Once Upon A Time, In A Far Away Land…

An apology upfront for that oh so predictable opening line. Some might even so far as to call it “tired”. But really, I’m not actually sorry. This is, after all, the fairy tale movie themed edition of our regular “Film Admissions” column, and what self-respecting fairy tale doesn’t, in some permutation, open that way? Even as notions of what does and doesn’t constitute being a “fairy tale” evolve, morph, and lazily expand, those classic opening words remain a genuine signifier.

An apology upfront for that oh so predictable opening line. Some might even so far as to call it “tired”. But really, I’m not actually sorry. This is, after all, the fairy tale movie themed edition of our regular “Film Admissions” column, and what self-respecting fairy tale doesn’t, in some permutation, open that way? Even as notions of what does and doesn’t constitute being a “fairy tale” evolve, morph, and lazily expand, those classic opening words remain a genuine signifier.

For over 100 years, such films have proven irresistible to audiences of all ages, filmmakers of all nationalities, and movie studios the world over.

But, the only words we’re actually here for are the ones our contributors have provided. With movies, it’s not words but images that come first and foremost. And although fairy tales themselves have solid roots in the written word, its the pictures they plant in our heads that truly resonate. Movies about fairy tales bear the uncanny ability to actualize this phenomenon, projecting ambitious filmmakers’ best interpretations of these dark, wondrous, moralizing stories which hail from the unspoken realms of the psyche. This may sometimes be kids stuff, but its not always so safe. At least, the best ones aren’t. Make no mistake, this is no rebranded rehash of our own Disney Animation Film Admissions.

From the earliest days of the flickering image, to the continuing box office domination of Star Wars (after all, what is “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” other than a space-bound version of “Once upon a time, in a far away land?”), fairy tales have always struck us as naturally cinematic. For over 100 years, such films have proven irresistible to audiences of all ages, filmmakers of all nationalities, and movie studios the world over. (The latter, no doubt, because so many are in the public domain, meaning there’s no author’s licensing fee to pay for the adaptation!)

In our own attempt to grasp what qualifies and what doesn’t, we looked to our own discussions, as well as this handy and sometimes surprising list of fairy tale films, complied by George Wales of GamesRadar.com. Like any good fairy tale, we’ve included incomprehensible visions, classic ventures into dark forests, disembodied grabbing hands, mystical animals, and magic – of the “movie” variety. These are the prime fairy tale movies we somehow hadn’t yet individually seen. Perhaps you too have never seen them, and can join us in our fresh experiences of these dreamland fantasies. We begin with the longest ago of them all, Jean Cocteau’s luminous version of a certain tale as old as time, and work our way to Disney’s recent musical venture Into the Woods…

In our own attempt to grasp what qualifies and what doesn’t, we looked to our own discussions, as well as this handy and sometimes surprising list of fairy tale films, complied by George Wales of GamesRadar.com. Like any good fairy tale, we’ve included incomprehensible visions, classic ventures into dark forests, disembodied grabbing hands, mystical animals, and magic – of the “movie” variety. These are the prime fairy tale movies we somehow hadn’t yet individually seen. Perhaps you too have never seen them, and can join us in our fresh experiences of these dreamland fantasies. We begin with the longest ago of them all, Jean Cocteau’s luminous version of a certain tale as old as time, and work our way to Disney’s recent musical venture Into the Woods…

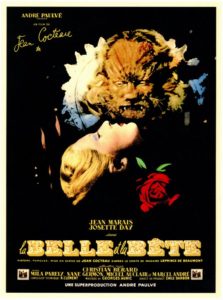

Beauty and the Beast

(1946, DisCina, dir. Jean Cocteau)

by Robert Hornak

I’m no doubt late to this bright idea, but it never struck me till I finally saw Cocteau’s film how much of a greatest-hits the story is of Dracula (hidden, mist-shrouded castle lair), The Wolf Man (restless, hirsute consumer of wild animals), and The Phantom of the Opera (desperate, lovelorn captor of damsels), an observation that probably reveals my much stronger impulse for straight-up classic horror movies than fairy tales. Outside of the spoofy takes on this type of story offered up everywhere from Rocky & Bullwinkle’s “Fractured Fairy Tales” to DreamWorks’ Shrek series, I’ve never been especially drawn to the genre. My knee-jerk judgment is to banish them to the same didactically-driven, nuance-deprived category as fables, allegories, even parables. “Lesser” stories told to teach a lesson, prove a point, or reveal a tick of human nature, only cloaked in the darker garb of black forests, poison apples, and evil animal-men.

