Calvin & Hobbes Documentary Draws Great Pleasure

DIRECTED BY JOEL ALLEN SCHROEDER/2013

Throughout the 20th century, every generation had at least one great work of art with which to stake their claim in the social history: It Happened One Night, The Catcher in the Rye, The Graduate, Dark Side of the Moon, The Breakfast Club, Nevermind. This was our legacy, our voice for the ages; with pop culture as the platform for our collective experience, we turned to literature and music and film to serve as the lens through which to define ourselves, to clarify our own struggles, and to identify our place in the greater whole.

Throughout the 20th century, every generation had at least one great work of art with which to stake their claim in the social history: It Happened One Night, The Catcher in the Rye, The Graduate, Dark Side of the Moon, The Breakfast Club, Nevermind. This was our legacy, our voice for the ages; with pop culture as the platform for our collective experience, we turned to literature and music and film to serve as the lens through which to define ourselves, to clarify our own struggles, and to identify our place in the greater whole.

One of the most maligned venues for this shared venture was the comic strip. Harkening back to the turn of the century, comics provided a light, breezy respite from the social ills filling the papers that housed them, affording readers a sanctuary of joy and humor amidst of their morning routine. More often than not, the funny pages were dismissed as kids’ stuff, a mere trifle designed to fill space; however, as the decades passed, the form grew more sophisticated, resulting in such timeless works as Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, Walt Kelly’s Pogo, and Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. The last quarter of the century marked the peak of the funnies’ relevance and popularity, giving rise to such strips as Berkeley Breathed’s Bloom County, Gary Larson’s The Far Side, and, particularly, Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes.

Among a wide swath of the population, comprised of both casual readers and diehard fans, Calvin and Hobbes is routinely cited as the greatest comic strip ever made, the pinnacle of the form, a work of art that continues to enthrall and entertain. But to those who came of age in the late ’80s and ’90s, it is something much more: a cherished artifact of their youth, an ode to friendship and fun and mischief and imagination, a guide for how to make sense of a chaotic world, a handbook for living life to the fullest in the face of adversity and pain. Imbued with deep philosophical musings, yet universal enough to appeal to both the young and the old, its legacy and impact are profound.

Director Joel Allen Schroeder

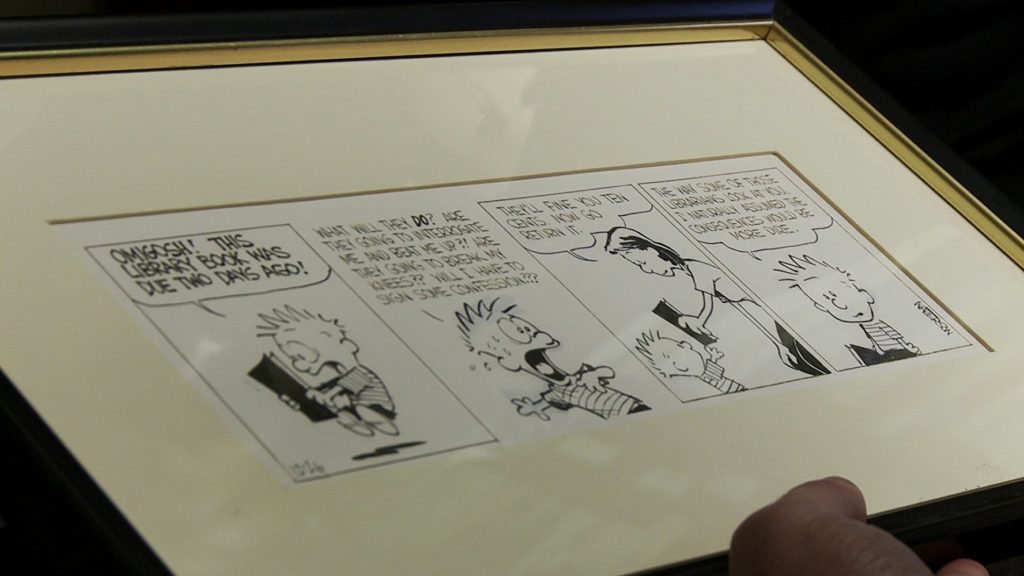

Joel Allen Schroeder’s Dear Mr. Watterson conveys the effects of the strip on both a personal and societal level. Serving as a representative for a generation reared on the adventures of a boy and his tiger, Schroeder travels to Watterson’s hometown of Chagrin Falls, OH, in search of a first-hand connection to the famously reclusive artist. What he finds is a world much like Calvin’s own, filled with the quiet neighborhoods and rich, rolling forests that inspired Calvin’s flights of fancy. Soliciting help from local Watterson friends and fans—in particular, a library packed with archival treasures—Schroeder dissects the ways in which a single strip served as a flashpoint for the whole industry.

It is here that Schroeder delivers his real coup: obtaining interviews from Watterson’s own contemporaries in the field, including the aforementioned Berkeley Breathed, FoxTrot‘s Bill Amend, Pearls Before Swine‘s Stephan Pastis, Non Sequitur‘s Wiley Miller, Bizarro‘s Dan Piraro, and Jean Schulz, widow of the late Charles Schulz. It is through their perspective that the revolutionary nature of the strip is fully revealed, as each testifies to both the singular genius of Watterson’s work and his notorious refusal to compromise his artistic integrity by merchandising his characters. The latter proved a major sticking point throughout Calvin and Hobbes‘s ten-year run, positioning Watterson as the idealistic counterpoint to such artists as Schulz and Garfield‘s Jim Davis, who marketed their creations with tireless fervor. Pastis, in particular, delivers a heartfelt and stirring testimony of the countless compromises that result from ceding control of one’s work to distributors who care only about the bottom line. Seen in this light, Watterson reads as an artist in love with his craft, who knew exactly how he wanted his creation to be presented and received, and who achieved his goal with the utmost perfection and class.

The ultimate triumph of Dear Mr. Watterson lies in its providing a requiem for a bygone era, a time in which a single artist could reach millions of people at once, when all walks of life could unite under the banner of a common shared experience. The slow death of print media, coupled with the Internet’s having forever splintered our collective focus, means that no one work will likely ever unite us in the same way again. Calvin and Hobbes was the last of its kind, arriving and departing at exactly the right time, serving as both the standard bearer and the pallbearer of pop culture within the funny pages and beyond. For those of us who remember, it’s still a magical world.