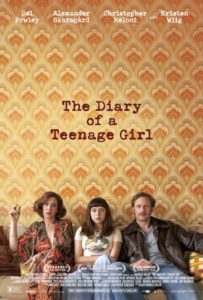

Bel Powley Delivers as a Girl at the Confusing Intersection of Love, Lust, and Longing

DIRECTOR: MARIELLE HELLER/2015

Note: Let me be honest with you up front. I am not going to recommend that you see The Diary of a Teenage Girl. I am also not not going to recommend The Diary of a Teenage Girl. The movie earns its R-rating, and then some, with strong sexual content, graphic nudity, drug use, and lots and lots of swearing. Consider yourself warned.

Note: Let me be honest with you up front. I am not going to recommend that you see The Diary of a Teenage Girl. I am also not not going to recommend The Diary of a Teenage Girl. The movie earns its R-rating, and then some, with strong sexual content, graphic nudity, drug use, and lots and lots of swearing. Consider yourself warned.

Phoebe Gloeckner was a teenager when she had her first sexual relationship – with her mother’s boyfriend. She transformed this memory and many others from her adolescence into her graphic novel The Diary of a Teenage Girl, now adapted for the screen by writer/director Marielle Heller. This is Heller’s first feature film in either of those roles. If you see The Diary of a Teenage Girl, let that sink in. This is an amazing piece of work for a first film: funny, distressing, lyrical, grim, and with terrific insight into human behavior. Heller championed this film into existence; first adapting it for the stage and even starring as the central character during the play’s 2010 run. Now that Heller has brought it to the screen, her zeal for Minnie Goetz (the teenage girl of the title) has been fully realized in a performance by English actress, Bel Powley.

Powley’s Minnie is 15, living in mid-70s San Francisco. She lives with her mother, Charlotte (Kristen Wiig) and younger sister, Gretel (Abby Wait); but in most meaningful ways, Minnie is on her own. Charlotte is a single mother wearing feminism and radical politics like this season’s fashions, and parenting by not-so-benign neglect. Gretel is a quiet, worried observer; but her attentions are not welcomed by Minnie. There is no one providing moral guidance for Minnie, no one paying much attention to whether she passes her classes at school, no one who seems particularly concerned with where she goes or who she is with. Powley, who is 23, plays a young teen with complete authenticity. With her large eyes, full mouth and heavy bangs, she slips easily between childishness and a sexual force with which to be reckoned – and therein lies the hazard for Minnie. Movies often give us clichés about “sexual awakening”. At 15, Minnie is already wide awake and hungry for experience. But she is also still a child, still insecure about her own desirability, still making the oft-repeated mistake of believing that “Someone wants to have sex with me!” is synonymous with “Someone loves me!”

Powley’s Minnie is 15, living in mid-70s San Francisco. She lives with her mother, Charlotte (Kristen Wiig) and younger sister, Gretel (Abby Wait); but in most meaningful ways, Minnie is on her own. Charlotte is a single mother wearing feminism and radical politics like this season’s fashions, and parenting by not-so-benign neglect. Gretel is a quiet, worried observer; but her attentions are not welcomed by Minnie. There is no one providing moral guidance for Minnie, no one paying much attention to whether she passes her classes at school, no one who seems particularly concerned with where she goes or who she is with. Powley, who is 23, plays a young teen with complete authenticity. With her large eyes, full mouth and heavy bangs, she slips easily between childishness and a sexual force with which to be reckoned – and therein lies the hazard for Minnie. Movies often give us clichés about “sexual awakening”. At 15, Minnie is already wide awake and hungry for experience. But she is also still a child, still insecure about her own desirability, still making the oft-repeated mistake of believing that “Someone wants to have sex with me!” is synonymous with “Someone loves me!”