I’m no doubt late to this bright idea, but it never struck me till I finally saw Cocteau’s film how much of a greatest-hits the story is of Dracula (hidden, mist-shrouded castle lair), The Wolf Man (restless, hirsute consumer of wild animals), and The Phantom of the Opera (desperate, lovelorn captor of damsels), an observation that probably reveals my much stronger impulse for straight-up classic horror movies than fairy tales. Outside of the spoofy takes on this type of story offered up everywhere from Rocky & Bullwinkle’s “Fractured Fairy Tales” to DreamWorks’ Shrek series, I’ve never been especially drawn to the genre. My knee-jerk judgment is to banish them to the same didactically-driven, nuance-deprived category as fables, allegories, even parables. “Lesser” stories told to teach a lesson, prove a point, or reveal a tick of human nature, only cloaked in the darker garb of black forests, poison apples, and evil animal-men.

Thus my long delay in seeing this beloved classic of world cinema. I can’t say that I didn’t know what to expect. I’d read co-ZekeFilm writer Justin Mory’s take on the film’s history and style last year (but purposefully avoided re-reading before this first viewing), and had a general sense of the story from the Disney version. But you can’t fully expect what you’ll get when you watch this beautiful film. The relatively straightforward presentation of Belle’s world, defined as it is by the fairy tale litany of oppressive sisters, aggressive suitor, and a loving but ailing father who draws health from her bottomless well of love and kindness, gives way to the dream-like house of heartbreak that is the Beast’s seemingly permanent exile, where wind whips warmly-lit roses into a frenzy, living faces judge silently from inert statues, and a full staff of disembodied hands hold lamps and serve drinks to mystified guests. When father stumbles on the castle and dares to pick a rose for Belle, the Beast emerges, befanged, leonine, in his noble-if-dandy regalia of fanciful cuffs, collars and medallions, his fully-vexed sarcasm in tow, and grants father a short reprieve home to tie up loose ends before returning to the castle forever, during which time loving daughter Belle steals away in his stead, and slowly redirects her heart of love from the father to the lonely creature. From this point, Belle’s object of deepening affection becomes ours, as the Beast’s plaintive whisper-growls — he’s a doleful werewolf Hamlet — seem so close to the screen that it’s like you hear it in your own ear, and his wide and feeling eyes project pain and loneliness from such a deep and wounded place. Frankly, it’s tough to resist hugging your TV.

The shifting of Belle’s pure goodness from home to castle gives enough Freudian oomph to the movie, it could make you reasonably expect the Beast to turn back into her father at the end. But whoever he’s restored to in those final moments, it will always play as a loss. The Beast, as the Beast, in all his poetic brokenness, has won our hearts, and we feel cheated when he’s obliterated by the happy ending. We’re left to collectively repeat Marlene Dietrich’s famous plea to Cocteau upon seeing the end of his film: “Where is my beautiful Beast?”

The Fearless Vampire Killers

(1967, Cadre Films, dir. Roman Polanski)

by Paul Hibbard

The Fearless Vampire Killers, also subtitled Pardon Me, but your Teeth are in My Neck or Dance of the Vampires, is a completely missed film (by me at least, when I was on a major Polanski tear 10 years ago) and many others in this country. And in a way, that may be a good thing. Not that it’s bad, per se, but is such a left turn from his other 60’s films including Knife in the Water, Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby.

The Fearless Vampire Killers, also subtitled Pardon Me, but your Teeth are in My Neck or Dance of the Vampires, is a completely missed film (by me at least, when I was on a major Polanski tear 10 years ago) and many others in this country. And in a way, that may be a good thing. Not that it’s bad, per se, but is such a left turn from his other 60’s films including Knife in the Water, Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby.

