Calm Like A Bomb

DIRECTED BY HAIFAA AL-MANSOUR/ARABIC/2013 (USA release)

More has been said about the buzz surrounding Wadjda than about the story within it. It is the first feature film completely shot in Saudi Arabia—a country that has no movie theaters, much less a movie industry—and the first Saudi film directed by a woman, Haifaa Al-Mansour. The logistics of having a woman direct a movie in Saudi Arabia is deserving of a documentary in itself. As if that wasn’t scandalous enough for hyper-conservative Saudi society, the movie is in many ways about the modern-day institutionalized oppression of women in that country. But that’s the buzz surrounding Wadjda. The story within it? It’s about a little girl who wants to buy a bicycle.

More has been said about the buzz surrounding Wadjda than about the story within it. It is the first feature film completely shot in Saudi Arabia—a country that has no movie theaters, much less a movie industry—and the first Saudi film directed by a woman, Haifaa Al-Mansour. The logistics of having a woman direct a movie in Saudi Arabia is deserving of a documentary in itself. As if that wasn’t scandalous enough for hyper-conservative Saudi society, the movie is in many ways about the modern-day institutionalized oppression of women in that country. But that’s the buzz surrounding Wadjda. The story within it? It’s about a little girl who wants to buy a bicycle.

Wadjda (Waad Mohammed) is a pair of purple-laced Converse All-Stars hiding underneath a black abaya. She is a loud rock song right before dinner time. She is a smart mouth response belying a pair of doe eyes. Wadjda is a universe of energy filtered into a five foot frame. She is also an 11-year old girl in Saudi Arabia who wants a bicycle, badly. Not just any bicycle. No living breathing kid wants just any bicycle. She wants the tasseled, Saudi-green beauty that just came into the corner shop, seemingly transported there by angels. Wadjda’s mother (Reem Abdullah) warns her quixotic daughter of two very real hurdles to bike ownership. Even if Wadjda were to sell a backpackful of her popular handcrafted friendship bracelets, she would still be far too short of the 800 riyals sticker price.

“Wadjda” never feels heady or heavy-handed, though, as films by film lovers sometimes become. At its core it is defiant, but it is careful never to demonize any particular element of Saudi culture.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly to everyone except her, girls don’t ride bicycles in Saudi Arabia. To clarify, it is illegal for a woman to ride a bicycle in Saudi Arabia (note: the laws on this have since changed somewhat in the last year). Undaunted, Wadjda, a precocious hustler, crafts a few schemes to overcome at least her monetary barriers. She enters a school-wide Koran reading competition in hopes of winning the 1000 riyal grand prize and perhaps winning over the totalitarian headmistress who thinks she is nothing but trouble. Through this coming of age, slice of life story we are made privy to the nuances of day to day living in a patriarchal society that seems to perpetuate itself only through the invisible oppression that comes from unquestioned custom.

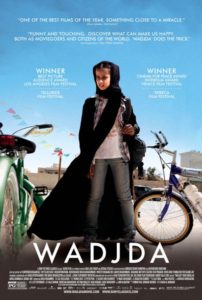

Wadjda in subtly superheroic garb.

Haifaa Al-Mansour has created a film that exists on the corner of Protest and Feel Good. She grew up on movies—a feat in itself in a country where women weren’t even allowed to rent movies—and her love for the cinema is apparent in the manifold references and nods throughout the film. In an NPR interview, Al-Mansour herself admits to the influence of The Bicycle Thief, and there are notes of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in her approach to institutionalized oppression. Wadjda’s name is most likely a reference to Andrzej Wajda, director Man of Marble, a film about a 1970s Polish woman overcoming opposition to produce a documentary critical of Communist rule.

Wadjda never feels heady or heavy-handed, though, as films by film lovers sometimes become. At its core it is defiant, but it is careful never to demonize any particular element of Saudi culture. It could have easily become a litany of criticism on the Quran, or Middle-Eastern politics, or men, or women who are the gatekeepers of much of the particular Muslim traditions that Westerners may find abhorrent. But it treats the Quran with great reverence, politics with proper acknowledgement, men are sometimes good, sometimes bad, and women are sometimes traditional, sometimes not as much. Almost as if life is actually a complex set of systems and not a collection of sound bytes. Wadjda could have taken the low road of loud shocking melodrama in order to prove a self-righteous point, and it still would have received some regard. Instead it takes the highest road possible: hopefulness. It tells the story of a lively young girl keeping her soul from being swept away by the whims of circumstance. Wadjda’s infectious spirit of optimism makes her incapable of being a victim and frees her—and the film—from the need to victimize others.

Al-Mansour had to direct actors from inside a van via walkie-talkie because of Saudi laws that prevent unrelated men and women from being seen together in public.

Will Haifaa Al-Mansour’s movie ever resonate with her own people? That remains to be seen. Al-Mansour has said that she was introduced to the outside world through beautiful cinema. She laments that so many of her Saudi peers have not had that opportunity, to see beauty, to experience life. It is not necessarily that they’ve been lied to, just that they haven’t experienced the beautiful fullness of truth. Only in a world deprived of beauty can the truth remain hidden. Filmmakers are the new preachers, they are the sowers of ideas, both good and bad. The most captivating among them enrapture our senses and conquer our hearts. Jean-Luc Godard once said, “Cinema is truth at 24 frames per second.” If there is something that the cinema has taught me, it’s that for better or worse, those who make the beauty get to tell the truth.

Wadjda is beautiful. Wadjda is true.