this character all the richer as he stands crumbled amidst the crumbling city, like Ozymandias in a fedora. I love this movie.

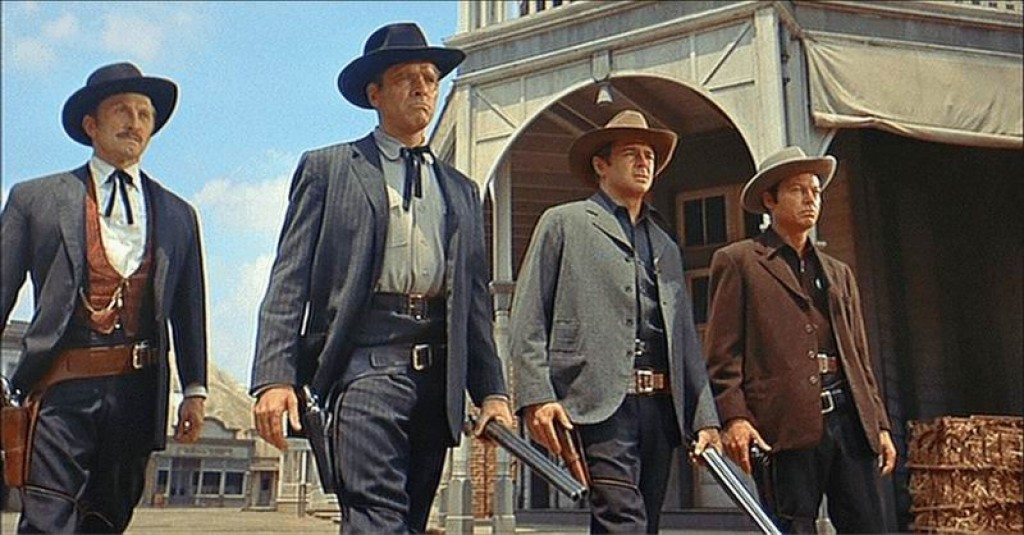

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

(1957, Paramount Pictures, dir. John Sturges)

by Jim Tudor

The Dark Knight. Casino Royale. Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

The Dark Knight. Casino Royale. Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

If every other film version of the historic 1881 30-second shootout near (not actually at) the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona that I’ve seen is remembered as a bit more action-tropey, a bit more “adapted for the screen”, then this 1957 Western retelling is the “dark and serious” version. Not that I’ve seen every film made about Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday and their showdown with the Clantons and their outlaw comrades. I haven’t. But when I think about the “biggies” of this oft-told tale (nearly every decade since the 1930s has at least one to claim), those being 1946’s My Darling Clementineand 1993’s Tombstone, their dark natures aren’t the first things that come to mind. With the former, it’s Henry Fonda’s Earp balancing on that chair on his porch. With the latter, it’s Val Kilmer’s scene-stealing turn as an ailling Holliday. For the record, I still give the edge to John Ford’s Clementine.

Nevertheless, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, directed by testosterone-fueled filmmaker John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven), has much in its favor. The second of seven screen collaborations between Burt Lancaster (a looming, stoney Earp with soulful eyes) and Kirk Douglas (another scene-stealing Holliday who’s good, but not nice), Gunfight proved so popular with the masses that the actual event came to be known by the same name. It’s a two-hour dramatic chronicle with occasional gunplay, not terribly concerned with telling the facts (here, the title event runs over five minutes), although Lancaster is said to have done extensive research to properly play the part. (Just don’t looks for Earp’s large mustache.)

Gunfight is a fine film with a satisfying weight about it, yet not a lot of fat. There is shocking violence: When characters get shot, they writh in pain, and bleed bright red blood. It’s an above-average execution of a post-High Noon adult-centric Western, even as, typically of American 1950s films, characters sack out from a long day of riding beautifully photographed natural landscapes around a phony studio-based campfire. But Sturges, sometimes criticized for lack of style, peppers his outdoor settings with subtly odd trees that droop, swoop, and criss-cross in abnormal ways. Whether this detail is intended metaphorically or not, it’s there, and lends a lingering oddity to the otherwise work-a-day Western town locations. The Lancaster/Douglas chemistry, however, is already in place, making for an interesting Earp/Holliday dynamic – two flawed, complex characters that never quite see eye to eye, but long to amount to something.

From Here to Eternity

(1953, Columbia Pictures, dir. Fred Zinnemann)

by Krystal Lyon

Why is that beach scene so classic? It lasts about a half a second and it looks totes uncomfortable! And who looks like Deborah Kerr when they get out of the ocean? I know I don’t. And why is every upper level officer in the army depicted as a total nincompoop? They are only interested in boxing or other men’s wives, or beating people to death. And who tries to sneak back into the army barracks at Pearl Harbor on December 7th? You know you’re gonna get shot! From Here to Eternity is a total melodrama that is over the top and a great example of the Golden Age of Cinema. And even with all that drama and all those unreasonable circumstances it was nominated for 13 Oscars and won 8! So what makes it so important? Is it Frank Sinatra’s Oscar winning good-guy role? Maybe it’s Donna Reed dropping truth bombs like, “And I’ll be happy because when you’re proper you’re safe.” (Also an Oscar winning role.) Or possibly It’s Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt, Montgomery Clift, playing Taps after his friend dies. All of those are roles were great, but I think the reason From Here to Eternity is ranked in most Top 100 Lists is because of Burt Lancaster, Deborah Kerr and that forbidden love scene on the beach.

Why is that beach scene so classic? It lasts about a half a second and it looks totes uncomfortable! And who looks like Deborah Kerr when they get out of the ocean? I know I don’t. And why is every upper level officer in the army depicted as a total nincompoop? They are only interested in boxing or other men’s wives, or beating people to death. And who tries to sneak back into the army barracks at Pearl Harbor on December 7th? You know you’re gonna get shot! From Here to Eternity is a total melodrama that is over the top and a great example of the Golden Age of Cinema. And even with all that drama and all those unreasonable circumstances it was nominated for 13 Oscars and won 8! So what makes it so important? Is it Frank Sinatra’s Oscar winning good-guy role? Maybe it’s Donna Reed dropping truth bombs like, “And I’ll be happy because when you’re proper you’re safe.” (Also an Oscar winning role.) Or possibly It’s Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt, Montgomery Clift, playing Taps after his friend dies. All of those are roles were great, but I think the reason From Here to Eternity is ranked in most Top 100 Lists is because of Burt Lancaster, Deborah Kerr and that forbidden love scene on the beach.

Burt is our boy for the month and while I think he was good as sergeant Milt Warden I don’t think he shines as brightly as Clift, Reed or Sinatra. (Although he was nominated for an Oscar.) But old Burt contributed to “the most romantic scene in cinema”. He came up with the idea of lying on the beach, in the surf while kissing Karen Holmes, Kerr. So, you have climatic music, waves crashing, a man and woman rolling around, a lot of skin. It’s basically an adulterous sex scene. Not your average fare for 1950’s depiction of army life. It was radical! And here’s the kicker, he’s such a good guy and her husband’s such a jerk that you are actually rooting for this affair. That scene and that relationship made love complicated, but that wasn’t new to cinema. Film Noir made love complicated, heck Charlie Chaplin made love complicated. But that scene is epochal, it’s recognized, it’s mimicked and repeated because it’s a powerful image of passion. It’s something most everyone wants, passion. I want it, but not necessarily with a wave flushing sand up my swimsuit. And that folks, is my real film admission!