In the story, a goofy professor (Jack MacGowran) and his aloof assistant (Polanki himself) hunt down a family of vampires in Transylvania. From there, goofy humor and very un-Polanski material happens (or at least how I have been trained to view Polanski).

This movie is not recommended, per se. But it is important to view it in context. It’s not going to have anywhere near the gut punch that Knife in the Water or Rosemary’s Baby had. And a lot of the European humor and nuances do not seem to transfer over to an American audience as well. Which is possibly why this is incredibly under-seen in the States.

But if you can go in with that mindset, you will discover a side of the director you may not have known existed. And a very beautiful looking film that will make you smile, if not laugh at times. And Sharon Tate. Wow. Sharon Tate.

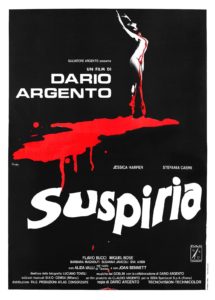

Suspiria

(1977, Seda Spettacoli, dir. Dario Argento)

by Sharon Autenrieth

Not only was this my first viewing of Suspiria, it was my first viewing of a Dario Argento movie. This lurid, beautiful, dreamlike movie was not what I was expecting. Fairy tale? Yes, in the most grim of the Grimms’ style. Suspiria follows a young American, Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), as she travels to Germany to attend a ballet academy, only to discover that dark and horrible thinks are afoot in her new home. There are bloody deaths along the way, but Suspiria is nothing like the American slasher films of the period. It’s so much more surreal and disorienting, so overwhelming both in sound and visuals that it’s an immersive experience. As soon as Suzy steps out of the airport near the beginning of the film (after a jarring and bloody opening scene involving another dance student) she steps into a nightmare. The vision of the a young women in red fleeing through the Black Forest is the film’s first explicitly fairy tale touch – but the Tans Academy is much scarier than any dark forest could ever be.

Not only was this my first viewing of Suspiria, it was my first viewing of a Dario Argento movie. This lurid, beautiful, dreamlike movie was not what I was expecting. Fairy tale? Yes, in the most grim of the Grimms’ style. Suspiria follows a young American, Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), as she travels to Germany to attend a ballet academy, only to discover that dark and horrible thinks are afoot in her new home. There are bloody deaths along the way, but Suspiria is nothing like the American slasher films of the period. It’s so much more surreal and disorienting, so overwhelming both in sound and visuals that it’s an immersive experience. As soon as Suzy steps out of the airport near the beginning of the film (after a jarring and bloody opening scene involving another dance student) she steps into a nightmare. The vision of the a young women in red fleeing through the Black Forest is the film’s first explicitly fairy tale touch – but the Tans Academy is much scarier than any dark forest could ever be.

The human characters in Suspiria are bad enough: the employees at the Academy are creepy or freakish – every last one of them. Of special note are Miss Tanner (Allida Valli) who smiles as if she’s about to to tear you apart with her teeth, and Joan Bennett as Madame Blanc, the head of the academy. At least she’s the head while the directress is away. But who is that directress, and is she actually away at all??? (By the way, both Valli and Bennett had fascinating careers pre-Suspiria. Look them up.) Harper herself is solid as the wide eyed waif trying to unravel the mystery of the Tans Academy. She is so slender, so fragile looking – she should at least be safe from any witch’s oven in her candy colored surroundings.

I don’t want to describe Suspiria because it seems indescribable. The Academy’s décor is so bizarrely ornate – is it Art Deco? Is it Baroque? Is it the way you’d do interior design while high on opium? The lighting changes the color of the scenes in ways that make no senses (except, again, in the way that things make sense in your dreams). And the music – lilting music box melodies mixed with pulsing drums, breathy voices, shrieks, pounding synth chords – there is a lot going on, and it makes it hard to think. But this isn’t a movie that you really need to think about, so much as you need to receive it, experience it, pass through it in the same way that Suzy passes through the blood red corridors to the heart of the academy’s dark secret.

