At 25, Spike Lee’s Controversial Classic Is As Relevant As Ever

DIRECTOR: SPIKE LEE/1989

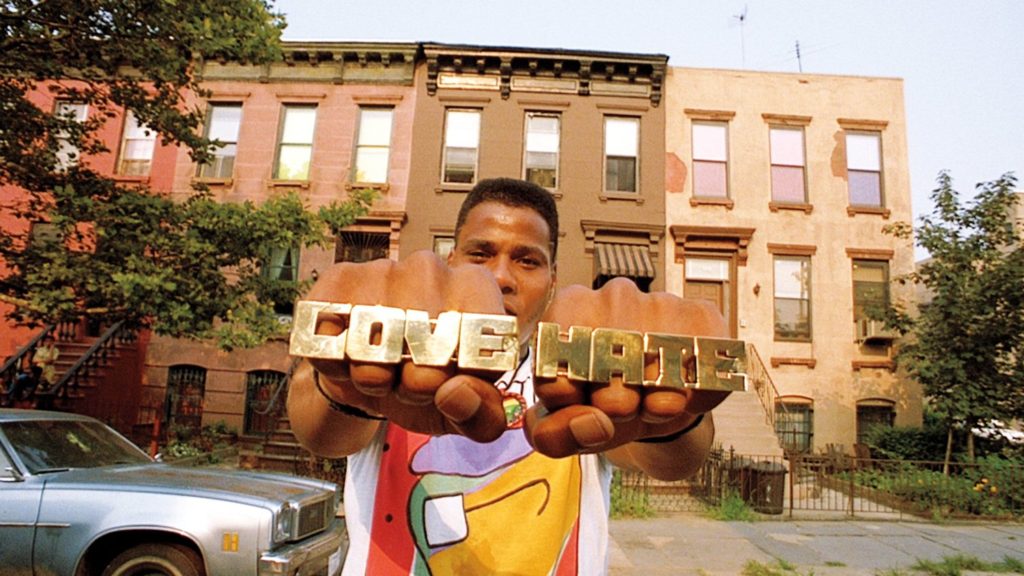

Twenty-five years ago, Spike Lee was a new face (just look at him as Mookie – a kid!!) looking to fight the power. His third film, Do the Right Thing, did just that. An incendiary firebrand, it hit on some of the most uncomfortable aspects of race relations in America, then or now.

As others will point out, recent news out of Ferguson, Missouri render the previous sentence far less cliché than it ordinarily would read. But Spike Lee’s film went beyond the prophetic, challenging all filmgoing audiences to rethink the all-too-reductive term “black community”. Do the Right Thing is a tight, vibrant, spunky, fun film in addition to being a rightfully challenging one. There is no “plot” in this chronicle of a hot, hot day in the life of an urban city block. Boldly, humanly, the African-American characters are all distinct, debating, engaging, and opinionizing about all sorts of things. This is the greatest unsung triumph of DtRT: That black community is rich, diverse, and intensely multi-facetted.

Several ZekeFilm contributors have shared their own experiences as to how the film affected them. The fact that we tend to share a certain white middle class shock should do nothing to lessen the validity of our observations, or the power of this film:

Sharon Autenrieth

ZekeFilm contibuting writer and board member

I saw Do the Right Thing shortly after it was released and watched it again this week. What strikes me, on rewatching, is that I was right to be floored by the movie 25 years ago. It is a masterful piece of filmmaking and I’m frankly in awe of what Spike Lee accomplished.

The rap classic “Fight the Power” may be the most famous song featured in the film, but the movie itself feels like jazz. Characters play off of each other, the script comes across in blazing riffs, scenes are saturated with color and movement, and the energy never flags for a moment. As for Lee, he wrote the script, directed the film and played the unassuming everyman at it’s center, Mookie.

It’s stating the obvious to say that Do the Right Thing seems as relevant now as when it was made. Living in the St. Louis area, I have thought of this movie over and over in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s death. But here’s the thing about Do the Right Thing: as bold as the style of the film is, Lee used that style to accomplish something even bolder – he created empathy for every character. No one seems like a monster, no one seems like a saint.

The classic question raised by the film is whether the viewer is more upset about the death of Radio Raheem or the smashing of the window at Sal’s Pizzeria. To me this choice has always seemed inadequate. Watching the movie again I reacted as I reacted 25 years ago: I don’t want Radio Raheem to die. I don’t want Sal’s to be destroyed. I don’t want any of it to happen, and I lament with Mother Sister (Ruby Dee) as she wails in the street during the riot – even though she’d screamed “Burn it down!” only a few minutes before. What Do the Right Thing offers is the tension between conciliation and uprising, between respectability politics and rage, between “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and “Fight the Power”. In the face of persistent racism and injustice, what is the right thing to do? Lee doesn’t give us a clear answer, but he knows what’s at stake. He puts another, still pressing, question in the mouth of Samuel L. Jackson’s radio DJ Mister Senor Love Daddy: “Are we gonna live together? Together, are we gonna live?”