The one who wants to have sex with Minnie is her mother’s boyfriend, Monroe (Alexander Skarsgard). He’s in his mid-30s, handsome enough, and less than fully adult himself. He’s into EST and dreams of building a vitamin empire. Many of his public encounters with Minnie take the form of horseplay and teasing, as if they are siblings. But there’s much, much more going on – and that’s what initially makes The Diary of a Teenage Girl so difficult to watch. This is San Francisco at the tail end of the hippie era: it’s was undoubtedly a more liberal climate than the one in which I grew up, just a few years later, in central Missouri. But it is not okay for a 35 year old man to carry on a secret affair with a 15 year old. Not now, not then. Minnie is the initiator in the sexual relationship (a change from the novel, and one that bothers and puzzles me), but Monroe is more than willing to do what Minnie asks. The relationship goes on for some time, even as Monroe keeps talking about ending it. The power between these two seems to shift back and forth. “You have some kind of hold on me,” Monroe tells Minnie at one point. But the movie’s repeated references to the kidnapping of Patty Hearst left me wondering if there was a bit of Stockholm Syndrome for Minnie, too. She wonders if she is attractive enough to ever have anyone else want her, and that kind of self-doubt is a powerful tether. At one point Monroe scolds Minnie for not being discreet enough in hiding her feelings for him. “I have feelings, too,” he says, “but I know how to restrain myself.” It’s a richly ironic line considering the circumstances.

Minnie’s sexual experiences are not limited to her relationship with Monroe. She gains the attention of a boy at school, but he is alarmed by how “intense” she is physically. “Having sex with you scares me,” he confides. This is a deal breaker for Minnie. If she cannot express the full force of her sexuality with this boy, why bother with him at all? Minnie, who often expresses herself through cartooning, follows this scene by drawing a cartoon of herself as a giant, lustful monster, casting this unworthy boy aside.

Minnie’s sexual experiences are not limited to her relationship with Monroe. She gains the attention of a boy at school, but he is alarmed by how “intense” she is physically. “Having sex with you scares me,” he confides. This is a deal breaker for Minnie. If she cannot express the full force of her sexuality with this boy, why bother with him at all? Minnie, who often expresses herself through cartooning, follows this scene by drawing a cartoon of herself as a giant, lustful monster, casting this unworthy boy aside.

Sometimes Minnie seems afraid of and alarmed by her desires. “I get distracted sometimes,” she confides to her imaginary friend and real life role model, cartoonist Aline Kominsky. “Overwhelmed by my all consuming thoughts about sex and men….I just want to be touched, I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” At other times, Minnie embraces her sexual appetite with a fervor that is…well, frankly, dangerous. If she really is too “intense” for normal people, then she’ll accept this identity and become the lustful monster her young boyfriend sees her as. And so Minnie continues not only in her relationship with Monroe, but tries out other sexually reckless behavior. She and her best friend Kimmie (Madeleine Waters) even “play” at prostitution one night, although they both feel creeped out by it the next day and make a pact not to repeat that particular behavior.

I want to pause here to point out something that I think The Diary of a Teenage Girl does very well, and which feels almost unprecedented. It takes seriously the sexuality of a teenage girl. A film festival about horny teenage boys could last for months, and girls have certainly been objects of desire in those movies. But Minnie is her own agent, with her own very powerful drives and longings. This remains a counter-cultural message, the notion that girls have sexual appetites of their own. Back in central Missouri, when I was a teenage girl, I was being told that boys wanted sex, but girls just wanted love and commitment. What did that mean for a girl – or millions of girls – who could feel in their very beings that this wasn’t the whole story? Was there something wrong with us?

When Minnie expresses her confusion over her desire to be touched, Aline responds, “Maybe you’re a nympho,” then makes clear she’s only kidding. “Nah….we all want to be touched.”

Of course, as the movie also makes clear, Minnie’s hunger for touch may go deeper than just a healthy sexual appetite. She tells us, in the voice over narration that structures the movie, that her mother rarely touches her, but it hasn’t always been that way. When she was a little girl Minnie received plenty of motherly affection – until her controlling step-father suggested to Charlotte that there was something “unnatural” and “sexual” in Minnie’s need for affection from her. And so Charlotte turned off her physical affection like shutting off a faucet, and now Minnie finds herself still hungry for touch and getting it nearly anywhere she can. She may not see the connections, but Phoebe Gloeckner and Marielle Heller certainly do, and so can we in the audience, as we watch the film.