Legend

(1985, Universal Pictures, dir. Ridley Scott, US Theatrical Cut, 89 minutes, with Tangerine Dream soundtrack)

by David Strugar

I remember being mildly disappointed by the first Lord of the Rings movie (stay with me now), because as grand as it aspired to be, it also felt exactly like every other fantasy movie or video game that had been inspired by Frodo’s adventures in the decades since the book was published. Bigger budget, more intricate and elaborate art direction, better actors, but often the same well-worn ground that had been traveled by Tolkien enthusiasts and wannabes for years.

I remember being mildly disappointed by the first Lord of the Rings movie (stay with me now), because as grand as it aspired to be, it also felt exactly like every other fantasy movie or video game that had been inspired by Frodo’s adventures in the decades since the book was published. Bigger budget, more intricate and elaborate art direction, better actors, but often the same well-worn ground that had been traveled by Tolkien enthusiasts and wannabes for years.

Ridley Scott wanted to tell a classic fairy story with LEGEND, and gave writer William Hjortsberg (I spelled that correctly on the first try, thank-you-very-much) the simple instructions to write him something with unicorns and a villain named Darkness. From there, the story touches on themes of light vs. dark, innocence vs. seduction, and…not much else. In constructing an archetypal fairy tale, Scott gives us all the basic touchstones of the genre, presented with truly fantastic makeup, effects work, and cinematography, but doesn’t explore the themes much farther than your average bedtime story.

As the heroes try to destroy him, Tim Curry’s prosthetic masterpiece of a villain gloats that there is no light without the darkness, and that it’s foolish for them to think he’ll ever be defeated—all while he himself is trying to put an end to the light by killing the unicorns. It’s the low-hanging philosophical fruit that many a fantasy story reaches for, but the film doesn’t engage with the idea beyond the one line of dialogue. In the moment, I think we’re supposed to feel like it’s some dramatic revelation.

Too, the narrative itself stumbles along with what I’d like to call dream-logic, if I thought that’s what Scott was going for. It feels more like a lack of specific choices, going for the most easily recognizable fairy tale tropes and sewing them together into an hour-and-a-half of events that take place in order to hit certain beats. This works a bit better if you have the snazzy songs of a Disney movie or the snappy dialogue of The Princess Bride, but not so much here, where even the famed charisma of star Tom Cruise seems to be MIA.

Even the title is generic, shortened from the slightly longer but just as meaningless Legend of Darkness from earlier drafts of the script.

To be fair, the original UK release ran several minutes longer and featured a less-trippy score by Jerry Goldsmith than the one Universal commissioned from Tangerine Dream for the US version—it’s also pricier to get one’s hands on. I’d like to revisit it at some point, once my memory has cleared of the one I saw.

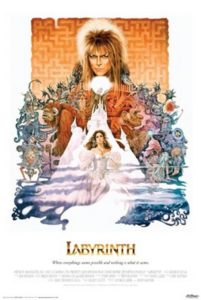

Labyrinth

(1986, The Jim Henson Company, dir. Jim Henson)

by Jim Tudor

David Bowie. Jim Henson. George Lucas. All are indisputable artistic idols of mine. How on Earth, then, can it be that I’ve never see their fondly remembered 1986 fantasy collaboration, Labyrinth?? Factor in young Jennifer Connolly, whom everyone likes, in her first major starring role and a sly, imaginative screenplay by Terry Jones of Monty Python and “Erik the Viking” fame, this blind spot becomes all the more glaring.

David Bowie. Jim Henson. George Lucas. All are indisputable artistic idols of mine. How on Earth, then, can it be that I’ve never see their fondly remembered 1986 fantasy collaboration, Labyrinth?? Factor in young Jennifer Connolly, whom everyone likes, in her first major starring role and a sly, imaginative screenplay by Terry Jones of Monty Python and “Erik the Viking” fame, this blind spot becomes all the more glaring.

Known primarily (and rightfully) for The Muppets, It should be no surprise that Labyrinth is a gloriously puppet-centric film. All kinds of puppets are utilized, from standard hand puppets to full body suits to less conventional types such as marionettes, rod puppets, and good old fashioned contorted hands. Henson channels his enthusiasm for the art in all its permutations into a darkly adventurous cinema. Though he himself is synonymous with colorful children’s programming, it’s telling that two of Henson’s three big screen directorial outings (this and 1982’s even more ominous The Dark Crystal) fall squarely under the header of “kiddie horror”, a movie niche that thrived via fairy tale fantasy in the 1980s.

