Sturges Aims For Golden Years, Misses The Mark In The End

DIRECTED BY: PRESTON STURGES/1949

STREET DATE: NOVEMBER 1, 2016/KINO LORBER

Preston Sturges rose out of screenwriting fame in the ’30s, wrote and directed some brilliant comedies in the early ’40s, arguably among the greatest comedies ever made, and then, after a falling out with Paramount, for whom he was an ever-loving goldmine, seemed to diminish, making a few more films of little notoriety before finally disappearing and leaving the earth nearly forgotten. Today, outside of reverent film circles, he’s not generally name-dropped beyond conversations that don’t also include the Coen Brothers. His slide into cinematic inactivity and finally a kind of unseemly obscurity is forgotten, though, with a single rewatch of any of his Paramount films: the spirit of abandon, speed, life, and charm sweeps you into its current until, in the end, you don’t care so much about characters and plot, per se, as a continuation of the giddy tempo and rhythm. His gift was as “an instinctive impresario of graceful accelerations” (critic Manny Farber) by creating a manic pace that was only barely reigned in by the structural rigidity of his plots. Simply, his early directed movies are where you go, along with a few Howard Hawks titles, to demonstrate the epitome of intelligence and style in ’40s American comedy.

Preston Sturges rose out of screenwriting fame in the ’30s, wrote and directed some brilliant comedies in the early ’40s, arguably among the greatest comedies ever made, and then, after a falling out with Paramount, for whom he was an ever-loving goldmine, seemed to diminish, making a few more films of little notoriety before finally disappearing and leaving the earth nearly forgotten. Today, outside of reverent film circles, he’s not generally name-dropped beyond conversations that don’t also include the Coen Brothers. His slide into cinematic inactivity and finally a kind of unseemly obscurity is forgotten, though, with a single rewatch of any of his Paramount films: the spirit of abandon, speed, life, and charm sweeps you into its current until, in the end, you don’t care so much about characters and plot, per se, as a continuation of the giddy tempo and rhythm. His gift was as “an instinctive impresario of graceful accelerations” (critic Manny Farber) by creating a manic pace that was only barely reigned in by the structural rigidity of his plots. Simply, his early directed movies are where you go, along with a few Howard Hawks titles, to demonstrate the epitome of intelligence and style in ’40s American comedy.

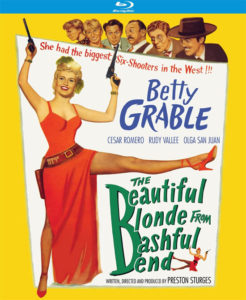

Sturges has a way of rolling around inside a comic idea for an entire movie, letting his freewheeling sensibility be the picture’s engine, imbuing the proceedings with a verve that’s irrespective of the plot proper, yet there’s nearly always some thoughtful bread baked into the circuses: The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tweaks small town mores, Hail the Conquering Hero reveals the hollowness of bestowed glory, Sullivan’s Travels begrudges an apotheosis of the common man, and so on. But by the late ’40s, struggling outside his comfort zone at Paramount, the seams began to show, so that by decade’s end his western comedy The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend – starting with its cumbersome title – is essentially all bluster, no bread, a 77-minute straight shot of cantankerous verbiage and plot-folding double-dealings and mistaken identities whose high-octane plotting keeps you busy – but never really makes you laugh. Betty Grable is the popular saloon-singing, gun-slinging savant Winifred “Freddie” Jones, who takes aim at her cheating guy pal (Cesar Romero) but hits a judge (Porter Hall) in the rump instead. So she gets out of Dodge and takes up in a neighboring town under the guise of the new school teacher, where much fun is milked from the double comic situation of hiding out from justice and pretending to be someone you’re absolutely not, but the continual stacking up of plot contrivances shorts out eventually. The usual Sturges conceits are all there: the baroquely folksy, rapid-fire dialogue, the egalitarian dispensation of screen time to even the most humble of side characters, and the so-be-it attitude toward inescapable consequences (the essential Sturgesian philosophy of “life is nuts but ain’t it fun!”) – but something is missing: heart. You can find it in some version in all his hits. It’s in the earnest hangdog of Eddie Bracken’s Woodrow Truesmith in Conquering Hero, it’s in Fonda’s even more earnest hangdog, and in the more dramatically detailed ups and downs of his and Stanwyck’s trust issues, in The Lady Eve, and it fairly well blankets the entire back half of Sullivan – but in Beautiful Blonde there’s no clear effort to root any of the hyperbolized antics in anything other than Sturges’ stopwatch. It’s an exercise in pulse that emanates from somewhere less vital.

So it’s a busy movie speaking clearly in Sturges’ literate, breakneck hypersnark, and all of it blasted with a truly visceral sting of his first and only use of Technicolor – color which the Blu-ray renders quite vividly. But Sturges’ use of color at all is one of the two great unexpected demerits of the film. As a de facto throwback to pure slapstick of the era he more successfully weaves into his earlier films, the addition of “modern” color, without a commensurate emotional deepening, only highlights the thinness of its plot. Color brings it alive visually, but it distances us psychologically from the intended tone of Sturges’ brand of comedy, something black and white somehow captures more elegantly. As author/film theorist Paul Coates says about color vs black and white comedies, “One feels no compunction at laughing where no red blood can flow.” The other miscalculation is that the movie is a western. There’s something so modern (by ’40s standards and today’s) about Sturges’ spirit, something so perfectly nurtured in him to mock the ridiculous trap of speed and excess and the unending unspooling of glass and steel that is the modern world, that shifting the m.o. into that earlier time feels intrinsically wasteful. This is not a terrible movie – in fact, it has many entertaining moments. Sadly, though, it’s the kind of movie that if you don’t know Sturges, you might say, “This is different!” – but if you do know Sturges, you feel in your guts it’s just not up to his high, early ’40s standard.

The images in this review are not representative of the actual Blu-ray’s image quality, and are included only to represent the film itself.