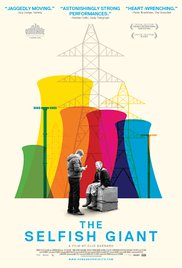

Trampled Underfoot In England

DIRECTED BY CLIO BARNARD/2013

Every afternoon, as they were coming from school, the children used to go and play in the Giant’s garden.

Every afternoon, as they were coming from school, the children used to go and play in the Giant’s garden.

— Opening lines of Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant

Clio Barnard’s The Selfish Giant bears little resemblance to the Oscar Wilde short story from which it takes its name. Wilde’s yarn is about an uncaring giant who takes umbrage at innocent children playing in his garden. Barnard’s version is about two truants salvaging/stealing copper wire for a shady scrap dealer. It’s no use trying to align the two stories to see where their symbols might line up. Perhaps society is the giant? Perhaps it’s the garden? At the very least, they agree in their lyrical beauty and abruptness. The Selfish Giant is a gut-wrenching look at the joys and pains of the most vulnerable members of modern society.

Arbor (Conner Chapman) is a turbulent, slight-framed kid waiting out his youth like a prison sentence in Bradford, England. His only friend, the heftier Swifty (Shaun Thomas), reluctantly, but loyally, plays along with his schemes. They are outcasts at a school that has no patience for them, and they are burdens to the abusive families that don’t know what to do with them.

Early on Swifty comes home to witness his father (not-so-ironically named “Price Drop”) selling the last couch in the house so that he can ostensibly sort out the electricity bill—though you imagine Price Drop will use the cash to square less noble accounts. Arbor and Swifty, being completely unsupported by any social framework put around them, try to look past the sullen backdrops of their dead town, and instead scheme to break free of the urgency of electricity bills and school exams. Their bleak circumstances lead them into the employ of Kitten (Sean Gilder), a scrap yard owner who has no scruples about receiving stolen merchandise. The kids resourcefully amass a healthy amount of scrap, with Arbor swiping copper wire like he’s feeding an addiction. Swifty is more enamored with Kitten’s prize horses, used for impromptu road race competitions. His patience and good nature help balance out Arbor’s hyperactive restlessness.

Arbor and Swifty have scrap metal, horses and each other.

The Selfish Giant contains a vision of England that we don’t often see in the states. Sure there’s the dingy Britain you can catch a glimpse of in Harry Brown or Snatch. But even those movies make it seem like a dystopia I could vacation in. In The Selfish Giant, however, cinematographer Mike Eley stares unapologetically into the gaping maw of a blighted Northern England. Ominous cooling towers preside over foggy moors; railroad tracks cross every which way, so that no matter where you are, you are always on the wrong side of the tracks. So otherworldly is this place, that towards the beginning of the film I had a hard time figuring out whether or not it was set in a symbolic, parallel-universe, a la Beasts of the Southern Wild.

Yet, for all of its surreal qualities—how many films feature illegal horse races?—The Selfish Giant is grounded in the realism of the friendship of its protagonists, Arbor and Swifty. Conner Chapman and Shaun Thomas, both non-actors, carry the movie almost completely. I was reminded of Ale and his sister Izzy from the film Chop Shop. Children forced to become adults. Their energy and optimism swinging like tack hammers on the Great Wall of societal failure. Arbor’s determination and Swifty’s compassion would flourish like blossoms if they were in less barren lands.

But as it is, they can only hope to attain the demands of the urgent, and not the fantasies of the ideal. They are pikeys in that they are always on the pike (road); they are transient, impermanent, both geographically and in the grand scheme of things. Who will remember them? Who speaks for them? The writer of Proverbs 31, the mother of a king, advises her son:

Open your mouth for the mute,

for the cause of all the sons of the vanishing.

Open your mouth, judge righteously

and plead the case of the poor and needy. (Prov. 31:8-9, my translation)

Clio Barnard does not attempt to lecture the viewer, or shame them into action, which social realist films can sometimes do. There is no title card imploring us to support a particular cause. Rather, she tells us the story of the sons of the vanishing, attempting to erase some of the ugliness of the world with the beauty of friendship.