Opening with slow panning shots of revered modern fairy books such as “Where the Wild Things Are”, “The Wizard of Oz” and “Alice in Wonderland”, Labyrinth is refreshingly unafraid to put its cards on the table in regard to its being a largely referential work. For good measure, in the closing credits, Henson gives special acknowledgment to the work of Maurice Sendak. Like it’s one-year-older contemporary, Rob Reiner’s The Princess Bride, it is a movie that cleverly and buoyantly builds upon its well known genre predecessors.

And then there’s David Bowie. His turn a Jareth the Goblin King is something to behold, a fully owned musical Lucifer. It’s tempting to wonder how much of his perfection here is sheer presence versus acting ability (which he possesses), but does it matter? This being his most mainstream and most visibly accessible lead role, it’s little wonder then that it’s experienced a significant revival following his recent death.

Yet, now, as I watch Labyrinth for the first time, it’s own sphere of influence is obvious. One needs to see only the first act, replete with a white owl, characters running through walls, and even the (mistaken) name “Hogwart” to wonder how many times J.K. Rowling saw this film in her more formative years. This year, Labyrinth will get a 4K blu-ray release, and continues to draw new audiences into its maze of wonders. I consider myself fortunate to be among them. It’s been too long coming.

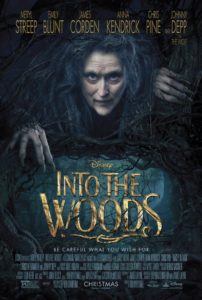

Into the Woods

(2014, Walt Disney Pictures, dir. Rob Marshall)

by Taylor Blake

A musical? With fairy tales? And a stellar cast? Make it one of my three wishes!

A musical? With fairy tales? And a stellar cast? Make it one of my three wishes!

When I first heard about Disney’s film adaption of Into the Woods, it sounded just like the kind of movie I’d enjoy. After its release, though, friends’ word-of-mouth reviews were mixed. Several said it was dark, at least one said it dragged, and almost all said it wasn’t what they expected.

That meh evaluation and a busy holiday schedule pushed it lower and lower on my list, so I didn’t even watch it during my normal Oscar nominee binge in the month before the ceremony. Now that I’ve seen it, I can understand the tepid response, even if I don’t share it. Fairy tales garner expectations of fluffy feelings and happy endings, and intertwining the characters Valentine’s Day-style seems like it would magnify that exponentially. (Think TV’s Once Upon a Time.)

Into the Woods is not that at all, but a deconstruction of those assumptions. None of the characters are particularly heroic for most of the movie, flirting with gray areas and justifying selfish means with admirable ends. They sing of the differences between good and bad and nice people, and one mentions being in the “wrong story” after an unexpected (and ethically questionable) interaction with another character. This is not a fairy tale with clear-cut answers on who is right and what is wrong. And it is much darker than you would expect—it’s the kind of fairy tale in which even the good (or nice) characters can plunge to their deaths.

With that in mind, Into the Woods is still magical. Its use of setting is clever and meaningful, with the woods representing confusion and murky moral areas. They also provide opportunities to be brave and to mature, and these are moments the cast nails. Before James Corden became our favorite Carpool Karaoke singer, he was a Tony Award-winner. Here, as the Baker, he balances pathos and humor alongside his screen wife Emily Blunt, who is becoming one of my favorite film performers. She’s as convincing and sympathetic as ever, and it turns out she’s a lovely singer as well. Johnny Depp’s Big Bad Wolf cameo is a scene-stealer, and Meryl Streep’s Witch is fantastic, but that’s as surprising as saying the sky is blue (or in this case, her hair).

All of their vocals suit the enchanting, quick-witted music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. The cohesive soundtrack expresses a wide range of voice and personality, from the Witch’s hurt and vindictive “Stay With Me” to the pompous (and actually very funny) “Agony” from the princes.

The only major criticism I’ll lob is about its run time. The perception of time in film and on stage is not the same, which is probably why the pacing feels inconsistent. But is it still worth the long journey Into the Woods? Most definitely.