The Un-Romanticized Era of Depression Anti-Nostalgia

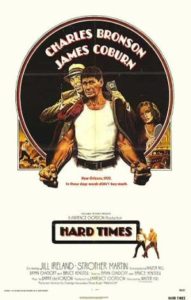

DIRECTOR: Walter Hill/1975

A freight train comes whistling ’round the bend carrying, along with its cargo, a solitary traveler. Wearing a flat cap and dressed in plain workmen’s clothes, the grizzled, lined features of every man standing in a bread line on every city street corner across the country looks out from the open door of his “private” boxcar to regard the country crossroads of Southern America. Whizzing by a flatbed truck, the man locks eyes momentarily with two kids standing in the back, their “pa” (presumably) a shadowy figure in the driver’s seat waiting for the train to pass. From the desperate city to the desperate country… or something. Rolling into town around nightfall, the man takes his evening repast at a lunch counter near the town’s center, glancing over his shoulder every now and again to see what’s what in his new surroundings. Watching a group of men congregating near an abandoned factory-looking building across the way, the man turns to the waitress and points at his empty coffee cup. “Third refill costs a nickel,” says the waitress. The man holds up a nickel and places it on the counter. “Tip.” Adjusting his cap, five cents lighter and six remaining dollars to his name, the man crosses the street to join what promises to be the center of attraction.

A freight train comes whistling ’round the bend carrying, along with its cargo, a solitary traveler. Wearing a flat cap and dressed in plain workmen’s clothes, the grizzled, lined features of every man standing in a bread line on every city street corner across the country looks out from the open door of his “private” boxcar to regard the country crossroads of Southern America. Whizzing by a flatbed truck, the man locks eyes momentarily with two kids standing in the back, their “pa” (presumably) a shadowy figure in the driver’s seat waiting for the train to pass. From the desperate city to the desperate country… or something. Rolling into town around nightfall, the man takes his evening repast at a lunch counter near the town’s center, glancing over his shoulder every now and again to see what’s what in his new surroundings. Watching a group of men congregating near an abandoned factory-looking building across the way, the man turns to the waitress and points at his empty coffee cup. “Third refill costs a nickel,” says the waitress. The man holds up a nickel and places it on the counter. “Tip.” Adjusting his cap, five cents lighter and six remaining dollars to his name, the man crosses the street to join what promises to be the center of attraction.

The 1970s saw a veritable boom of movies set during the Great Depression. Following the runaway success of Arthur Penn’s masterpiece Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, a brief but by no means complete inventory of Depression-era period pieces – ranging from high-end fare like Chinatown (1974), Thieves Like Us (1974), and Bound For Glory (1976) to action flicks and exploitation fare like Boxcar Bertha (1972), Dillinger (1973), and Big Bad Mama (1974) – reveals an unusual preoccupation with 1930s settings. Beyond the obvious visual appeal of narrow-brimmed hats, waist-clinched dresses, and roadsters with running boards, the period undoubtedly held great historical and thematic appeal for filmmakers of the 1970s as well, nowhere more transparently so than in the famous scene in Bonnie and Clyde where the outlaw Clyde (Warren Beatty) hands a gun to two dispossessed tenant farmers and the pair proceed to shoot out all the windows on a shack the bank had recently foreclosed upon. Making (complicated) protagonists out of (anti-heroic) outlaws and drifters, stories set during the nation’s period of greatest disparity seemed to resonate with movie audiences going home to watch an endless war on TV and waking up to read about the latest abuses of government control in the morning papers. With an eye for stark authenticity, a hallmark of Hollywood’s Second Golden Age of filmmaking, young directors like Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, and Robert Altman made movies that addressed the problems of the present by opening a more realistic window onto the past.

Which brings us to Walter Hill, who, at the time a screenwriter most famous for penning movies like The Getaway (1972) and The Drowning Pool (1975), made his directorial debut with this hardscrabble, Louisiana-set picture taking place in the world of Depression bareknuckled brawling and starring the inestimable Charles Bronson. Hard Times is just that; a spare, stripped-to-the-bone character piece disguised as a fight picture that unassumingly asserts a moral code for life and behavior under the terms of great suffering and deprivation. As reflected in the surprisingly calm, gentle blue eyes of a guy who’s just about to quadruple his initial six dollar-stake by knocking an opponent out with one swift, savage punch, we come to know next to nothing about this Streetfighter (the movie’s original title), either where he comes from or where he’s going; rather, it’s all up there on the screen through three escalating matches with three increasingly dangerous combatants. Actions speak louder than words, and Charles Bronson as Chaney is a man of very few, but those he does say speak volumes: “I knock people down.”

Falling somewhere between action picture and a more serious evocation of its period, Hard Times would, I believe, prove almost impossible to make today. Far as casting is concerned, we have fast-talking James Coburn as Speed, the “smooth operator” who makes the bets and lays the cash down on the barrelhead, and disgraced, opium-addicted “cutman” Poe, played by the incomparable Strother Martin, in immediate support; along with great 70s character actors like Michael McGuire, as gangster-like businessman ‘Chick’ Gandil, and Bruce Glover, as ruthless loanshark Doty; rounding out a deep cast of performers which include real-life stuntmen (Robert Tessier, Nick Dimitri) looking very much the parts of stripped-to-the-waist, bareknuckled-nemeses posing realistic physical threats to Bronson’s tough-weathered character.

As scripted by Hill, there’s a ruthless energy to the bare plot elements which serve to elicit character and theme in the most economical terms possible. Excepting the amusing stream of verbal diarrhea which comes out of the appropriately-named Speed’s mouth, and the withering bon mots effortlessly tossed off by Poe (whose character claims kinship to the “fabled Edgar Allan”), we read more in Chaney’s frequent recourse to half-amused smiles and prolonged periods of silence than entire passages from Tennessee Williams. Economy of style carries over to the production aspect as well, with set-ups, camera angles, and pace-of-editing dictated by character and action, and not the other way round, in the best tradition of Classical Hollywood filmmaking. Finally, the raw energy Hill would later bring toThe Warriors (1979), The Long Riders (1980), and Southern Comfort (1981) is more than evident in the film’s expertly-choreographed fight sequences; when, for example, Chaney himself is knocked down during the film’s final bout with terrifying “hired fist” Street (Dimitri), the bone-crunching impact of two powerful meat hooks across his back is both jolting and visceral.

In all, this lean and tough mid-70s piece of Depression anti-nostalgia gains its power from the style of its telling: simple and direct, like a shot to the jaw. Even the seemingly-perfunctory “romance” with a lonely local woman, Lucy (played by Bronson’s real-life wife and frequent co-star Jill Ireland), is snapped into sharp focus when she breaks it off between them and, angered by his non-response to her having found someone who actually “spends the night”, asks “Is that all you’ve gotta say?” Chaney’s measured silence, again, speaks volumes; a note which is reinforced in the final scene when Speed calls out to a departing Chaney that, after all they’ve been through, “We oughta say something.” Half-smiling again, and turning to walk away, the character who speaks through actions and not words, back on his solitary journey through a desperate country, knows when you need to say something and when you need to shut up. So too does this movie. Showing the terms and price of honor and character rather than just talking about it, Hard Times lives up to its title both in its sharp sense of time and place and its frank and brutal portrait of a man hard enough to live through it.