?????????????

Justin Mory

ZekeFilm contributor

I first watched Do The Right Thing for an assignment in a US History course in my junior year of high school. I had initially asked to report on Driving Miss Daisy, which had won the Academy Award in the year DTRT hadn’t received the Best Picture nomination, but the teacher, wisely in retrospect, suggested the Spike Lee movie (or “joint,” I should say) instead, which I had then never heard of. (I’m awfully glad he made that suggestion.)

As I recall from my first viewing, the credits sequence, with actress Rosie Perez frenetically dancing in front of stylized, urban settings to a Public Enemy theme, threw me off a bit, initially—making me expect something along the lines of the then-popular sketch comedy show In Living Color, which, from my white suburban background, had been my only exposure to that style of performance—but the heavily-saturated, richly-set tones of director of photography Ernest Dickerson’s cinematography grabbed me from scene 1. From a low angle view of street vendor “Smiley”, hawking photos of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X to indifferent passers-by, the establishing scenes perfectly evoked the sun-baked, vivid atmosphere of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn on the Hottest Day Of The Year for me.

Indeed, as I, in short order, was introduced to indelible characters such as Da Mayor, Mother Sister, Radio Raheem, Mookie, his sister Jade, pizzeria owner Sal & his boys, along with too many others to mention (this is just one of the great casts of any film and of any era, period), what really drew me in was the sense of COMMUNITY (bold, all-caps) director Lee and his collaborators created. Very few movies succeed in capturing a sense of time and place honestly and realistically, but Brooklyn, NY, Summer of 1989 is one of the great settings in movie history, with Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, the Korean grocers across the street, the dilapidated brownstone buildings, the lounging street corners, and the post-tenement interiors becoming like physical geography in the minds of its viewers.

So yes, when I first saw the movie, and was so enjoying the characters and atmosphere, I was taken aback, even shocked, when a character’s response to a horrifying act of brutality suddenly and irrevocably destroyed such a tightly-knit community! But that’s entirely the point. In the end, what’s a bit of property damage when compared to a human life?

Jim Tudor

ZekeFilm Co-Founder

A confession: I didn’t like Do the Right Thing. I first saw it on a lousy VHS rental copy several years after it came out. As a conservative suburban white college kid being inundated regularly with opposing opinion, I went into DtRT with my guard up. Knee jerky, I denounced the film in what proved to be a very lively email exchange with my progressive friend, Drew Newman. At the time, I thought I was being patient with Drew’s exasperated disbelief that I could dismiss the film as “wrongfully open-ended” or “too preachy”, or whatever the heck I was spouting at the time. But the truth is that Drew was being patient with me. Several years later, something twitched unexpectedly in my evolving film geek judgement, and I found myself purchasing the Criterion DVD of Do the Right Thing. When I let Drew know that, he couldn’t resist replying, “Our boy’s growing up!”

The film is a masterpiece, one of the best of the 1980s, and maybe ever. This may be the one film in which Spike Lee was hitting on ALL cylinders. And that’s the truth, Ruth.

Dave Henry

ZekeFilm Co-Founder

I don’t know what it feels like to be oppressed because of my skin colour. But I know what it feels like to be oppressed by a family that is supposed to love, nurture, and take care of me.

I don’t know what it feels like to be trapped in a ghetto. But I know what it feels like to be trapped in an abusive home from which I could not escape, no matter how desperately I wanted to.

I don’t know what it feels like to be choked by the police. But I know what it feels like to be beaten in a fit of rage by someone twice my size.

I don’t know what it feels like to have my body objectified because of its hue. But I know what it feels like to have control of my body taken away from me.

I don’t know what it feels like to belong to a people whose voice has been consistently silenced. But I know what it feels like to not be heard or taken seriously; to be seen as a joke or a nuisance. I know what it feels like to be stifled.

I don’t know what it feels like to belong to an economically oppressed subculture. But I know what it feels like to be desperately poor; to not know where my next meal or tank of gas is coming from; to live in constant fear of eviction; to feel shame because I cannot take care of my family.

I’ve never thrown a trashcan. But I’ve wished I could, countless times.

I can’t pretend that I know what it feels like to be black in a racist culture that rewards whiteness and punishes blackness. But maybe, just maybe, I can empathize the tiniest bit because of my own experiences.

I’ve always felt empathy for those who have been hurt; who have felt powerless or defenseless in the face of overwhelming power. Maybe that’s why injustice fills me with rage. Maybe that’s why I yearn to add my voice to that of the oppressed whose cause isn’t specifically my own.

But the cause of the oppressed should be that of humanity, of which we are all members. This is the brilliance, relevance, and power of Do the Right Thing. It takes the cause of the minority and communicates it to the whole with unflinching honesty.

*****

Da Mayor: Always do the right thing.

Mookie: That’s it?

Da Mayor: That’s it.

Mookie: I got it, I’m gone.