Of course, as the movie also makes clear, Minnie’s hunger for touch may go deeper than just a healthy sexual appetite. She tells us, in the voice over narration that structures the movie, that her mother rarely touches her, but it hasn’t always been that way. When she was a little girl Minnie received plenty of motherly affection – until her controlling step-father suggested to Charlotte that there was something “unnatural” and “sexual” in Minnie’s need for affection from her. And so Charlotte turned off her physical affection like shutting off a faucet, and now Minnie finds herself still hungry for touch and getting it nearly anywhere she can. She may not see the connections, but Phoebe Gloeckner and Marielle Heller certainly do, and so can we in the audience, as we watch the film.

I’ve omitted much mention of Minnie’s art. She is a gifted cartoonist, and is constantly doodling her experiences and fantasies. Many of these cartoons are animated in The Diary of a Teenage Girl, woven playfully into the live action scenes. They are charming and funny, and sometimes filthy (the influence of R. Crumb is strong): when Monroe sees Minnie’s sketchbook he tells her not to show it to anyone; some of it’s “kind of weird”. Here, too, Minnie’s real thoughts and feelings seem scary and unacceptable to those around her. But her art will provide a renewed sense of purpose when she needs it most, and if that seems a bit hokey and cliché we must acknowledge that this was Phoebe Gloeckner’s story, and she’s built a very successful career as an artist after her rocky adolescence.

But about that rocky adolescence…it’s what makes The Diary of a Teenage Girl so very uncomfortable to watch. It’s raw in its depiction of Minnie’s life, and I had to remind myself more than once that Bel Powley is not a minor, but a 23 year old actress. Even so, this movie is not for everyone. The promo material emphasizes that the movie tells Minnie’s story “without judgment.” I was a bit worried about that, given the central plot point. I didn’t want a soft focus adult/child love affair a la The Summer of ’42. I’m not sure I want statutory rape to be depicted “without judgment”. But no imposed judgment needs to be applied to the characters in this movie. Their failings are carefully observed, the trajectory of Minnie’s life is clear: this is not a romanticized view of a sexual relationship between an adult and a minor. Monroe is both manipulative and emotionally stunted. Minnie’s choices, which she tries to see as bold, adventurous and empowered, lead her into some dark and disorienting places. She prevails, yes, but that outcome is by no means guaranteed. With no one else to provide guidance, Minnie finally recognizes her own internal boundary, the line she does not want to cross, and she pulls out of the downward spiral. She’s a girl with a ferocious hunger for life and experience, and she finally uses that internal strength to say “No”.

There is no sexual shaming in The Diary of a Teenage Girl. Minnie’s sexuality is not treated as a problem, although coming to express it in safe and healthy ways is a learning process for her. The movie is not afraid of holding uncomfortable ideas in tension, even acknowledging that genuine sexual pleasure can exist in a relationship that is emotionally damaging. Minnie enjoys being with Monroe, but he is not good for her. Eventually, she comes to understand this for herself.

There is no sexual shaming in The Diary of a Teenage Girl. Minnie’s sexuality is not treated as a problem, although coming to express it in safe and healthy ways is a learning process for her. The movie is not afraid of holding uncomfortable ideas in tension, even acknowledging that genuine sexual pleasure can exist in a relationship that is emotionally damaging. Minnie enjoys being with Monroe, but he is not good for her. Eventually, she comes to understand this for herself.

Minnie’s final speech in The Diary of a Teenage Girl is a bit disappointing. Having extricated herself from more than one exploitative relationship, Minnie now declares that, unlike her mother, she doesn’t need a man. In fact, she doesn’t need anyone. If no one ever loves her, she’ll be fine on her own. Although it’s delivered as unironic empowerment, it feels both trite and untrue. Personal integrity doesn’t mean giving up on meaningful relationships. We were not created to be alone and unloved. The good news is that the credit sequence at the film’s end beautifully and unexpectedly subverts that speech. Perhaps Minnie hasn’t been quite as alone as she’s seemed, after all.